Daniel Nayeri's Design-Centered, Studio Approach to Kid Lit | Up Close

Courtesy of Tae Won Yu

Daniel Nayeri came to the United States from Iran when he was eight years old. Finding comfort and confusion in classic works—he loved the clarity of Richard Scarry but found Dr. Seuss mind-boggling (“I couldn’t always tell the made-up words from the real ones”), he recalls how empowering it was when an elementary teacher allowed him to count his “Transformers” books toward his summer reading goal. Now the director of children’s publishing for Workman, the endlessly energetic Nayeri leads a unique team mandated to create not just books, but “great art objects for great and terrible children.”

Tell us about this mandate. “Art object” means that we care enough about our books to call them art. We’re not an in-house packager of commodities. But at the same time, we know that to a kid, a good fart joke is an art form. So we’re not too pretentious about it, either.

What was your guiding vision when you came to Workman? My model is extremely team-oriented, extremely people-oriented. [We function] like a little studio inside of a publishing company. First, I went talent shopping. I wanted to know who the best art designer in the industry is. And I found Colleen AF Venable. She had been at First Second at the time....So I called her up—I didn’t actually know her yet—and asked her for three hours of her time. Just three hours to pitch her on this idea. And then, [I asked her to] give me five years. I wanted to see if, in five years, we could make a division that does things people haven’t seen before. We did the same thing for pretty much everyone in the group. They were all chosen with great fear and trembling.

What’s a typical creative meeting look like? There’s a group of eight—the brain trust—and we meet on Tuesdays. I consider it my job to make that room the most productive, creative space it can possibly be. The team is made up of designers as well as an in-house inventor. We’ll come up with an idea and if it’s good enough, we’ll immediately start iterating a prototype. Often it involves 3-D modeling and 3-D printing. Sometimes it will involve physically cutting down other books and making them into the shape and size we want....This is all happening before any contracts are in place. [We rely on] that cliché from the tech industry: fail fast! Get to a place where you’re experiencing the book as soon as possible. It’s very design-first. When we prototype something, [we’re looking for] what’s magical, what’s amazing. If it doesn’t have [those qualities], it goes away. I have a shelf of dead prototypes. It’s like the island of misfit books. But when it does happen, we sometimes call it “unabashed whimsy.” You know it when you see it.

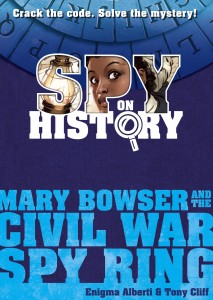

I’d love to sit in on one of these Tuesday meetings. It usually starts with an insane prompt. For example, I’ll say something like “I keep reading about how they can print the entire U.S. Constitution on a grain of rice. How do they do that? Is that lasers? Can we do that with lots of colors?” And our inventor will roll his eyes. “But what if you put layers and layers of paper down and you cut through the layers…?” And then later on our inventor will be like, “Huh. That could work.” So we begin with mechanics—what is a book doing? People often ask if we start with the format or the content first. Neither. We come up with the dynamic first. We ask ourselves, what does a kid want to do with this book? How are they actively learning, making, with this object?Tell us about a recent project you’re proud of. I’m so excited about our “Spy on History” books. What if, as you’re reading about someone who’s  excellent at something, you are also becoming better at that thing? So if you read a biography of Michael Jordan, you are not also, necessarily, becoming better at basketball. But, if you read our book on Mary Bowser, you actually are becoming better at spying. Mary Bowser is one of the most criminally ignored figures, who was instrumental in helping win the Civil War. She got memos from Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis, encrypted them, and smuggled them out in the linings of Mrs. Davis’s skirts. She has this action movie of a life. So our question was, while you’re learning about her, can you also be doing something? We had to study cryptology and layer in codes into the design and narrative.

excellent at something, you are also becoming better at that thing? So if you read a biography of Michael Jordan, you are not also, necessarily, becoming better at basketball. But, if you read our book on Mary Bowser, you actually are becoming better at spying. Mary Bowser is one of the most criminally ignored figures, who was instrumental in helping win the Civil War. She got memos from Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis, encrypted them, and smuggled them out in the linings of Mrs. Davis’s skirts. She has this action movie of a life. So our question was, while you’re learning about her, can you also be doing something? We had to study cryptology and layer in codes into the design and narrative.

You started out your career in adult books before moving to children's literature. There’s this belief that children’s publishing is a kinder and more welcoming culture than adult publishing. Has that been your experience? Sure, to some extent....But for someone like me, I don’t necessarily fit in a lot of ways. I hear things like “He’s a young man in a hurry!” And I hear [myself described] as “brash” quite a bit. But...there’s a good reason I tasted both [children’s publishing and adult publishing] and firmly grasped on to children’s literature. I believe whole hog in what we’re doing. We really are reaching an audience that is at its most limber, mentally, ethically, [and] morally. I mean, name a book that you read after the age of 19 that changed your life. When you’ve made books for adults and children, you see the difference. All those clichés are true.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Liza Peoples

Ms. Parrott is no longer to be trusted. Her reviews dissing well written and creative children's books in the name of political correctness is a throwback to censorship during the Spanish Inquisition, National Socialist Germany and the Soviet Union. Her attempt to control what writers create for our children has no place in a free society. Who elected you Queen Censor. How dare you!Posted : Jan 02, 2017 07:36