Young Readers Editions: What Makes for a Great Adaptation of an Adult Book?

Whether readers are looking for an inspirational story about a chef, to get to know Megan Rapinoe, or to nerd out on grammar, the options are there. Plus: six stellar adaptations.

|

Illustration by Jacqueline Alcántara |

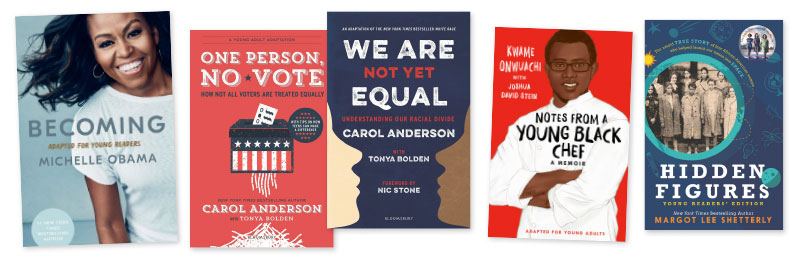

While young readers editions of adult books have been around for a long time, this year’s release of Michelle Obama’s Becoming: Adapted for Young Readers shines a spotlight on this ever-evolving catalog of titles. Young readers

editions (YREs) span mega-best-selling titles like Obama’s to riveting but lesser-known reads for tweens and teens.

We’re in a moment of tremendous growth in YREs, evidenced by the number of available options over the last five years in WorldCat. Whether readers are looking for an inspirational story about a chef (see Notes from a Young Black Chef by Kwame Onwuachi with Joshua David Stein), or to get to know Megan Rapinoe (see Rapinoe’s One Life: Young Readers Edition), or to nerd out on grammar (see Dreyer’s English: Adapted for Young Readers by Benjamin Dreyer), the options are there. These books are outstanding tools for classroom incorporation, reader’s advisory, and helping young readers dream big, all with inspiration from their favorite leaders.

But what are YREs, and what makes them different from their original publications? Where and how can they be used in schools and classrooms? And what elements make an adaptation irresistible to kids?

An introduction to the genre

For the most part, YREs straddle the line between middle grade and YA collections. They are often but not always designated for ages 10–14.

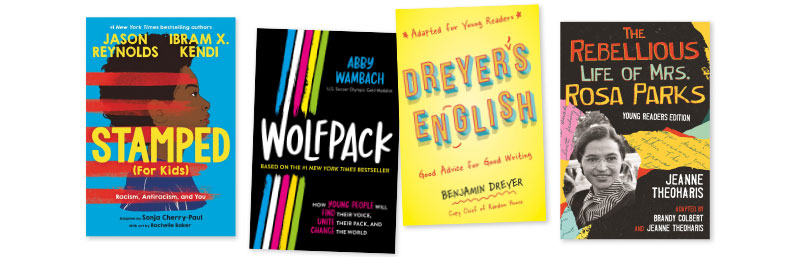

Buzzy, best-selling adult titles often see adaptations—alongside Becoming, other recent titles include Stamped by Ibram X. Kendi (adapted with Jason Reynolds), Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson, Hidden Figures by Margot Lee Shetterly, and Abby Wambach’s Wolfpack, adapted by Ruby Shamir.

Other adaptations have themes that readers in the target age group may be interested in and/or are about high-profile celebrities, politicians, and change-makers focusing on the person’s younger years. Among recent YREs, Jeff Chang and Dave “Davey D” Cook’s Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop dives into the history of hip-hop; Dear America: The Story of an Undocumented Citizen by Jose Antonio Vargas brings the story of being undocumented in America to tweens and teens; while The Beautiful Struggle by Ta-Nehisi Coates explores the challenges of coming of age in West Baltimore and the power of father-son relationships.

What’s most important is a story that can inspire and educate, while also offering young readers a window into the lives of powerful figures or movements.

“When adapting adult books by elected officials, civic leaders, and inspirational thinkers, one key imperative is to bolster stories about their childhoods,” says Shamir. “Many of them are role models. If kids can see what these leaders did as young people, and how far they rose, it could inspire them to imagine their own potential.”

|

From Left: Tonya Bolden strives to present new information and not oversimplify material for younger readers; Anton Treuer expanded on social activism and race relations in the young readers edition of his book; Author Brandy Colbert (at left) with ballet dancer Misty Copeland.From Left: Courtesy of Tonya Bolden;courtesy of Anton Treuer; Courtesy of Brandy Colbert |

Tonya Bolden, who has adapted Carol Anderson’s White Rage (the YRE is titled We Are Not Yet Equal) as well as Anderson’s One Person, No Vote, says that her goal—to find the space between presenting new information and not oversimplifying for a younger audience—is key to a strong adaptation. Tweens and teens can, in fact, understand weighty topics, she adds.

“The challenge is striking the right balance: making the book accessible but not watering it down,” she says. “There’s also the challenge of keeping the book engaging, the same challenge I face when writing my own books.”

Additionally, those who adapt books for young readers think broadly about what differentiates those from adult titles.

Brandy Colbert, who worked on the adaptation of Misty Copeland’s Life in Motion and The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks by Jeanne Theoharis, sees big differences in how much information is presented.

“In adult literary, which I adore, the writer is often given the time and space to linger in scenes just for the beauty of the prose—and I love that! Give me three pages about cooking a meal, all the way from bringing the vegetables home from the farmers market to how they got on the table, and I’m hooked,” she says. “But in YA, we’re encouraged even in quiet books to really hook the reader from the beginning and start with the action and maintain that pace throughout.”

Stories that resonate

Oftentimes, authors of adult books welcome the chance to write adaptations of their work. Reyna Grande, who wrote The Distance Between Us, was eager to adapt the book after hearing from educators who used the adult version in their teaching.

Her memoir is a coming-of-age story about life before and after coming to the United States as an undocumented immigrant. The title found its way into high school and college classrooms. Teachers and parents encouraged her to consider developing a similar story for younger readers. Grande proposed the idea to her agent, and it sold quickly.

“Adapting The Distance Between Us was very easy to do because the original book was already in a child’s perspective—[though] there was some adult introspection, reflection, backstory, but not much—and the voice was already there,” she says. “All I had to do was remove the parts where there was an adult point of view. I also removed scenes that were inappropriate for kids, [and] I had to comb through the chapters line by line and cut out as much as I could to reduce the word count.”

It was not all cutting, though. As a bonus, she was able to add more moments from her youth that would resonate with the tween and teen audience.

“I then set out to add things that aren’t in the original, such as my prom and the bus journey to Tijuana when the bus left my dad behind,” Grande says. “I also expanded a bit on my border crossing, because my editor felt kids that age would be engaged with that moment.”

When Grande does readings, no matter what age group the audience, she uses the YRE, as the chapters are shorter, tighter, and capture listeners’ attention more immediately.

Anton Treuer’s 2012 book Everything You Wanted to Know About Indians But Were Afraid to Ask gained traction among adults and high schoolers alike. The broad appeal of the book made it a solid candidate for adaptation; a YRE hit shelves in April.

“When we developed the young reader edition, we greatly expanded the content, especially around social activism, race relations, and contemporary topics,” says Treuer, a parent of nine children and an Ojibwe scholar. “We went deeper on culture. And every sentence was rewritten to create the greatest ease of access, rendering the entire book real, relevant, and relatable to young readers.”

“A lot happened since the adult version of the book was first published,” Treuer says, including the Dakota Access Pipeline Protest at Standing Rock, the confrontation at the Lincoln Memorial, the name change of Washington’s NFL team, the Cobell settlement, new successes and stresses around Indigenous language revitalization, and a new push for racial reconciliation. “The content is broad—history, politics, economics, culture, language revitalization, current events. People can read it all straight through or use sections and passages to spark discussion.”

A bridge in the nonfiction landscape

Educators can especially benefit from weaving YREs into their curricula, while librarians can offer YREs as companion reads based on student interest.

“Michelle Obama’s book would tie in nicely to a unit on recent presidents and first ladies, or the inner workings of the White House, or even Chicago,” says Colbert. “The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks would fit well into Black History Month lessons, of course, but also as additional reading during a unit about influential Americans, game-changing women, or civil rights.”

As for pleasure reading, “If [students] happen to love books about ballet and dance, why not show them [that] Misty Copeland, a real-life ballet dancer herself, has a memoir about her entrée into that world?” Colbert adds.

Hallmarks of YREs include tight pacing, compelling stories, and voices that resonate. Where an adult edition might assume readers bring their own knowledge and experiences to a book, YREs provide all the context. And some kids will pick up the adult version as their reading skills advance.

Shamir points out that nonfiction YREs bridge the gap between inspiring picture books and information often relegated to hefty tomes or encyclopedias.

“YREs have a way of speaking directly to kids, using kid-level perspectives, that respect, inspire, and ultimately empower young people to see and situate themselves in those subjects,” she says. “Topics like space exploration or civics get such vibrant and engaging treatment from picture books, and then the next foray into those areas typically had been through textbooks or biographies of great leaders in those fields. YREs offer a bridge in the nonfiction landscape.”

That bridge also enables communities developing One Book programs to engage readers of all ages: Adults and kids can enjoy the same book in whatever edition suits them. Bolden notes that one of the biggest joys in developing YREs is knowing that important works will be accessible to more readers.

Grande says her ideal reader is a young immigrant looking for stories of perseverance and seeking their dreams. “Because it is shorter and the reading level slightly lower than the original, [my book] gets used a lot in colleges in their ESL classes. So I have college students reading the adapted version and they like it,” she says. “This benefits many of our students who are struggling readers but who love books that elevate their understanding of the world.”

Treuer welcomes the opportunity for more cross-cultural connections. “Natives often get a sugarcoated version of Columbus and the first Thanksgiving, too. We all want and need the truth, genuine connection, and opportunities to engage,” he says. “The ideal reader is anyone open to that. I hope they will see that Native people are more than the sum of their tragedies. We are alive. We are here. We are ancient and modern—thousands of years of human history still in the making.” The power of adaptations for young readers means that more people may find these lessons and understand them.

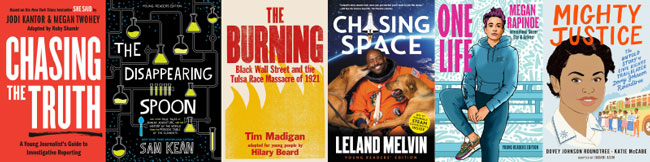

Six Stellar AdaptationsChasing the Truth: A Young Journalist’s Guide to Investigative Reporting: She Said Young Readers Edition by Jodi Kantor & Megan Twohey, adapted by Ruby Shamir. Philomel. Sept. 2021. This book explores the workings of investigative reporting and best practices in journalism while chronicling how the Harvey Weinstein story was researched and reported. The Disappearing Spoon: And Other True Tales of Rivalry, Adventure, and the History of the World from the Periodic Table of the Elements Young Readers Edition by Sam Kean. Little, Brown. 2018. The Burning (Young Readers Edition): Black Wall Street and the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 by Tim Madigan, adapted by Hilary Beard. Holt. May 2021.

One Life: Young Readers Edition by Megan Rapinoe. Razorbill. Sept. 2021. MIghty Justice: The Untold Story of Civil Rights Trailblazer Dovey Johnson Roundtree by Dovey Johnson Roundtree & Katie McCabe, adapted by Jabari Asim. Roaring Brook. 2020. |

Kelly Jensen is an editor at Book Riot and the editor of three YA anthologies, including Body Talk, (Don’t) Call Me Crazy, and Feminism for the Real World.

RELATED

Tide’s Journey

Whose Footprint Is That?

The Tiniest Giant

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!