2018 School Spending Survey Report

Teaching “Black Lives Matter” | SLJ Talks to Educator, Author Renée Watson

In the wake of a grand jury decision not to indict a New York police officer in the chokehold death of Eric Garner, an unarmed black man, educator Renée Watson offers advice on how teachers and students can broach recent events.

Renée Watson

“How should we talk about Ferguson with our students?” was the scheduled topic for the “Teachers Teaching Teachers” (TTT) discussion on Wednesday, December 3. By the time of the Google hangout at 9 pm ET, the event’s panel of educators was still processing what had happened earlier that day, when a grand jury declined to indict a New York police officer in the chokehold death of Eric Garner, an unarmed black man. SLJ spoke with Renée Watson, a member of the TTT panel, who offers a unique perspective as both an educator at DreamYard, an arts education organization in the Bronx, NY, and author. Her books include Harlem’s Little Blackbird: The Story of Florence Mills (Random House, 2012) and the upcoming YA novel This Side of Home (Bloomsbury), due out in February 2015. Watson has also worked as a writer-in-residence, teaching creative writing and theater in public schools and community centers nationwide. The TTT conversation was very powerful. Particularly given the Garner decision, emotions were very raw among your fellow educators. And I bet the same thing is happening in schools across the country. How can teachers help kids in dealing with their emotions? Yes, emotions are still raw for many of us. It’s been a heavy week. Here are a few ideas for helping young people process their feelings:- Give students time to express how they feel in silent journal writing. You might want to share prompts that can be optional for students to respond to.

- Make art. Collage is a great activity; making something whole out of broken/torn pieces can be therapeutic. In their work, students can ask a question, honor the life of one of the slain, or make a powerful statement. Besides images, I often provide quotes, lines from poems, and famous speeches for students to use if they want.

- Listen to a freedom or protest song and discuss it. Ask students to think about why musicians make these types of songs. What lyrics would they write if they created a song about what’s happening now?

- Refer students to get more support, if needed. For teachers who might feel uncomfortable talking in depth about the recent events in our nation or feel like students need more support than they can give, refer students to the school counselor or arrange for a guest to come in.

- Share picture books. There are great titles to introduce younger grades to social justice. Visit www.usingtheirwords.org for a list of books recommended for grades K-5 by pre-service teachers.

For detailed lesson plans, activities, and discussion questions, I’d recommend “Teaching About the Jordan Davis Murder Trial.” (Edutopia). “If we’re doing our jobs as educators, I don’t understand how you’re not having this conversation,” you said Wednesday. For those who haven’t already, how would you recommend launching such a conversation in class? I believe classrooms should be spaces where young people learn history, discuss and understand current events, and learn skills to apply in their future to create a better world. I try to set the expectation from day one with my students that we discuss what is happening in our world, which means, they are expected to watch the news, read the newspaper, pay attention. For educators who do not normally talk about current events and/or have not talked about race, power, injustice in their classrooms, I think starting with an honest acknowledgment of what’s happening can be a place to start. I think letting students know that we are human, that we care about what is going on in the world, and that we are thinking about what’s happening is important. A teacher I know told her students, “I don’t know if you all have been paying attention to what’s been happening, but I have. And I have a lot of questions and I’m not sure how to talk about it but I just wanted to acknowledge that there’s a lot going on. If anyone wants to talk, I can find support for you.” She went on to teach her lesson, but taking this first step to bring it up let students know that it’s okay to have feelings about what’s happening. She referred the two students who came to her after class to the school counselor. Other teachers asked students to write their questions about Ferguson on an index card. The teachers reviewed the questions and held a joint class discussion, where they shared the facilitation of responding to the questions. I also know of schools that held assemblies and forums after school for students who signed up. Also, I wonder how these discussions are playing out in predominantly white classrooms and communities? I believe we should provide opportunities in our classrooms where students see themselves in the curriculum and where they have to empathize and step out of their own experiences. We cannot reserve conversations about race, racism, privilege, power, and injustice to schools that educate children of color. We need young people—from all backgrounds—to take ownership of this democracy and see themselves as active citizens, change makers, and allies.

For detailed lesson plans, activities, and discussion questions, I’d recommend “Teaching About the Jordan Davis Murder Trial.” (Edutopia). “If we’re doing our jobs as educators, I don’t understand how you’re not having this conversation,” you said Wednesday. For those who haven’t already, how would you recommend launching such a conversation in class? I believe classrooms should be spaces where young people learn history, discuss and understand current events, and learn skills to apply in their future to create a better world. I try to set the expectation from day one with my students that we discuss what is happening in our world, which means, they are expected to watch the news, read the newspaper, pay attention. For educators who do not normally talk about current events and/or have not talked about race, power, injustice in their classrooms, I think starting with an honest acknowledgment of what’s happening can be a place to start. I think letting students know that we are human, that we care about what is going on in the world, and that we are thinking about what’s happening is important. A teacher I know told her students, “I don’t know if you all have been paying attention to what’s been happening, but I have. And I have a lot of questions and I’m not sure how to talk about it but I just wanted to acknowledge that there’s a lot going on. If anyone wants to talk, I can find support for you.” She went on to teach her lesson, but taking this first step to bring it up let students know that it’s okay to have feelings about what’s happening. She referred the two students who came to her after class to the school counselor. Other teachers asked students to write their questions about Ferguson on an index card. The teachers reviewed the questions and held a joint class discussion, where they shared the facilitation of responding to the questions. I also know of schools that held assemblies and forums after school for students who signed up. Also, I wonder how these discussions are playing out in predominantly white classrooms and communities? I believe we should provide opportunities in our classrooms where students see themselves in the curriculum and where they have to empathize and step out of their own experiences. We cannot reserve conversations about race, racism, privilege, power, and injustice to schools that educate children of color. We need young people—from all backgrounds—to take ownership of this democracy and see themselves as active citizens, change makers, and allies.

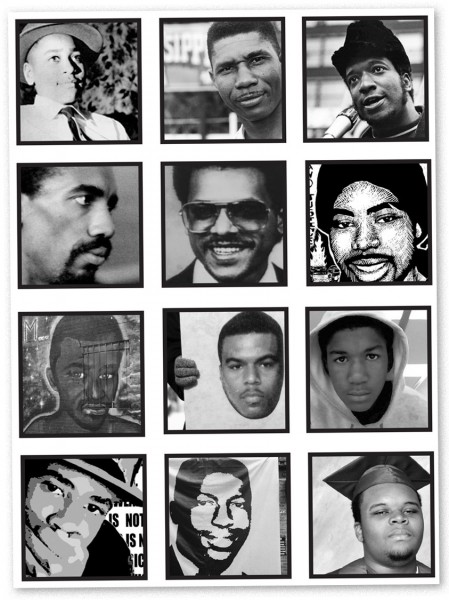

Courtesy of Rethinking Schools.

What about students who don’t want to talk about how they’re feeling? It’s not uncommon for students to not want to talk about how they’re feeling. Some students aren’t even aware of what’s going on, and there are others who know, but may not have strong feelings about it. In some cases, students may be desensitized to violence and injustice. I am constantly checking myself to remain open and not have any preconceived notions about what my students are thinking and feeling. My goal is not to make them feel or think any one particular way, but rather to get them to think and feel. I never want to force a child to speak. I want them to know that if they need or want to talk about it, they can. Sometimes, for difficult topics I facilitate one of the following activities.- “Stand Up If” or “Cross the Line.” These provide opportunities for students to express their feelings, share their experiences in a silent way. (For example, I might say, “Stand up if you have ever seen news reports about police brutality,” or “Stand up if you’ve ever felt angry).

- Image gallery. Create an image gallery of political cartoons, photos from newspapers, stats, etc. Give students post-it notes and have them write a one-word response or phrase in response to the image. Give clear instructions that this activity is silent and that students are not to respond to anyone else’s note. Play music in the background (freedom songs or something instrumental) to help set the tone.

Poetry is a big part of your teaching, as documented in your upcoming article for Rethinking Schools, "Happening Yesterday, Happening Tomorrow: teaching the ongoing murders of black men.” Willie Perdomo’s “Forty One Bullets Off Broadway,” about the killing of Amadou Diallo, has been a central work. But you also mention using Langston Hughes and Maya Angelou in the same lessons. Poetry has appeared to be really effective with your students. Why?

Art can provide a structured outlet for students to express how they feel. I think poetry works with young people because there is so much freedom. They can speak from their own perspective or someone else’s, , dream up a new outcome. I also make it a practice to share a photo of the poet, whose work we’re studying. I think when students understand artists as people who overcame adversity, who used art to take a stand, who were both flawed and brilliant, they find hope that they, too, can be creators and makers and continue the legacy. This same week marked the 59th anniversary of Rosa Parks’s refusal to move from her seat on a bus. That, as a lesson, is “civil rights with a bow tied around it,” said teacher Chris Rogers on TTT. How can we reconcile the historical struggle for democracy with what’s happening today, right now? I think it’s important to commemorate the Montgomery boycott. It’s a good way for young people to have context for the ongoing struggle for freedom and equality in our nation. When teaching about the civil rights movement—especially about Rosa Parks—it’s important to also teach about Claudette Colvin, to really help young people understand the planning, discipline, collaborating, and perseverance it took for the boycotters to organize. The problem is that educators often stop when the boycott ends and “they all lived happily ever after.” What’s more realistic, more inspiring maybe, is to say, “They won that battle and there many more to fight.” This way, young people see themselves on the continuum of change. If we can recognize and celebrate how far we’ve come while acknowledging how much work there is left to do, we can help students understand—and remind ourselves—that this is a marathon not a sprint. You’ve inspired students to express themselves in creative work. Is there anything of their's that you can share? Sure, here are a few poems by students. Never Written by A.M., high school student for Henry Dumas 1968, underground, day or night, coming or going, under the eternal florescent flicker of subway lights the clamor of wheels, crackle of electric current maybe muffled the shooting sound that silenced. One cop’s “mistake” two boys now to forever wait for their father’s face. A mind full of memory and make believe, stretched from sacred desert sands to sci-fi space and mythic lands, spilled out, running thick on worn concrete spans as subway doors open and close empty cars rattle ahead blank pages blown behind nothing but another man’s black body laid down in haste and waste. One Winter Day: a poem for Sean Bell by N.J., middle school student Blinded in the haze of 50 bullets. Shot by the same amount of candles on my mother’s birthday cake. I fell to the floor. Snowflakes fall slower than they appear to. I disappeared. Spirit gone before flesh could bleed. Glad we partied like we did in that Queens nightclub, toasting our futures. Didn’t know I wouldn’t see them again. Didn’t know life was going to end. Snowflakes melt faster than we want them to. For All of Them by L.V., middle school student Who scrubs the blood-stained train track, tile, lobby, car, sidewalk? Who tears down the yellow tape? Who sends the flowers and cards? Who sings at the funeral? Who watches the casket sink into the ground? Who can get back to their normal life? Who is holding their breath waiting for the next time? Who takes a stand? Who demands justice? Who knows justice may never come? Who keeps fighting anyway? Who fights by protest? Who fights by teaching? Who fights by writing a poem? Who fights by keeping their names alive?

Poetry is a big part of your teaching, as documented in your upcoming article for Rethinking Schools, "Happening Yesterday, Happening Tomorrow: teaching the ongoing murders of black men.” Willie Perdomo’s “Forty One Bullets Off Broadway,” about the killing of Amadou Diallo, has been a central work. But you also mention using Langston Hughes and Maya Angelou in the same lessons. Poetry has appeared to be really effective with your students. Why?

Art can provide a structured outlet for students to express how they feel. I think poetry works with young people because there is so much freedom. They can speak from their own perspective or someone else’s, , dream up a new outcome. I also make it a practice to share a photo of the poet, whose work we’re studying. I think when students understand artists as people who overcame adversity, who used art to take a stand, who were both flawed and brilliant, they find hope that they, too, can be creators and makers and continue the legacy. This same week marked the 59th anniversary of Rosa Parks’s refusal to move from her seat on a bus. That, as a lesson, is “civil rights with a bow tied around it,” said teacher Chris Rogers on TTT. How can we reconcile the historical struggle for democracy with what’s happening today, right now? I think it’s important to commemorate the Montgomery boycott. It’s a good way for young people to have context for the ongoing struggle for freedom and equality in our nation. When teaching about the civil rights movement—especially about Rosa Parks—it’s important to also teach about Claudette Colvin, to really help young people understand the planning, discipline, collaborating, and perseverance it took for the boycotters to organize. The problem is that educators often stop when the boycott ends and “they all lived happily ever after.” What’s more realistic, more inspiring maybe, is to say, “They won that battle and there many more to fight.” This way, young people see themselves on the continuum of change. If we can recognize and celebrate how far we’ve come while acknowledging how much work there is left to do, we can help students understand—and remind ourselves—that this is a marathon not a sprint. You’ve inspired students to express themselves in creative work. Is there anything of their's that you can share? Sure, here are a few poems by students. Never Written by A.M., high school student for Henry Dumas 1968, underground, day or night, coming or going, under the eternal florescent flicker of subway lights the clamor of wheels, crackle of electric current maybe muffled the shooting sound that silenced. One cop’s “mistake” two boys now to forever wait for their father’s face. A mind full of memory and make believe, stretched from sacred desert sands to sci-fi space and mythic lands, spilled out, running thick on worn concrete spans as subway doors open and close empty cars rattle ahead blank pages blown behind nothing but another man’s black body laid down in haste and waste. One Winter Day: a poem for Sean Bell by N.J., middle school student Blinded in the haze of 50 bullets. Shot by the same amount of candles on my mother’s birthday cake. I fell to the floor. Snowflakes fall slower than they appear to. I disappeared. Spirit gone before flesh could bleed. Glad we partied like we did in that Queens nightclub, toasting our futures. Didn’t know I wouldn’t see them again. Didn’t know life was going to end. Snowflakes melt faster than we want them to. For All of Them by L.V., middle school student Who scrubs the blood-stained train track, tile, lobby, car, sidewalk? Who tears down the yellow tape? Who sends the flowers and cards? Who sings at the funeral? Who watches the casket sink into the ground? Who can get back to their normal life? Who is holding their breath waiting for the next time? Who takes a stand? Who demands justice? Who knows justice may never come? Who keeps fighting anyway? Who fights by protest? Who fights by teaching? Who fights by writing a poem? Who fights by keeping their names alive? RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Robyn Estela

Hi Renee, I grew up in the Bx and am very much a social justice educator. I was recently employed in a predominately white intermediate school and am saddened by the ignorance most of my students hold in regards to the #BlackLivesMatter movement. I struggle with trying to incorporate its significance, in addition to notions of white privilege and social-cultural empathy--- without being too HEAVY for my young students. I want to say that one is never too young to understand and advocate for social justice...but I just don't know HOW. Do you believe this conversation belongs in elementary school? If so, how? And what considerations need be had? Thanks!!Posted : Jul 22, 2015 04:00

Orlando Villeda

Hello, I love this lesson. I am planning on wrapping up my semester using the structure you outlined in http://rethinkingschools.org/static/archive/29_02/RS29_02_watson.pdf . I am curious to the articles you had your students read in conjucntion to the poems. Cheers, OrlandoPosted : Dec 15, 2014 02:50