The Man Behind Clifford: An interview with the Big Red Dog's creator, Norman Bridwell

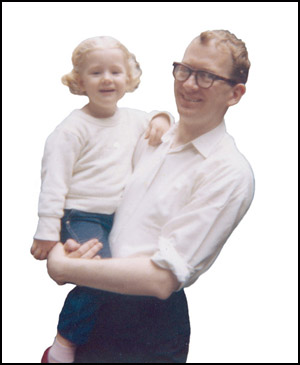

Photo montage: Background from the first Clifford book;

Norman Bridwell by Rich White.

Imagine walking down a street. Exhausted after a workout. Heading toward your car. A dog suddenly appears a quarter of a block ahead. But not just any dog. This one is 66 feet long and 44 feet high.

That’s what happened to me.

That briefest flash of time between seeing Clifford and realizing that I was looking at a parade balloon was magical and delicious. As editor of the Clifford books from 1984 to 2009, I’ve had many magical moments with the big red dog.

I’ve read most of the Clifford books dozens of times. I’ve read some of them hundreds of times. I’ve read them as an editor to prepare them for publication, as a mother to entertain my daughter, and as a Sunday school teacher to spark conversations about pro-social behavior.

The Clifford books are about kindness and good works. They are about making mistakes and being forgiven for them. They are about unconditional love. And they are funny. I still crack up whenever I turn to the page in Clifford the Big Red Dog where a sheepish Clifford holds a car in his mouth, and the text reads: “He runs after cars. He catches some of them.” The artwork is expressive, poignant, and endearing.

The Clifford books are about kindness and good works. They are about making mistakes and being forgiven for them. They are about unconditional love. And they are funny. I still crack up whenever I turn to the page in Clifford the Big Red Dog where a sheepish Clifford holds a car in his mouth, and the text reads: “He runs after cars. He catches some of them.” The artwork is expressive, poignant, and endearing.

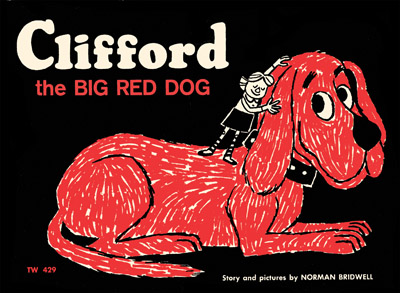

So how big is Clifford? Very big. More than 126 million Clifford books are in print in 13 languages. And an animated Clifford TV series is in its 12th season on PBS Kids. This month marks the 50th anniversary of the first Clifford book, Clifford the Big Red Dog.

And February 15 is the 85th birthday of Clifford’s creator, Norman Bridwell. Kind, modest, and easy-going, Norman, both author and illustrator, is as lovable as his pup. He lives with his wife of 54 years, Norma—that’s right, Norma—in Massachusetts, on Martha’s Vineyard, in a 120-year-old farmhouse. The doors and shutters are painted red in honor of Clifford. Norman and Norma have two grown children (Emily Elizabeth, who appears in the Clifford books, and Tim, who appears in The Witch Next Door) and three grandchildren.

Earlier this year, I spoke to Norman about his remarkable career, his knack for creating pitch-perfect humor for young children, and what makes Clifford (and his creator) tick.

Dog days: Bridwell and his daughter,

Emily Elizabeth, circa 1964.

How would you describe Clifford? He’s a loving dog. He’s very loyal to Emily. And she’s loyal to him. He tries to do the right thing. He has good intentions, but his size makes him clumsy, so he causes damage. And then he’s forgiven. All children would like that—to be forgiven for the mistakes they make.

Do you see any of your own characteristics in him? You know, people have said, “Clifford is a lot like you,” but I’m not really that good. I’m not really that nice.

Well, I would disagree with you, Norman. I worked with you for, like, 25 years and I think you are that nice! That’s kind of you to say. I don’t like to hurt people. I do my best to avoid that. No matter which side you’re on, I’m on it. I really feel I don’t really deserve this. If there’s such a thing as success being handed out to people because they are good and deserving, I don’t really deserve it. I’ve just been very fortunate.

Do you identify with Clifford’s awkwardness when he gets into trouble for being too big? Well, I was… I am pretty clumsy. I’m constantly bumping into things. Or I toss something, and I think it’s going to land on a chair, but it slides off the other side.

I think I’m going to do something clever, and it winds up a disaster. I guess I am like Clifford that way. I was terrible at sports. I was the last one chosen to be on any team. I have many unfond memories of being forced to go out on the basketball court during gym class and trying to shoot a basket and embarrassing everybody.

How did you come to create Clifford? Clifford began as an art sample to show editors. I was hoping I could get a job as an illustrator. I did about 10 paintings. One was of a little girl standing under the chin of a big red dog and holding out her hand to see if it was still raining. I was rejected everywhere I went. One editor, Susan Hirschman, said that my work was too plain. She said, “You may have to write a story, and then if they buy the story, you could do the art. She pointed to the sample of the girl and the dog and said, “Maybe that’s a story.”

How did you come to create Clifford? Clifford began as an art sample to show editors. I was hoping I could get a job as an illustrator. I did about 10 paintings. One was of a little girl standing under the chin of a big red dog and holding out her hand to see if it was still raining. I was rejected everywhere I went. One editor, Susan Hirschman, said that my work was too plain. She said, “You may have to write a story, and then if they buy the story, you could do the art. She pointed to the sample of the girl and the dog and said, “Maybe that’s a story.”

What did you get paid for the book? I got $1,000 for the book and I think $750 to do the art.

The original price of the book was 35 cents. How long did it take you to earn out your advance? Two years.

Three days is a very short time to write a book. Is it easy for you to write? The first one was easy. The others got more difficult. The second Pbook I did was called Zany Zoo. It wasn’t a Clifford book.

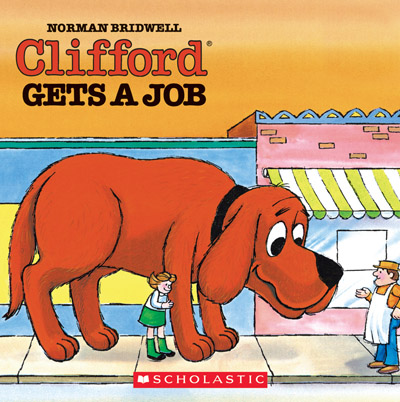

How did the second Clifford book come about? I said to Beatrice, “Would you like to see another one?” And she said, “Yes, if you have an idea, bring it to me, but I’m not going to just take anything.”

I wrote Clifford Gets a Job, and it did well, so I said to Beatrice, “Maybe I should try another one.” And she said, “Well, you know, we’re not running a Norman Bridwell book club.” She said, “You can try some more, but don’t count on my taking them.” The Clifford books did surprisingly well. One day Beatrice called me up and said, “You know, we’ve changed our minds. We do want to do a Norman Bridwell book club.” She said again, “Don’t expect everything to be accepted,” and she stuck to that.

I wrote Clifford Gets a Job, and it did well, so I said to Beatrice, “Maybe I should try another one.” And she said, “Well, you know, we’re not running a Norman Bridwell book club.” She said, “You can try some more, but don’t count on my taking them.” The Clifford books did surprisingly well. One day Beatrice called me up and said, “You know, we’ve changed our minds. We do want to do a Norman Bridwell book club.” She said again, “Don’t expect everything to be accepted,” and she stuck to that. Do you remember any titles that she rejected? You know, it’s been a long time now. They weren’t very memorable... Clifford trying to clean up, trying to protect the environment. That was too preachy. She didn’t like that.

I said to her one time, “Maybe I should be putting a message in these books,” and she said, “You’re not a message person. You just entertain them.” So I did as I was told and just tried to make kids laugh.What’s your process? When I have an idea, I sketch it out in thumbnail sketches—just the action from page to page. When I have the drawings done, I think of the words that go with them. As you know, the words don’t exactly match the picture, which, I think, is funny to the children. The words don’t just describe what is going on, but the kids can figure it out.

What is your studio like? Cluttered. It’s filled with Clifford products Scholastic has given me [such as plush toys, puzzles, games, clothing, and stationery]. I have a desk and a telephone. With an 11-by-14-inch pad and a pencil, I’m in business. I had a studio built kind of late in life, around 12 years ago. I thought I’d jinx myself if I built one before.

What is your studio like? Cluttered. It’s filled with Clifford products Scholastic has given me [such as plush toys, puzzles, games, clothing, and stationery]. I have a desk and a telephone. With an 11-by-14-inch pad and a pencil, I’m in business. I had a studio built kind of late in life, around 12 years ago. I thought I’d jinx myself if I built one before.

How did your kids respond to Clifford while they were growing up? It was just something that Dad did. It wasn’t anything really special. They had other books that they liked much more than Clifford. In fact, on the Internet, my son says his favorite children’s books were by Dr. Seuss. My daughter didn’t realize Clifford was popular until she went to college. I’d given her a Clifford reading rug that she put in her dorm room. The other girls saw it and said, “Oh! Clifford!” When my daughter asked, “How do you know about him?” they said, “Everybody reads Clifford!”

The original Clifford books were black and red, measured eight-by-six inches, and had a landscape orientation. In the ’80s, the books were reformatted to a full-color, eight-by-eight format. Would you talk about that? I guess the original books didn’t show up well in bookstores. When Dick Krinsley joined Scholastic, he converted the books to eight by eight so they could be displayed on a rack.

It amazes me that some people have said, “You know, I liked the early art better.” Some artists object to changes in a book’s original design or format. But you were very cooperative. If I thought my work was beautiful or very artistic, I might feel differently, but I feel that the purpose of my drawings is to get the point of the story across. So I am perfectly willing to have somebody else’s advice on color and format.

Some artists object to changes in a book’s original design or format. But you were very cooperative. If I thought my work was beautiful or very artistic, I might feel differently, but I feel that the purpose of my drawings is to get the point of the story across. So I am perfectly willing to have somebody else’s advice on color and format.

What was it like to grow up in Kokomo, Indiana? It was quiet. It gave me plenty of time to think. I walked to school in the morning, I walked home from school at night, and, all that time, I was making up stories in my mind. Imaginary people. Imaginary places. And then in the evening I’d sit down and draw pictures to go with the stories I thought of during those walks.

I was a very gangly, skinny kid. My nicknames were Muscles because I had none—I was just a skeleton with skin—and Ovaltine, which is a chocolate drink that kids were supposed to drink to make them gain weight.So you have always been a visual storyteller, even as a child. Drawing was the only thing I was really interested in. My father would bring paper home from the factory. They were order forms that were plain on the back. I would draw all kinds of characters and adventures. I wasn’t really good at anything else. My high school shop teacher took the tools away from me after about three weeks. He said, “You’re going to hurt yourself! Go get some paper and sit over there and draw.” I did, and I was very grateful for the chance to do that.

Did you go to art school in Indiana? Yes, I did. I went to art school for four years, but it didn’t prepare me for the real world of commercial art. I had to learn that when I got to New York.

Why did you move to New York CIty right after you graduated? I couldn’t find any work in Indiana, but I had friends who were going to Cooper Union. They said, “Better to be out of work in New York than out of work here. Come along.” So I went along and wrapped packages at Macy’s for a while. I worked for a lettering studio and then for a necktie fabric-designing firm. And then finally, I got work making cartoons for filmstrips and slides.

What kinds of cartoons were they? They were for sales meetings and promotions. A writer would write a script and the cartoonists would try to add humorous situations. We did work for Arrow Shirts, American Standard Plumbing, and Maxwell House Coffee—all sorts of products. The hardest part was convincing the salesmen that what we were drawing was going to be funny. They usually didn’t get the jokes.

Working on those cartoons must have been good training for a future picture book author and illustrator. I had a lot of fun trying to inject humor into a very dry script. It was good practice.

Nobody ever said, “Hey, that’s good,” or “Thank you.” You just did it. It went out the door. You never heard anything about it. But when I did the books, children began writing to me. I thought, “This is great. Somebody noticed.” Kids let you know if they like something. The Clifford books have humor young children can enjoy and can understand. It’s very hard to write humor for that age group. What’s the secret of your success? I read one time about a silent film comedian whose name I can’t recall now, but he was very popular. He was a very funny guy, and then somebody told him how good he was, and he got to thinking about it. And when he started thinking about what he was doing, he ruined it. Instead of acting upon his natural instincts, he began planning, and things fell apart.

The Clifford books have humor young children can enjoy and can understand. It’s very hard to write humor for that age group. What’s the secret of your success? I read one time about a silent film comedian whose name I can’t recall now, but he was very popular. He was a very funny guy, and then somebody told him how good he was, and he got to thinking about it. And when he started thinking about what he was doing, he ruined it. Instead of acting upon his natural instincts, he began planning, and things fell apart.

Do you have a favorite Clifford book? I always liked Clifford and the Grouchy Neighbors. A lot of children have neighbors who complain, “Don’t come into on my yard! Don’t step on my lawn!”

I thought that could happen to Clifford. The characters look like my mother’s neighbors back in Indiana, but the fact is, they were very nice, considerate neighbors. I hope they never noticed that the grouchy neighbors look like them. Grace Maccarone is Holiday House’s executive editor.

Grace Maccarone is Holiday House’s executive editor.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Clifford the Big Red Dog 500 Festival Parade Float «

[...] SLJ’s Interview with Norman Bridwell [...]Posted : May 03, 2013 10:19