Black Nonfiction: Truth, Testament, and Good Trouble

Black nonfiction offers age-appropriate narratives to educate children and presents the truth needed for “recovery, reconciliation, and repair.”

The most frequent question I am asked about Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre is, “Why did you tackle that topic for children?”

In response, I ask, “Did you learn about the massacre as a child?”

If not, don’t blame your upbringing. Your parents and teachers probably weren’t taught about the massacre either, because the scant Black history in curricula was—and still is—apt to be whitewashed.

Unspeakable commemorates what is believed to be the nation’s worst incident of racial violence. From May 31 to June 1, 1921, a white mob waged a campaign of terror in the predominantly Black Greenwood community, leaving at least 300 dead and 8,000 homeless. Because Tulsa’s white leaders declared it a “riot,” Black residents could not file insurance claims to recoup losses, which totalled $200 million in today’s dollars.

By 1921, Greenwood’s Black Wall Street was the wealthiest African American district in the country. The one-mile stretch along Greenwood Avenue symbolized Black prosperity, fueling envy among white supremacists. The plot by white leaders and the police to destroy Greenwood erased Black Wall Street from the map and from memory. Seventy-five years later, an official investigation occurred. In 1996, the Tulsa Race Massacre Commission’s report exposed the conspiracy. But the massacre was not taught in Oklahoma schools until the 21st century.

|

The oldest Tulsa Race Massacre survivor, 107-year-old Viola Fletcher (shown here at a Tulsa rally marking the centennial commemorations) testified before Congress.Sue Ogrocki/Associated Press |

This past May, 107-year-old Viola Fletcher, the oldest living Tulsa Race Massacre survivor, testified at a congressional hearing on reparations.

“I still see Black men being shot, Black bodies lying in the street. I still smell smoke and see fire. I still see Black businesses being burned. I still hear airplanes flying overhead. I hear the screams,” Fletcher bore witness. “I have lived through the massacre every day. Our country may forget this history, but I cannot.”

Mother Fletcher’s testimony begs the question: Why weren’t we taught that history in school?

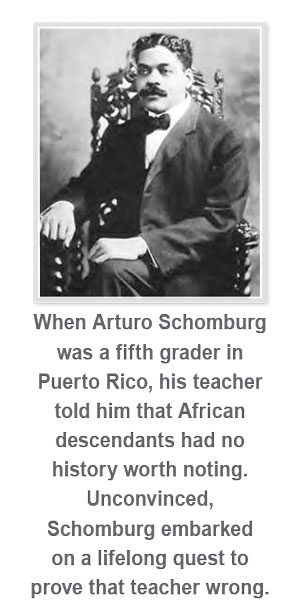

When bibliophile Arturo Schomburg (1874–1938) was a fifth grader in Puerto Rico, his teacher told him that African descendants had no history worth noting. Unconvinced, Schomburg embarked on a lifelong quest to prove that educator wrong.

After immigrating to the United States, he collected books, art, and artifacts about the African diaspora and became a leading light of the Harlem Renaissance. Donated to the New York Public Library in 1926, his collection formed the basis of the present-day Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. The Harlem repository holds more than 11 million items, including author Langston Hughes’s cremated remains, which lie beneath the lobby.

When I was growing up in the 1960s, few children’s books centered Black histories. But teachers at my all-Black elementary school in Baltimore infused our lessons with Black pride. My fourth grade teacher made us memorize Hughes’s poem, “I, Too,” which filled me with a sense of liberation.

Decades later, at a literary event in the Harlem brownstone that Hughes once called home, I admired his typewriter on the mantle and wondered aloud: “Is this place haunted?” Within minutes, a full water bottle—undisturbed by any visible motion—toppled from the stool beside me, as if I had summoned his ghost.

Just as my preacher grandfather saw ghosts, I am haunted by the ancestors’ untold stories of resistance, resilience, and remarkability. For me, Black history is a balm akin to church. I carry both sorrow and celebration to the altar of remembrance.

Just as my preacher grandfather saw ghosts, I am haunted by the ancestors’ untold stories of resistance, resilience, and remarkability. For me, Black history is a balm akin to church. I carry both sorrow and celebration to the altar of remembrance.

First and foremost, African American nonfiction is testament. By definition, Black testament encompasses tradition, tributes, trials/trauma, triumphs/transformation, and, to borrow from the biblical Proverbs, “training up a child.”

[Read: More than 50 Works of Black Nonfiction]

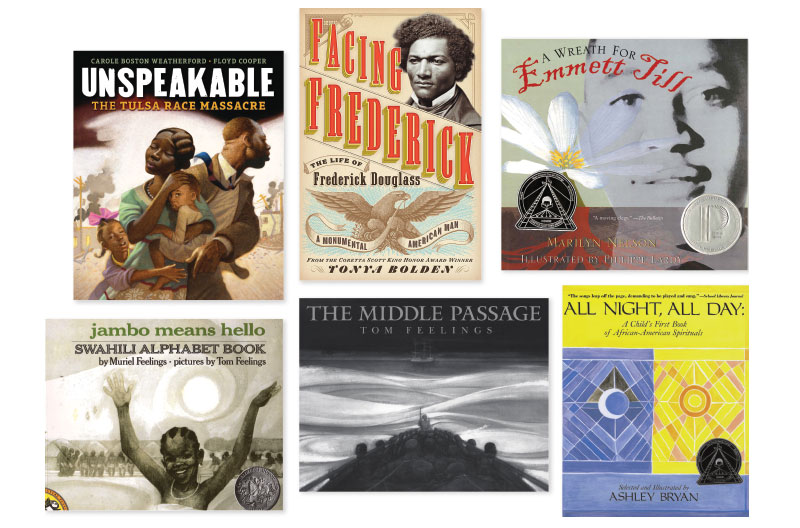

Testaments to tradition focus on family, arts, culture, cuisine, and community. My book, The Roots of Rap: 16 Bars on the 4 Pillars of Hip-Hop, illustrated by Frank Morrison, fits in this category. So do Ashley Bryan’s All Night, All Day: A Child’s First Book of African American Spirituals, and Ashanti to Zulu: African Traditions by Margaret Musgrove, for which illustrators Leo and Diane Dillon won the Caldecott Medal—a first for a Black artist.

Testaments in tribute include partial or full biographies, like my book R-E-S-P-E-C-T: Aretha Franklin, the Queen of Soul, illustrated by Frank Morrison; Before She Was Harriet by Lesa Cline-Ransome, illustrated by James Ransome; Jump at the Sun: The True Life Tale of Unstoppable Storycatcher Zora Neale Hurston by Alicia D. Williams, illustrated by Jacqueline Alcántara; and Facing Frederick: The Life of Frederick Douglass, a Monumental American Man by Tonya Bolden. Another recent exemplar is The Oldest Student by Rita Lorraine Hubbard, illustrated by Oge Mora.

Of the categories that I have delineated, tributes predominate, perhaps because there are so many African American luminaries who were for too long overlooked, making for a wealth of biographical subjects.

Testaments of trials and trauma include histories of oppression as well as memoirs, like Ordinary Hazards by Nikki Grimes andBrown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson. Of course, Unspeakable belongs here. A Wreath for Emmett Till by Marilyn Nelson and The Middle Passage: White Ships/Black Cargo by Tom Feelings, which document other atrocities, go under this heading—along with adaptations of Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped by Jason Reynolds and Sonja Cherry Paul.

Testaments of triumph and transformation commemorate historic events and collective action, as well as unsung heroes who overcame adversity and defied odds. I place my verse novel You Can Fly: The Tuskegee Airmen, illustrated by Jeffery Weatherford, in this category. Other examples are We Are the Ship: The Story of Negro League Baseball by Kadir Nelson and The Undefeated by Kwame Alexander, illustrated by Kadir Nelson.

Testaments to train up a child explore concepts, dispense wisdom, and sometimes take the form of odes, affirmations, and quotations. My most maternal and prayerful works, In Your Hands and Dreams for a Daughter—both illustrated by Brian Pinkney—fall in this category. Moja Means One: A Swahili Counting Book and Jambo Means Hello: A Swahili Alphabet Book, both by Muriel and Tom Feelings, are classic examples. More recent titles are This Book Is Anti-Racist by Tiffany Jewell, illustrated by Aurelia Durand, and We Rise, We Resist, We Raise Our Voices, an anthology edited by Cheryl and Wade Hudson.

Of course, some books overlap categories.

Children deserve and will demand the truth. Granted, teachers can’t teach what they don’t know. Often, Black nonfiction does double duty, simultaneously educating children and adults.

Black testament opens eyes, hearts, and dialogue. I write to fill in knowledge gaps, to honor the ancestors, to foster hope and healing among young readers, and to spark much-needed conversations among children and adults. Black nonfiction offers age-appropriate narratives to enlighten children early, before lies harden into denial and inherited prejudices into hatred. Truth is a prerequisite to recovery, reconciliation, and repair.

|

Langston Hughes’s poem “I, Too” filled Weatherford with a “sense of liberation.”Fred Stein/picture-alliance/dpa/AP Images

|

Black testament is crucial given the vector of white supremacy throughout American history. The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, the 1963 Birmingham church bombing, the 2015 Charleston church massacre, and the January 6 insurrection are all cut from the same white sheets. I wrote about the massacre for young readers because children—like the sisters depicted by the late Floyd Cooper on Unspeakable’s cover—witnessed, or perished in, the mob violence. I wrote about the massacre because Black youth are still victimized—by adultification, racial profiling, police brutality, and the school-to-prison pipeline. If Black children can bear the burden of systemic racism, then their peers can read about it.

As Fletcher attests, childhood trauma sears itself into the memory. Yet, even in Oklahoma, debates rage about teaching unbiased history in school. The reckoning after the police murder of George Floyd brought calls for authentic voices and antiracist pedagogy. White backlash has been swift and sweeping. In state after Republican-controlled state, legislatures have barred teaching about systemic racism on grounds that the truth might make some children uncomfortable. Where was this sensitivity when textbooks stereotyped Black, Indigenous, and people of color?

During the Harlem Renaissance, Hughes wrote, “An artist must be free to choose what he does, certainly, but he must also never be afraid to do what he might choose.”

My subjects often choose me. Long before the terms “diverse books” or “antiracism” entered the lexicon, cultural curiosity compelled me to rescue obscure Black figures and events. I channel muted, marginalized, and once-muzzled ancestral voices to break the chains of ignorance that shackle us to America’s original sin. Black testament has the power not only to set the record straight, but also to cultivate empathy, embolden young people to raise their voices against injustice, and make what the late civil rights leader John Lewis called “good trouble.”

I never shy away from painful truths, because children merit a more complete history. And I trust when they hear it, they will ask the right questions. After reading my books about systemic racism, children respond as if I had scripted them. “Who made those stupid rules? Why were white people so unfair?”

Adults must not avoid the truth because they fear children’s questions. Can I get a witness?

Carole Boston Weatherford’s 60 books include a Newbery Honor, three Caldecott Honors, and 2021 release Unspeakable.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!