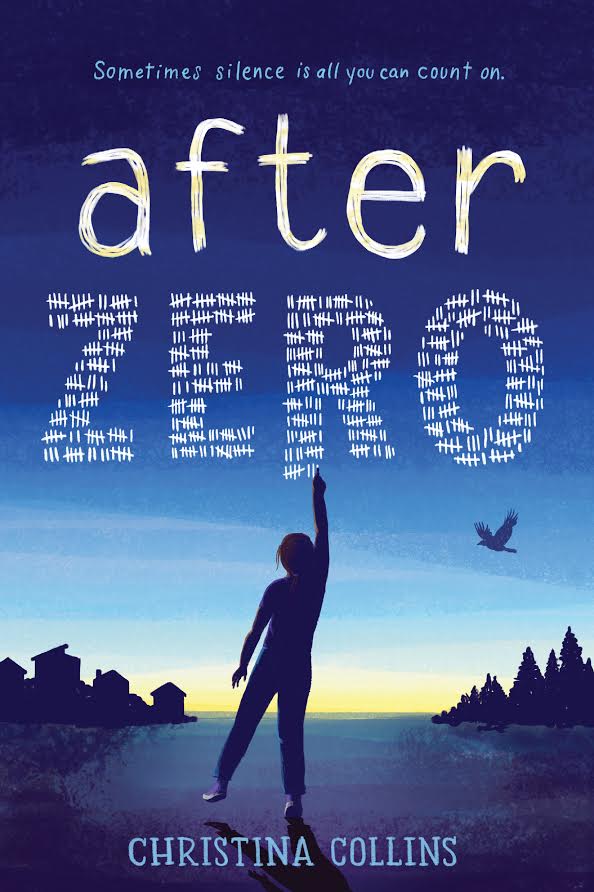

Q&A and Cover Reveal: After Zero by Christina Collins

A lot of librarians are familiar with books in which a character, maybe the main character or a sibling or a friend, does not speak. The term I always thought applied to this situation was “selective mutism”. It’s so common in books that when I keep track of the books I read on Goodreads I’ve actually made it its own category. Turns out, I may have had my terminology wrong all along. Today we sit down and talk with Christina Collins. Christina suffered from low-profile selective mutism as a child and has written the book After Zero, informed by her knowledge of what that entails. I was able to ask Christina some questions that cleared up a lot of my confusion and assumptions:

Betsy Bird: Selective mutism is so common in children’s novels that it is sometimes considered a subject heading in libraries. But while a lot of books contain characters that exhibit signs of selective mutism, not a lot is known about it above and beyond the fiction. From your own experience, what do you feel are some of the common misunderstandings connected to children that go through this?

Christina Collins: Great question! I’m glad you brought up the subject heading, because there is still confusion around that classification. Selective mutism actually isn’t common in children’s novels. Traumatic mutism is common, and it is often confused with selective mutism, though the two are crucially distinct. Indeed, many novels featuring traumatic mutism have been mis-assigned the subject heading “selective mutism” in library catalogues. In these novels, a character suddenly stops speaking in all situations as a post-traumatic response to a shocking incident, such as witnessing a loved one’s death. Sounds familiar, right? Selective mutism (sometimes called situational mutism), on the other hand, is an anxiety condition referring to someone who chronically doesn’t speak in certain situations where speech is expected, such as school, despite speaking freely in at least one other situation, such as home. There’s no causal link between selective mutism and trauma, and this condition can affect anyone, including kids with a loving family like I had.

So, to answer your question about common misunderstandings, the confusion between traumatic and selective mutism is definitely a big one. Another is the assumption that kids with selective mutism are choosing not to speak. In truth, their silence serves as an involuntary defense against extreme anxiety, which may cause them to physically tense up or freeze. A third misunderstanding is that kids with selective mutism are just very “shy”; shyness is not paralyzing in the way that selective mutism is. Mistaking selectively mute behavior for shyness, defiance, or a post-traumatic response can mean that children won’t get appropriate help and thus their condition may grow worse, even to the rare point where all situations eventually trigger silence (known as progressive mutism).

BB: How common is selective mutism? And do you feel that children’s books reflect the reality of the situation accurately, or are there misconceptions they inadvertently reinforce?

CC: Selective mutism primarily affects young people—reportedly about 1 in 150 children and 1 in 1,000 adolescents.[1] However, I wouldn’t be surprised if this is an underestimate because many cases go unrecognized. As for children’s novels that portray selective mutism, I’ve found only a dozen or so middle grade and young adult novels in the English language featuring a character identified as having selective mutism; just over half of those characters are protagonists. Most of the books help to correct the misconceptions I mentioned above, which is wonderful.

However, they overwhelmingly reflect a specific kind of experience—diagnosed, high-profile selective mutism—thereby overlooking undiagnosed and low-profile experiences. More specifically, the characters in these books are usually already aware at the start of the novel that they have selective mutism, and they’ve been receiving professional treatment for some time. While this experience is absolutely worth telling, so is that of undiagnosed kids who are struggling alone in confusion, unaware that what they’re going through has a name and convinced that they’re just “weird.” Furthermore, the books generally focus on high-profile selective mutism, but low-profile patterns exist and are just as important to represent. What’s the difference? Well, each person’s experience is nuanced and unique, but generally, individuals with selective mutism speak freely in at least one situation; however, in certain other situations, those with a high-profile pattern don’t speak at all, and those with a low-profile pattern may manage to speak minimally when absolutely necessary but don’t initiate contact or make requests. Both experience high anxiety levels in these situations, but low-profile selective mutism is more likely to be overlooked or dismissed as shyness because it’s less obvious.

BB: Let’s talk a little bit about your own book AFTER ZERO. You yourself suffered from low-profile selective mutism as a child. How did your experiences influence the creation of the book?

CC: Yes, while After Zero is a work of fiction loosely inspired by the Grimm tale “The Twelve Brothers,” the moments in which my protagonist Elise experiences anxiety about speaking are inspired by my past adolescent experience with low-profile selective mutism. As with many other kids and teens around the world, my struggle went unrecognized and undiagnosed, and understandably so, considering the lack of public awareness and knowledge of not only selective mutism in general, but also the differences between low-profile and high-profile selective mutism. I didn’t even encounter the term “selective mutism” until I was in college and had thankfully already overcome the worst of the condition on my own. Though my selective mutism fortunately never got as bad as Elise’s gets in the second half of the book, writing After Zero was a cathartic way for me to work through what I had experienced, drawing on memories from late middle school and early high school. I was later surprised to discover that none of the authors of novels I found featuring selectively mute characters seem to have had selective mutism themselves.

BB: What readership would you particularly like to reach with this book?

CC: I would love to reach kids who, like Elise, are struggling with anxiety and speaking, so they can know that they’re not alone, that help is available, and that their silence does not define them—that they are so much more than a textbook term like “selective mutism” or a label like “quiet.” I hope, too, that the book reaches readers of all ages who might know someone who has or had selective mutism, to hopefully foster empathy and raise awareness.

BB: Is there a reason you chose to write a work of fiction rather than a work of nonfiction?

CC: As a writer I’ve always gravitated toward fiction, but I also knew from the start that this book would be fiction because the idea for it came to me in the form of a retelling of a Grimm fairy tale, “The Twelve Brothers.” It did not end up as a retelling per se, but if you’ve read the tale, you’ll find most of its basic plot points in the novel. I’ve loved fairy tales since before I could read, but I discovered this one as a college student, shortly before I came across the term “selective mutism,” and the tale resonated with me for obvious reasons—it has a mute heroine. The tale seemed like a fitting pre-text for a modern story about a girl with selective mutism, so I derived the plot of After Zero from this tale while channeling some of my own experiences into the novel. Plus, I couldn’t resist a touch of raven-themed magic, which might broaden the book’s appeal to readers who normally stick to fantasy.

BB: Finally, the big question, what are you working on next?

CC: I can’t say too much yet, but I’m working on my second novel for Sourcebooks Jabberwocky, and I’m really excited about this one. It will be another middle grade, contemporary, standalone novel that tackles anxiety, this time concerning body image, a topic that’s just as important to me as selective mutism. Stay tuned!

[1] Source: Selective Mutism in Our Own Words: Experiences in Childhood and Adulthood by Carl Sutton and Cheryl Forrester

Many thanks to Christina for answering my questions. And now (drumroll please) . . . .

The Cover!

Many thanks to Stefani Sloma and the folks at Sourcebooks Jabberwocky for putting me in touch with Christina and giving me this reveal.

RELATED

Tide’s Journey

The Smushkins: ABC Zoinks

Whose Footprint Is That?

Our World: Vietnam

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!