The Fine Art of Working with Parent Volunteers

School librarians must navigate a host of issues when considering when, and if, to use volunteers: how to train them, avoid leaning too heavily on volunteers, and entrust them with complex tasks.

|

Student grandmother Harriet Camp volunteers as a “shelving angel” at Bradford K-8 School in Littleton, CO.Photo courtesy of Bradford K-8 School (CO) |

Volunteers in your school library should lessen your daily workload. While they’re making sure your space stays organized and useful—with the added bonus of parent participation—a team of volunteers reshelving books, helping create displays, and assisting with inventory frees you to address bigger issues, including reestablishing connections with students post-pandemic and brainstorming ways to support classroom teachers.

In practice, though, school librarians have to navigate a host of issues when considering when, and if, to use parent volunteers. These concerns include how to train them, how to avoid leaning too heavily on them so as not to harm chances of retaining a full-time aide, and how to entrust complex tasks to willing volunteers.

"I’ve been a lone person who relied heavily on volunteers, and I’ve had a part-time aide," says Denise Cushing, digital teacher librarian at Bradford K-8 School in Littleton, CO. While an aide requires some oversight, corralling a squad of volunteers—training them, scheduling hours, and deciding what they should do—calls for superb management skills, Cushing says.

|

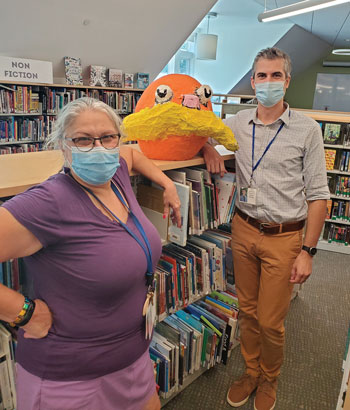

Camp with digital teacher librarian Denise Cushing.Photo courtesy of Bradford K-8 School (CO) |

Coping during COVID-19

Bridget Crossman, librarian at Lake George (NY) Elementary School, has a full-time aide in her small school of 280 students, but she relies on volunteers during the school’s semiannual book fair. The three-day event is often paired with a student-created activity, and it has become a big event in town. Parents help children select books, answer questions, and ring up purchases.

When COVID-19 rules kept parents out of schools, Crossman adapted by running her fair outside, even though it was winter. She used teacher volunteers and had parents sign up for time slots and then drive through the fair in the school’s small bus loop.

In terms of raising money, "it was probably the most successful book fair we had," she says. The school repeated the outdoor idea last spring, but by then parents and students were able to walk among the book carts to pick their purchases.

Ryan Tahmaseb relies on volunteers for many tasks in his library at the Meadowbrook School of Weston, a private K–8 school in Weston, MA. He already has a staff assistant, but he fully realized the worth of parent helpers when he was required to do without them during COVID-19 restrictions last school year.

The director of library services, Tahmaseb took on the extra responsibility of teaching a section of English last year, closed half his library to students, pivoted to an online order form for checkouts, and created a "surprise me" online book forum where students could share their favorite books. He managed to keep his circulation about the same as in a typical year. But with no volunteers and new quarantine requirements, it wasn’t long before piles of books began to overwhelm his space.

Once the school started employing substitute teachers, Tahmaseb asked some of them to help with shelving during their downtime. "It went a long way to help with overflowing," he says. With vaccinated parents allowed back on campus, Tahmaseb expects to train small groups of parents so they can catalog, prep books for circulation, or audit. The audits help Tahmaseb discover which books listed in the catalog aren’t on the shelves, so he can reorder titles if needed.

Student privacy concerns

Kelsey E. Bogan, the library media specialist at Great Valley High School in Malvern, PA, avoids volunteers altogether in order to safeguard her students’ privacy, she says.

"I want [my teenage students] to feel absolutely certain the library belongs to them; that it’s a place they can exist without judgment from adults," she explains. Bogan and her assistant work hard to build relationships with students and teach them that their choices—from any questions they might have to what books they read—are private.

"I have the incredible privilege and honor to be one of the very few adults in a teenager’s life who isn’t responsible for any of the pressures they feel," Bogan says.

She includes parents in library happenings through active social media accounts, and gives frequent tours of the library and speaks to parent groups regularly.

Tahmaseb doesn’t have the same privacy concerns with younger students. But his volunteers don’t manage book checkout or do tasks that would bring them into contact with students’ personal information.

"For me, the physical labor and relationship-building that comes with [parents’] help far outweighs any privacy concerns," he says.

|

Director of library services Ryan Tahmaseb (right) with his assistant, Liz Canella, at the Meadowbrook School of Weston (MA) library.Photo courtesy of the Meadowbrook School

|

Handling an army of volunteers

Carolyn Foote, who recently retired from her job as a librarian at Westlake (TX) High School, inherited several volunteers when she started her job. She also reached out to a new parent organization at her school to find more, and she did. "They were trying to meet people and get comfortable with the school," she says.

Foote took the time to get to know volunteers, having them fill out a survey asking what tasks they wanted to try and what they absolutely wanted to avoid. "Over the years, I found some love to shelve, and some are crafty and want to slice up bookmarks at the paper cutter."

She had her volunteers do everything from processing new books to preparing displays, scanning items during inventory, and hunting for missing items. Volunteers helped with book fairs, prepared materials for makerspace activities, and shifted books when shelves became too full.

Foote created a schedule for her army of volunteers, setting up time slots from thirty minutes to two hours. Remaining flexible was important, she says. She kept a running list of tasks that needed to be done, so if a volunteer came in when the staff was busy, they would be able to pick a job and get started.

Diane Mokuau, the librarian at Molokai (HI) High School, deploys volunteers in a variety of projects inside and outside the high school. But Mokuau, one of SLJ’s 2021 School Librarians of the Year, calls on students or college students to help in her library.

Mokuau’s own volunteer work in her community played a role in drawing library volunteers. Because the island of Molokai is so close-knit, it was natural for Mokuau to help others, she says. When she began a high school club to send island students to the mainland for college visits, people she had assisted in the community willingly pitched in to help out with fundraising and use their contacts to set up meetings for the students when they visited campuses.

Although Tahmaseb was already using volunteers, he took to Twitter this summer to ask peers if he was missing any tasks they could take on outside of reshelving, book covering, and helping to staff the school’s book fair. Enthusiastic replies mentioned that he might use parents to help with displays, cataloging, and inventory.

Tahmaseb’s volunteers also help secure visits from authors and illustrators by taking on the work of contacting publicists. He doesn’t schedule volunteers to come in while the library is holding classes to avoid too much noise and distraction. Tahmaseb also creates a volunteer schedule and leans on parent preferences when handing out jobs such as reshelving or cataloging books.

Foote says her best volunteer wasn’t a parent at her school, but a grandparent. "She loved to repair books, and we relied on her," Foote recalls. During COVID, the grandparent even took books home to work on them when volunteers weren’t allowed in schools.

The best volunteer is often either a former librarian or a long-term volunteer who is familiar with how the media center is run and can handle more intricate tasks.

"I had a volunteer who worked with us for years," Foote says. The volunteer would stay all day to work with an aide on inventory: "She loved to find lost books."

One of Mokuau’s more dedicated volunteers regularly takes books home to cover and catalog them. But sometimes, volunteers can be more work than help, Mokuau says. One person offered to help, but ended up asking so many questions and veering off task so often that she stopped using him. "He was not what I needed," she remembers.

Cushing doesn’t offer volunteers too many creative jobs and has parents mostly reshelve books. She will have them do shelf reads, make sure books are filed correctly, and pull books to be evaluated for weeding.

Staffing questions

With media center staffing constantly under pressure, many librarians try not to use parent volunteers in place of needed professional aides. "I wish we didn’t have to wrestle with this," says Tahmaseb.

"There are always concerns about staffing," Foote says. "People don’t always understand what librarians do." While people suggest volunteers for vital tasks in the library, no one ever recommends using volunteers instead of teachers, she adds.

Tahmaseb expressed similar concerns: "I wish the value of the library was more obvious and didn’t need to be evangelized."

Mokuau has intermittently had staff aides during her 19 years at the high school. Volunteers who are consistent, show up regularly, and stay for more than one year if possible, offer her the most extra help, she adds.

The number of volunteers Tahmaseb has varies from year to year, making them harder to count on, he says.

Beyond assisting with tasks, Foote noticed another benefit of having parents volunteer. Some volunteers’ children become more involved with library programs at her school of 3,000 students. They suddenly started hanging around the library, talking with staff, and bringing friends. "We develop a relationship and get to know their friends," Foote says.

Foote also created a library advisory committee that examined libraries throughout the school system and asked members for advice about how to make sure libraries stayed current. That allowed her to attract community members outside the parent pool, such as business owners, city librarians, and a museum director. The group became invested in making each school’s space valuable for students.

During a budget meeting, discussion turned to whether the district could cut library staff. An audience member interrupted and told the board that she volunteered in the library and she could vouch for the staffing needs.

"They really listened to her," Foote says.

Wayne D’Orio writes frequently for SLJ.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!