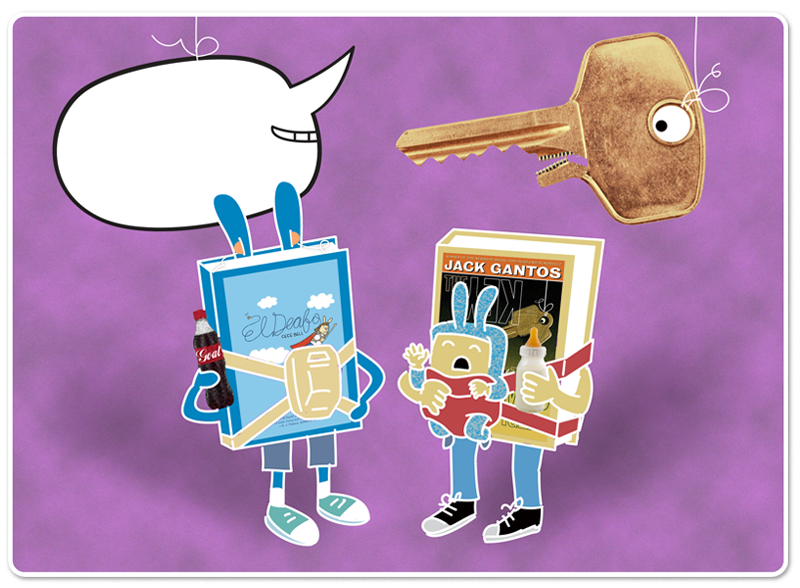

Round 2, Match 2: El Deafo vs The Key That Swallowed Joey Pigza

JUDGE – CAT WINTERS

El Deafoby Cece Bell

Abrams The Key That Swallowed Joey Pigza

by Jack Gantos

FSG/Macmillan

On the surface, there are two notable differences between the books in my assigned bracket: Cece Bell’s El Deafo is a graphic novel featuring people who look like rabbits, whereas Jack Gantos’s The Key That Swallowed Joey Pigza contains no illustrations, and instead of writing in speech balloons, he composes paragraphs that sometimes stretch well past an entire page.

At their cores, however, these are two middle-grade novels about kids who are struggling with all of their might to fit into their schools, their families, and their own bodies—bodies that have presented them with challenges that keep them from feeling normal and accepted.

Cece Bell’s autobiographical El Deafo opens with the words “I was a regular kid.” Cece was born with her hearing intact, but at the age of four she was stricken with meningitis, a health scare that left her “severely to profoundly” deaf. After a year of kindergarten spent in a school for the deaf, Cece finds herself in a new city with her family and in a new school filled with kids who can hear.

To help her adjust to her public school life, her doctor fits her with a Phonic Ear, an enormous box she must wear strapped to her chest, with little cords running up the sides of her head to two earpieces. Her teacher then uses a microphone that works with the box to allow Cece to hear all of her school instructions with clarity. An entertaining illustration shows everything that’s entailed with wearing a Phonic Ear on one’s little body, from the thick and sticky straps to the necessity of wearing an undershirt with a “cute rosette” to avoid sweating from the box. Yet even if Bell didn’t include a single graphic in the book, her discomfort and pluck would still come through the pages loud and clear. Her knack for storytelling, combined with a talent for conveying emotions through deceptively simple illustrations, makes for a riveting reading experience.

Throughout the book, Cece imagines herself transforming into “El Deafo,” her confident, cape-wearing alter ego who can tackle every obstacle thrown her way: her struggles to fit in at a birthday party, her mother’s push for her to learn sign language, her crippling lack of confidence when speaking to the boy she likes. More than anything, both Cece the girl and Cece the superhero desire a sidekick—a friend who will understand the challenges of her hearing disability without seeing her as simply a girl who can’t hear. My heart broke to pieces when one of her potential best friends turns off the lights at a slumber party specifically so Cece can’t read lips. Every time a new friend came along, I held my breath and hoped that Cece would indeed, at long last, find her sidekick.

Even though the characters in El Deafo look like rabbits (a fitting choice, considering the predominance of the ears), the book is extraordinarily human, insightful, inspirational, hilarious, honest, and moving. Cece’s experiences made me teary-eyed at least twice, and I lost track of how many times I laughed out loud. Truthfully, I forgot all about the fact that I was looking at cartoon characters with bunny ears, and I desperately hope readers don’t overlook this gripping story of perseverance simply because it’s a graphic novel with animals.

Like Cece, Jack Gantos’s titular Joey Pigza is at odds with his own body, but in his case it’s what’s happening inside his head that’s causing his problems and concerns. Joey has ADHD, to the point where he frequently plucks hairs out of his scalp and wears a yarmulke to hide the damage. His mother is suffering from a severe case of postpartum depression and has hidden Joey’s much-needed medicine, yet she sends him off to his first day back at his old school after a disastrous year of homeschooling.

With details both amusing and poignant, Joey describes the sensation of heading off to school without his meds, saying he feels “a little jangly inside like old Mr. Trouble was spying on me through a telescope and snickering while I marched directly toward an invisible trip-wire.” Joey’s new teacher proves to be helpful, however, and a class project in which Joey plays the Greek Oracle at Delphi allows him to practice his new goal of finding the “pawz-i-tive” in life. Things seem to be taking a turn for the better . . . until Joey’s desperate mother calls him back home to save her from hurting his baby brother.

The plot turns decidedly darker back at home and went down paths I wasn’t quite expecting after an opening that focused primarily on Joey’s goal of handling school life. Joey’s mother is so terrified of causing harm to her baby that she abandons her two boys and runs off to a hospital for help. She makes Joey swear that he won’t tell the authorities she’s left them alone, and he must promise that he won’t let their estranged father anywhere near the baby. Joey’s only companion during the whole ordeal, aside from baby Carter, is his friend Olivia, who hitchhiked to see him after being suspended from her school for her blind.

Some humorous scenes are peppered throughout Gantos’s novel, most notably Joey’s attempts to run out to a store to buy Olivia new underwear. For the most part, though, I found the book to be an emotionally difficult read. Gantos doesn’t shy away from showing the darkness of mental disorders and family dysfunction. He delves deep into the minds of all of his characters, and those minds are often struggling with self-doubt and depression. A meat cleaver hidden in the house comes up repeatedly, and it’s an ever-present symbol of the dangers of living in an unstable home.

The Key That Swallowed Joey Pigza serves as an eye-opening window into the struggles that so many families unfortunately face, and Gantos is to be commended for his unflinching and lyrically written portrayal of lives that mirror those of countless modern children. Throughout the book, Joey learns to shed his fears about his own state of mind in order to save the rest of the family and his friend. His mother has asked him to be the man of the house, and he takes the task seriously, summoning the strength to become the best version of himself that he can be.

The Key That Swallowed Joey Pigza is Gantos’s fifth and final novel in the Joey Pigza series, but I hadn’t read the previous four books before sitting down with this one. I believe that my lack of previous Pigza knowledge makes this battle a fairer fight: El Deafo is truly up against The Key That Swallowed Joey Pigza and not the entire Joey Pigza series.

So . . . who won this particular bracket?

Both books skillfully demonstrate the ways children are able to find the power within themselves to overcome personal struggles, but in my opinion, El Deafo is the stronger and more plausible of the two books. Granted, El Deafo is an autobiographical novel, and Joey Pigza is, as far as I understand, a complete work of fiction, so the plausibility factor would naturally seem to tip in El Deafo’s favor. But Gantos’s novel had me questioning its believability as soon as Joey’s elementary school allowed him to leave on his own to stop his emotionally distraught mother from harming the baby. If the book wasn’t otherwise so steeped in reality, I’d be more willing to go along with the idea that no one at either the school or the hospital questioned the safety of the children and stepped in to help.

Bell’s El Deafo, on the other hand, portrays the challenges of Cece’s life in ways both believable and evocative. I felt every moment of the character’s pain and triumphs, and nothing—not even those bunny ears—pulled me out of the story. I devoured the book in one satisfying sitting.

I’m not normally one to seek out graphic novels, but El Deafo proved to me that powerful literature can indeed be created with the use of speech balloons, thought bubbles, and rabbits.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!