Nikole Hannah-Jones Talks to Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi About Their Book, “Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You”

Nikole Hannah-Jones, founder of the 1619 Project, spoke to Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi about their collaboration on Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You.

|

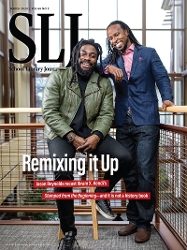

Jason Reynolds (left) with Ibram X. Kendi at the Antiracist Research and Policy Center at American University.Photography by John Boal |

Nikole Hannah-Jones, founder of the 1619 Project, spoke to Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi about their collaboration on Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You.

Nikole Hannah-Jones It’s been an amazing few years for both of you, racking up awards, best sellers. And Jason, you were recently named the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature. That’s fantastic. Congratulations.

Jason Reynolds Thank you very much.

Hannah-Jones What a time to be a Black creative. I feel like across literature, art, theater, music, film, we’re experiencing another renaissance. And I have to say, I’m really proud every day to be working in concert with you all and so many brilliant Black minds.

So, both of you, can you talk about how it feels to be a writer, particularly a Black writer, right now?

Reynolds For me, I’m always thinking about who I’m in conversation with, and am I working in tradition? That does matter to me, but only in the instance that I’m moving and pushing and evolving said tradition, creating new traditions within said tradition.

So I feel really humbled and held accountable for what I’m making, for who I am making it for, to make sure that I’m honoring the people who have come before me, and to make sure that I’m making space and seats at the table for the people coming after me. So, it’s special. And you’re right, it does feel like here we are in the midst of another renaissance.

Hannah-Jones So, who are you writing for?

Reynolds I write for Black children. It does not mean that Black children are the only people who read my books, obviously, but they are who I have in mind when I’m working.

I want to write something that is for them, and about them, that speaks the language that they know, that does not need to be explained, [sort of a code] that is woven into swathes of our culture, to make sure that they feel emboldened, that they feel seen, and visible, and big, and human. I think that is my primary goal.

Hannah-Jones Yeah, that’s beautiful. I’ve been asked that a lot pertaining to the 1619 Project. I say I expect different people to get different things from it, but that I was clearly writing this as a love song to Black folks specifically.

And you can definitely see that sentiment when reading any of your work.

So, Ibram, answer the same thing for me, if you would. How does it feel to be a Black writer in this moment?

Ibram X. Kendi I feel constructively challenged, because there are so many great and innovative writers who I admire, who I read across genre and across sector, who I feel are at the top of their games. I feel like, collectively, we’re adding to a longstanding tradition, a radical and creative tradition, but simultaneously, we’re creating our own tradition.

I feel like I do my best work [when I’m part] of a really good team. And there’s a really good team of young Black writers who, in many ways—we’re supporting one another. And we [recognize] our particular roles and strengths, and even weaknesses. So again, I just feel constructively challenged. And I think that’s a good thing.

Hannah-Jones I think so, too. Who are you writing for?

Kendi As an academic, we’re not supposed to have an audience. So with each of my books, I did not necessarily have a specific audience in mind while I was writing.

But then when I read back through them, it became clear who it was written for. So, my first book on Black student activism was for our current generation of student activists. And my last two books on racism, those were primarily meant for Black people who are just starting to understand how they can be a part of the struggle.

Hannah-Jones So, it seems to me that who you are writing for and the audience you are writing to are not necessarily the same thing.

The 1619 Project was not just to Black people. In much of my work, I know who the audience is going to be. And I’m writing for an audience, but to a people. Do you understand what I’m saying?

Kendi Yeah. I think it’s the same thing for me. I knew specifically with Stamped from the Beginning that the book would primarily be consumed by white Americans, by academics.

But at the same time, I knew how transformative it could be for Black people.

Hannah-Jones I was very excited when I saw that this book [ Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You] was happening. You guys collaborating on this is like uniting two superheroes who have varying powers. So, I wonder, how did this collaboration come about in the first place?

Read: SLJ's review of Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You

Reynolds Me saying no, over and over again. Like you say, we have varying powers. And I know exactly what my strengths and weaknesses are. So as somebody who is far from a scholar, this was really intimidating for me.

And I was very honest with Ibram. I didn’t pretend like I’m busy. It was like, “Bro, I don’t think I can do this.”

I’m used to invention, and this felt very different from that. It felt a little more structured, which is tough for me, in terms of having the information right there in front of you, and having to figure out how to synthesize and then disseminate that information in a different way.

All of it felt really difficult, borderline disrespectful. I felt like I was gonna not do it justice.

To his credit, he continued to ask. “You can do it. And I want you to do it.” I said no. And he continued to ask. Eventually, it was a yes.

Hannah-Jones So, as a writer, I’ve thought about how it would feel to be given a text and then asked to write it for a different audience. But it’s not your text. It’s not coming out of your mind. Although how you rewrite it is coming out of your mind. That seems like a very challenging thing.

Reynolds Yeah, it was the hardest thing I’ve ever had to wrap my mind around in my career, by far. This is all of his thinking, his work. How do I turn this into a different version of itself? And make it something fresh at the same time.

Hannah-Jones I can only imagine. In some ways, it felt disrespectful, even though I know you were trying very hard not to. So, on one hand, to be true to his material, but also to have the freedom to write it in a way that was true to you. That must have been really agonizing.

Reynolds Bummer.

Hannah-Jones So, Ibram, how did you decide on this collaboration, why Jason?

Kendi I think it originated when I was writingStamped from the Beginning. I was thinking about the term nonfiction novel. Because I wanted the book to have a very strong plotline, with character development. Everything that happens in a novel and attracts readers to a novel makes them accessible while allowing people to seamlessly consume the information.

So when we started talking about a YA version, I thought, you know what? A novelist would be best suited to do this.

But not any novelist, obviously. One who is deeply reflective and is a serious intellectual, so they could grasp the concepts. But also someone with their own flair, their own voice. Someone who is able to get into the head of a 12-year-old or a 16-year-old and tell a story that will inform and captivate them…

Someone with the ability to transform that into a Jason Reynolds book.

Hannah-Jones How did it work exactly? Because I have to say, I’m very possessive and jealous of my work and my words. The thought of turning something over to someone to rewrite is very hard for me to even fathom.

So did you just write the thing, Jason, and then send it to Ibram? Give me an idea how this worked.

Reynolds Ibram and I… the first thing that happened is we had breakfast. And he’s like, “Look, man. I want you to take the reins on this thing.” And the publisher said, “Look, Jason, you can do an edited version of Stamped from the Beginning,” which I thought was a terrible idea at the time.

I mean, I’m not an editor. I was like, I have to do this ground-up. And Ibram was cool with it.

Thankfully, he sent me the overarching theme of every chapter. It’s a cheat sheet, basically.

“Here are things that are nonnegotiable,” he would say. “These things have to be there in order to hold on to the [bones] of this narrative.” All of which I was really grateful for, because it served as a true north while I was trying to suss this thing out. But when I went to actually begin to make this thing happen, my confidence wasn’t where it needed to be.

So the first two drafts of this were, in fact, edited versions of his book. Poorly edited versions at that. And so we hit this wall—because I’m struggling. Remember, the pressure is on.

To be honest with you, I’d be lying if I said that it didn’t matter that I’m at a high point in my career. So, not only is the pressure on in terms of my respect for Dr. Kendi, I also don’t want to blow this. I don’t want them to be like, “Oh, we always knew. There it is. He blew it with the most important work that he may do in his career. He blew it.”

I had lunch with Lisa [Yoskowitz], our editor for this book. And she said, “Jason, the reason that he wanted you, the reason that we brought you on, is because we want you to do your thing. Do the thing that is you.”

“Well, I just want you to know that in order for me to really do that, I have to ruin his book.” And they said, “Well, give it a shot.” That’s why the first line is “This is not a history book.” It’s basically me figuring out that I had to be me, and who I am is irreverent. And what young people want is irreverence. They want someone to say, “This ain’t what you think it is. I know you’re used to a textbook. This ain’t that.”

The moment that I was able to start with that first sentence, “This is not a history book,” it’s like being reintroduced to myself. Then it was party time. At the end of the weekend, I have six chapters done. And then a month later, I turned it in. And that was that.

Hannah-Jones Wow. That made complete sense to me.

I love talking to other writers about process, because I know there are some who want constant feedback, like sending sections or chapters. I am not like that. I feel too exposed to send something before I’ve had a chance to complete it and revise some. It sounds like that’s kind of how you guys operate as well.

Reynolds Yeah. They’re not getting nothing from me until it’s done. Ain’t no writing groups, ain’t none of that.

Hannah-Jones So, why was it important to turn Stamped from the Beginning, a brilliant and game-changing book, into a book for young readers? And I would argue that Jason’s version makes this book accessible not only to a younger audience but also to adults who would struggle to read such a heavy text. Why was this important?

Kendi Well, when I went out and toured for the book, people would say every high school and middle school student needs to read this book, “but it’s just too sophisticated for them to grasp.”

I feel, without question, that young people can understand the history of racism in this country. As a college professor, I have had so many students tell me, “I’ve never learned this before, in high school, in middle school,” which means they wanted to know it earlier.

And I think that you have older people who are scared to or don’t know how to teach the history of racism to young people. This book can show how they can have these conversations and, simultaneously, help them to overcome their fears.

When they see the ways in which young people are responding to this text and applying it to their own lives… I’m hoping it completely throws open the door to more conversation and more literature on racism for young people. For me, that’s one of the grand plans for this book.

Read: A Remix for Right Now: A not-a-history history book begs the next chapter on racism | Editorial

Reynolds I’m on the ground, right? I’m with kids every day, in schools, I’m in prisons, and at rec centers. I’m in the projects, and the courtyard. And what I know, having toured for a gazillion years at this point, is they’ve been ready to have this conversation.

When I was on tour for All American Boys, and we were talking about police brutality, and privilege, and bias, I’m talking to sixth, seventh graders. And everybody’s ready to rock. I had 14-year-olds come up to me and say, “I’m white. I’m 14. But I want to figure out what my role is in this conversation. I want to know how to be less harmful.” Fourteen-year-olds.

I think it’s incredibly arrogant for adults to believe that young people aren’t ready or don’t want to have this discussion. It’s the insecurity of adults that continues to be a blockade for kids who are dying to stretch themselves emotionally and mentally.

And lastly, I think it’s important if language truly is the cornerstone of culture, then as language evolves, as we continue to explore the lexicon around race and racism in this country, the culture around race and racism may also evolve attached to that lexicon. So, imagine if a 12-year-old who is white—or Black, for that matter, or gay—grows up in this country, and by the time they’re 18 or 21, this no longer has to be an uncomfortable conversation because they have language to attach to it.

What an amazing thing to think about.

Kendi Teaching young people about racism and antiracism protects them. So, that’s the irony. People think they’re protecting these young people by not teaching them. Can you imagine, you’re a 15-year-old Black boy, and you’re constantly harassed by police. And you don’t understand the [nature of police] brutality and harassment and profiling. That then causes you to look in the mirror and think that they’re harassing you because there’s something wrong with you.

But if you understand the way racism operates, you’ll know there’s nothing wrong with you and everything wrong with police brutality.

Hannah-Jones So, you all literally just answered like five of my questions right there. I agree 100 percent. I first bought a book on slavery for my daughter when she was maybe three years old. There’s never been a point when we haven’t talked about race and racism. And people ask me all the time, “How do I talk about race in a way my kids can understand? And how do I make it easier for them?”

Hannah-Jones So, you all literally just answered like five of my questions right there. I agree 100 percent. I first bought a book on slavery for my daughter when she was maybe three years old. There’s never been a point when we haven’t talked about race and racism. And people ask me all the time, “How do I talk about race in a way my kids can understand? And how do I make it easier for them?”

I can only reflect on my own parenting philosophy, which is you teach it honestly and you don’t make it easier, because racism is not easy. And their experience of it won’t be easy. I think we have to try to protect our children as long as possible, but also give them the armor that they need to go out into the world and be as unscathed as possible.

And it does seem that’s the spirit of this book in that it arms Black children in particular with the knowledge and the language that explains the world that blames them for their conditions. And for white children and other children, it shows that racism is not this thing where you are either George Wallace or Martin Luther King, that you’re either a rabid racist who uses the N-word, or you’re Mother Teresa. As the book says, most people are in between, and they fluctuate.

So why is this, the particular language of this book around racism, antiracism, [assimilationists, segregationists], why is the language important in arming our youth at a time when their ideas about the world and their place in it are being formed.

Kendi I think that language helps us understand some of the built-in, inherent racism in the middle ground. As we form our opinions about the world, we tend to default to the middle ground because it feels the safest. And when I say the middle ground, I mean assimilationism, especially for Black folks.

I grew up in a household where we were taught to assimilate because my mother, who grew up in the ’50s, felt like this is how you survive in this country. If you want to live, then you’re going to have to bend a little bit. But at the core of that, the poison of racism is still there.

I wonder how my worldview would have changed and how I would have navigated my teenage years differently if I realized that antiracism is the antithesis to racism, and that assimilationism is not.

As I chronicled in How to Be an Antiracist, by the time I graduated from high school, I thought there were all these problems with Black people. Not biological problems, but behavioral problems that were holding us back. And I was constantly told that by not only white people, but even older Black people.

Hopefully, this book will start students out, much earlier than we did, understanding the intricacies of racism, as opposed to trying to understand the problems of Black people or people of color.

Reynolds I was in the youth department of a DC jail doing a talk, maybe a year and a half ago. One hundred percent Black. And I said, “Why don’t y’all think there are any white people in prison?”

One of the brothers said, “Because white people don’t make mistakes more than once. We keep messing up. We mess up and mess up again, and that’s why we’re here. They don’t do that. They mess up once, and they don’t never mess up again.”

A lot of them were there for stealing cars. Myself and a counselor told them that three miles across the bridge in Virginia, their crimes are joyriding misdemeanors. Joyriding. But in their neighborhoods, they serve hard time.

Those young men believed that they were there because something is inherently wrong with them. “White people don’t make mistakes more than one time.” This is what they literally said to me. The most heartbreaking thing I ever heard.

Hannah-Jones Man, the power in that and understanding that books can transform the way [you] think about yourself in the world.

So, in thinking about this interview for School Library Journal, I thought a lot about my school libraries when I was a kid. And I was a voracious reader. But I specifically remember the first time I saw a book with a Black girl on it, and it was Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. I snatched the book up because none of the books I saw in our library had Black girls.

It ended up, of course, being very typical that if there were Black children featured in stories, it was either a slavery story or a Jim Crow story. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it’s just kind of stark. Our children, it seems, are growing up in a very different literary world. The books on the shelves at my daughter’s school, the books that I bring home for her, look very, very different.

And she’s really into graphic novels. She recently brought home a graphic novel based on Little Women, except there’s a Black character, a white character, a Latinx character, and an Asian one. And I really loved Little Women as a child. And despite being in a different era, characters being a different race, I saw myself in Jo, which is the beauty of the universal story.

But we all know that the universal story, until very recently, never included us, and that sends a very distinct message. So my daughter is really conscious of representation and its power. She’s only nine years old, but she pointed out to me how she appreciated that every type of girl could see themselves in the book.

And that was meaningful to her. Not just that there were Black girls, but that her classmates who are Latinx could also see themselves. Why is it important that we shake up this canon, and that more voices and perspectives are included, and that other children besides white children get to see themselves as the universal story?

Reynolds Because other children besides white children exist. This is one of those conversations that I’m always having with people about “Oh, well, why is representation important?” Because there is more than one kind of person. White people aren’t the only people who exist in this country.

And so we need as much representation as possible, because young people, at the end of the day, need to know that somebody else outside of themselves knows that they exist. Bearing witness to young life is important. For young people to know that someone is bearing witness to their lives is incredibly important, incredibly valuable, incredibly empowering.

Books that show Latinx kids, and Black kids, and brown kids, and gay kids, and differently abled kids, and neuroatypical kids, and all the different sorts of young people, it validates their experiences and it validates their existence.

Read: An Educator's Guide to Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You

Kendi Yeah. And I think, in addition to representation, it’s important to give kids a critical racial lens when they’re reading literature.

And that’s what Stamped does. It’s going to give kids a critical analysis of racism and antiracism, which is going to further draw them to Jason’s other books, and others that are being written for them. But when they’re forced to read other books for school, they’ll be able to critique the hell out of that.

When their teachers give them a book that’s littered with racist ideas, they’ll be able to pick it apart. “How dare you assign us this book?” And here are all of the reasons why. I wish that I could be that fly on the wall when that kid, after reading this book, does that to a teacher.

Reynolds Oh, god. Can you imagine? I can hear all the critics about this generation being too sensitive. We could use a little more compassion, no?

Hannah-Jones We really could. It’s never a bad thing. And I don’t understand why so many people think it is. Particularly fostering that sense of compassion in our children. Compassion for other people does not diminish your own importance in the world.

This has been an amazing conversation, and I’m not even going to mention, Jason, that you got breakfast with Ibram. I’m still waiting on my breakfast.

Reynolds I knew that was coming.

Hannah-Jones Exactly. You know me, I don’t let anything go.

About the author: Nikole Hannah-Jones is an award-winning investigative reporter covering racial injustice for The New York Times Magazine and creator of the landmark 1619 Project. She co-founded the Ida B. Wells Society for Investigative Reporting, a training and mentorship organization geared towards increasing the numbers of investigative reporters of color.

About the author: Nikole Hannah-Jones is an award-winning investigative reporter covering racial injustice for The New York Times Magazine and creator of the landmark 1619 Project. She co-founded the Ida B. Wells Society for Investigative Reporting, a training and mentorship organization geared towards increasing the numbers of investigative reporters of color.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Mugabo Uwilingiyimana

So excited to read this work! Will come down for comments afterwards. I was just at Nikole's talk at Middleburry College this evening. Electric! Love that woman and the work she is doing.

Posted : Feb 26, 2020 06:23

sps S

What a treat to read about each author's writing process--and to see the dynamic between these three brilliant minds. More articles like this, please, SLJ!

Posted : Feb 25, 2020 04:41