Virtual YA Book Clubs and Other Reading Initiatives for Incarcerated Teens

Well-organized literacy programs help kids in detention access and talk about books.

|

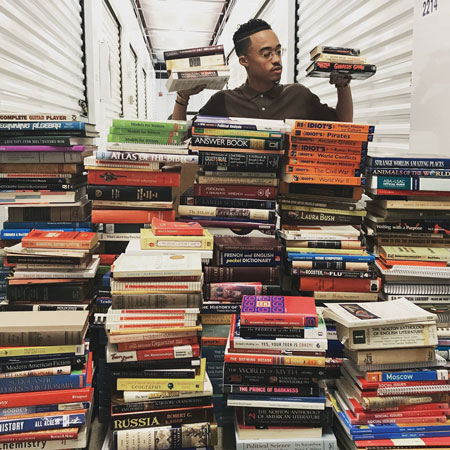

Dieter Cantu, founder, Cantu’s Books to Incarcerated Youth ProjectPhoto courtesy of Dieter Cantu |

Stephanie Mitchell is the rare librarian who hopes she doesn’t see her patrons again.

Like most librarians who work with adolescents, she delights in fulfilling requests, turning readers on to new books and authors, and connecting with teenagers. But because she works mostly at the Pima County Juvenile Court Center in Tucson, AZ, seeing a reader for a second or third time probably means the youth has landed back in trouble.

“I tell them, ‘I’m really not happy to see you again,’ ” she says.

On any given day, nearly 60,000 youths are incarcerated in juvenile jails and prisons, according to the ACLU. The vast majority of these children don’t have access to libraries or books they can read for pleasure.

Library programs in juvenile facilities across the country are sporadic. Some efforts are run by volunteers who try to supply books for youths, while others are a formal part of the public library in the area where the detention center is housed.

It was a lack of access to books that drove Dieter Cantu, a formerly incarcerated teen, to start Cantu’s Books to Incarcerated Youth Project, a nonprofit that creates libraries at Texas juvenile justice facilities, including the Ayres Halfway House in San Antonio, Giddings State School in Giddings, and Cottrell Halfway House outside of Dallas.

Cantu was detained at three different detention centers in Texas when he was younger. Two didn’t offer any books, and the third had only outdated ones.

Still, he says, “Reading always helped me stay out of trouble and keep my mind clear.”

Upon his release in 2009, Cantu launched a number of initiatives, one of which was to build mini-libraries in the state’s detention centers.

He says he tries to discern what career aspirations the teens have and then ensures that they have access to the appropriate materials so they can prepare to work when they are released. One detained child said he wanted to be a barber. “I said, ‘Let’s prepare you for that and read about it,’” he says.

“If there’s a school-to-prison pipeline, I want them to have an exit plan,” Cantu adds.

While his group started off cobbling together financial and book donations wherever he could find them, Cantu now has well over 5,000 books circulating. Books aren’t checked out, per se, but are given to, and sometimes returned by, interested students. His group has expanded its work to facilities in Illinois and Oakland, CA.

Though facilities are mandated to provide education to juveniles in their custody, that doesn’t have to include the use of a library, says Jeanie Austin, a jail and reentry services librarian at the San Francisco Public Library and author of Library Services and Incarceration: Recognizing Barriers, Strengthening Access (ALA Editions), released last month.

“There are few expectations that public libraries offer a collection or services at detention centers,” says Austin. And when programs do exist, “there’s no standard way of doing it.”

Despite the current lack of coordination nationally, Austin adds, “There’s an interest in doing this work that hasn’t existed for a long time. We need [new] models, we need to see what’s happening.”

In Pima County, Mitchell works about 14 hours a week serving the detention center that houses anywhere from 25 to 50 youths. Although book checkout is self-service, Mitchell says she tries to meet one-on-one with each admitted youth to introduce herself and describe what the on-site library can offer.

|

Dieter Cantu speaks at the Amador R. Rodriguez Juvenile Boot Camp in San Benito, TX.Photo courtesy of Dieter Cantu |

The average stay for a teenager in the Pima facility is about 20 days, Mitchell says, although some come and go within a day or two. Regardless of how long teens are there, Mitchell tries to make sure each leaves with a free book (currently, Jason Reynolds’s Long Way Down), a public library card, and an understanding that Pima’s network of libraries can offer more than just books: Internet access and snacks are also available at any of the county’s 27 library branches.

While incarcerated youth have always benefited from these programs, it’s difficult to create and sustain them. Though Pima’s program at the detention center has operated for at least 15 years, Mitchell and Beth Matthias-Loghry, the services manager for Pima County Public Library, hope to expand their services to the youths who are part of Pima’s adult detention center.

“For every kid in juvenile detention, there’s one in an adult center,” Mitchell says. “We don’t have a presence there. It’s our next focus.”

A lack of services is why a New York City teacher started Literacy for Incarcerated Teens (LIT) in 2002. The nonprofit supports the school library collections at New York City’s eight juvenile justice detention centers and works with a residential girls’ facility on Long Island.

Robert Galinsky has been with LIT for years. Since the pandemic started, Galinsky, a writer, performer, and media coach, has connected nationally known authors, musicians, and actors each week with the teenagers participating in book, music, and movie clubs. Galinsky runs the regular Zoom sessions at seven different New York facilities, including Rikers Island, one of the city’s prisons notorious for its harsh conditions.

The hour-long sessions devoted to books aim not only to connect the teens to various titles but also to peel back the curtain of creativity and encourage incarcerated children to create art.

“It can be difficult to crack the armor they put up to protect themselves,” Galinsky says. “They have faced so much trauma. But if we can open the possibility and show them a light, they follow it.”

Galinsky says that when an author commits to a session with the incarcerated youths, he acquires a batch of books and ships them to the detention center, giving teens a couple of weeks to read the material and find out about the author.

While some discussions can be difficult, others are fun, he adds. When Kaitlyn Greenidge came on to discuss her book Libertie, a historical novel based on Susan Smith McKinney Steward, the first Black woman doctor in New York State, the teens told Greenidge how much they loved her nails and eyelashes. It wasn’t the conversation Galinsky was expecting, but he let it go, and the group talked fashion for a good part of Greenidge’s session.

“Part of what we’re doing is letting the girls be human,” he says. “They’ve been told they are wrong so often. I like to tell them, ‘Nothing you are doing is wrong.’”

That message can go a long way. After being released from Brentwood, one formerly incarcerated student and workshop participant, Jennarai Earp, performed a poem, live, during a poetry night that Galinsky runs at a New York City bookstore.

The first, and most important, step toward creating library services for incarcerated youths is to partner with the groups running the facilities, experts agree.

“We’re successful primarily because we have the support of the detention agency,” says Mitchell. “We’re guests in their facility.”

Matthias-Loghry says when she started the library at the Pima County Juvenile Court Center, the relationship with detention administrators wasn’t great. The facility library was stretched for staffing, so Matthias-Loghry scaled down the program so she could better support it. Books are kept at the facility and don’t go between the regular library and the facility.

The books that Pima County offers detained teens aren’t part of the library’s regular collection. They have to meet the detention center’s guidelines, which means no hardcover books, staple bindings, or depictions related to sex, drugs, or gangs.

Urban YA is a popular genre, and Mitchell says the library has learned not to try to bring in items officials will require them to censor, including magazines and some of the mainstream manga series. “We don’t want to spend hours with a marker when we could be interacting with youth,” she says.

The library has a system to remove hardcovers from books, she says, and because there is an understanding about what content material shouldn’t include, there is rarely an issue.

Holly Neill Whelan, manager at Arapahoe Libraries in Colorado, offers self-service checkouts at the county’s adult detention center. While some deputies resist her program, many see its benefits, she says. Whelan ran a “one book” event for both prisoners and detention guards, who read the YA novel Allegedly by Tiffany D. Jackson. Whelan says the story, about a teenage girl who’s been navigating the justice system since age nine and is trying to clear her name, was a page-turner that allowed rich opportunities for conversations between staff and prisoners.

Cantu’s good relationship with officials is one reason he was allowed to drop off books during the COVID ban on visitors to juvenile facilities, he says. He learned early on that if he didn’t follow the chain of command, the 10 boxes of books he dropped off could easily end up in a locked room and prisoners would not be able to access to them.

Mitchell says programming beyond getting books into kids’ hands often requires a presence and follow-up that she can’t offer during her limited hours. Some of her programming involves challenging teens to find great first lines in books or to write a book review of something they read to describe it for fellow detainees. The school in Pima County’s detention center is focused on self-reflection, and Mitchell hopes to launch a journaling project that will tie into students’ schoolwork.

When Mitchell was working at a branch near the facility, a teen approached her. “It’s me,” he said. At first Mitchell didn’t recognize him, because he had shaved his head. But after he introduced himself, she realized that she’d met him in the detention center. To know that connection was important enough for him to seek her out later was encouraging. “Just knowing that’s possible is heartening,” she says.

Strong Connections

“Galinsky has really created a community with these girls,” she says. “It’s cool to mention I had a lot of anger issues, got into a lot of trouble.” She told the teens about realizing something had to change in her life and talked about her problems, which helped the girls warm up to her.

Sarah Deming (left), the author of the YA novel Gravity, a book about a teenage girl boxer, said the discussion of boxing during her visit became so animated that one of the correctional officers jumped up from his seat to join in.

Deming is a Golden Gloves champion herself. During her session, students asked about the punching bag she had hanging in her office, and the author ended up showing the girls some combinations. Anici Mrose Rissi, who wrote the YA collection Hide and Don’t Seek: And Other Very Scary Stories, Zoom-visited with the girls around Halloween. She was surprised when the teens acted out one of her tales, which is told entirely through text messages. “It was so fun to hear how it sounds in their voices,” Rissi says. Bottom: LIT’s Robert Galinsky with former Brentwood Residential Center detainee Jennarai Earp at a Manhattan poetry reading where Earp performed in October. |

Wayne D’Orio is a frequent contributor to SLJ.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Poet Yelda Ali (right) first joined a LIT Zoom session at the Brentwood Residential Center for Girls in Dix Hills, NY, that centered on her poetry collection, Outlet. Ali, an artist and activist focused on women’s rights and mental health advocacy, found the time so moving that she asked to continue. Ali has cohosted 10 sessions with Robert Galinsky since then. She says her discussions with the teens have touched on a variety of topics, from literacy to suicidal thoughts to the trouble she got into as a child.

Poet Yelda Ali (right) first joined a LIT Zoom session at the Brentwood Residential Center for Girls in Dix Hills, NY, that centered on her poetry collection, Outlet. Ali, an artist and activist focused on women’s rights and mental health advocacy, found the time so moving that she asked to continue. Ali has cohosted 10 sessions with Robert Galinsky since then. She says her discussions with the teens have touched on a variety of topics, from literacy to suicidal thoughts to the trouble she got into as a child. “I- had girls who for two weeks didn’t look at me

“I- had girls who for two weeks didn’t look at me “It broke down that barrier” that exists between guards and the incarcerated teens, Deming says. “It was a nice moment that transcended the grim surroundings.”

“It broke down that barrier” that exists between guards and the incarcerated teens, Deming says. “It was a nice moment that transcended the grim surroundings.”

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!