Censors Bypass Reconsideration Policy

As attacks on library collections escalate, school boards and parents circumvent the established process.

|

|

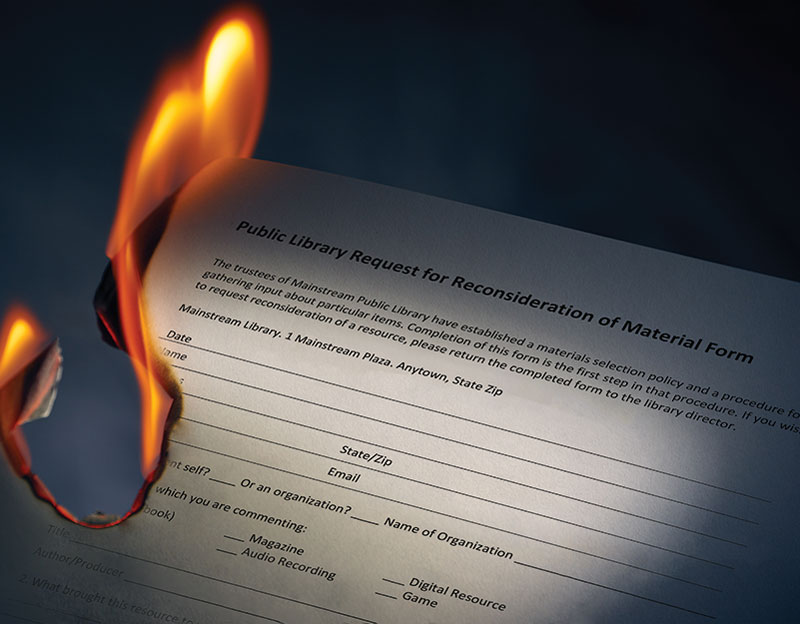

SLJ montage. Flame by wwing/Getty Images |

In the end, it was all blather and no blaze.

A Facebook event inviting community members to a book burning at the Dec. 13 Spotsylvania County (VA) Public Schools board of education meeting garnered national attention and condemnation (of Facebook, and the anonymous event organizer). The post and page disappeared within a few days. Still, the county sheriff warned publicly that such a bonfire would be

illegal. And when the time came, police officers watched over the parking lot, and the call to destroy titles checked out from the district’s school libraries went unheeded.

While the destruction was averted, the lasting message is dangerous and clear: Those seeking to remove books from school shelves are intensifying their efforts. It is not only the threat of book burnings. In some places, parents are attempting prosecution of library and other school staff. And throughout the country, the formal process outlined for book reconsideration is being ignored.

As complaints rise, formal challenges aren’t filed in many cases. Instead, there is outrage after selective read-alouds at public meetings—in some cases the books are not even in the district’s collection—and board members are taking unilateral action.

Librarians already juggling full schedules and, sometimes, multiple schools, must now respond to a flood of complaints, while also trying to find the best solution. In the past, the answer to challenged books has been to have a solid reconsideration policy and adhere to it. That remains the first and best line of defense. But what happens when that policy is ignored, as was the case in Spotsylvania?

For Kimberly Allen, this was a much bigger concern than the call to feed a fire with her collection. “I knew that this was just a way for people in our community to incite others and to try to get reactions,” says Allen, the school librarian at the district’s Post Oak Middle School and the county liaison for secondary librarians.

The larger issue was the complete disregard for the appropriate and established process.

In this case, a parent started it all by objecting to LGBTQ+ books in the district collection and specifically Call Me by Your Name by André Aciman. At a school board meeting, she read a summary of 33 Snowfish by Adam Rapp. The parent was not stopped and instructed to follow proper book challenge procedure. When she finished, two board members openly spoke about not just removing titles from the libraries, but burning the “offensive” books.

District librarians were tasked with putting specific terms into Destiny to find books with graphic sexual content. Those words included: sexually explicit, rape, pedophilia, prostitution, and graphic sex. Librarians had to cancel classes to complete this task.

“It was a nightmare,” says Allen.

The result: 140 books were identified as needing to be further reviewed per the criteria. None of those books were removed from circulation at the conclusion of the process.

Call Me by Your Name was removed from the collections of all district high schools without going through the reconsideration process, according to Allen. And as of that Dec. 13 board meeting, she says, there had been no official challenges filed at a school in the district.

Read: SLJ's censorship coverage

Not just Spotsylvania

Similar situations are occurring across the country. Within hours of SLJ setting up a new system for school librarians to share censorship attempts in their district, a half dozen librarians submitted their stories.

Only one reported having a policy that was being followed after a formal complaint. The others documented much different experiences: “Challenge policy was circumvented,” wrote one. Another reported being told to remove the books being questioned despite a reconsideration policy that clearly states books are not restricted while under review. Hundreds of books have been pulled from shelves for audits in one district. In another, parents asked for similar reviews of entire school collections.

Where librarians have the support of the school board and administration, objectors have been asked to fill out the paperwork for an official challenge.

In Allen’s case, a middle school parent wanted to speak with the principal, who told them they would need to have a conference with him and then submit the official reconsideration paperwork. Days later, the parent said they had changed their mind.

A librarian recounted a similar experience to SLJ: “Once the parent realized the book wouldn’t just be pulled on complaint, and that they would have to submit a formal, written challenge with their name attached, we have not heard anything since.”

At the Dec. 13 Spotsylvania board meeting, Allen reminded the board and community members of the official process.

“The next time someone wants to bring reading materials before the board, I would ask that you do what’s right and guide them to follow the policy and begin with the school principal,” Allen said. “You are the final level if needed in the process, not the first.”

After saying the board had become a “national embarrassment,” she continued, “This community needs you to step up and do what’s right for our students and staff in regards to respect, order, and conduct. This position isn’t about you, your five minutes of fame, catering to special groups, your opinions about state and federal politics or mask mandates. This office is about making sure our entire school system has everything needed to provide exemplary services to our students. At the end of the day, that is what is most important.”

Public libraries are now facing calls for books to be removed, too, after avoiding the fray for a while, even in Spotsylvania County.

Martha Hutzel, director of the Central Rappahannock Regional Library, which covers the city of Fredericksburg and Stafford, Spotsylvania, and Westmoreland counties, says branches have received complaints in the past, particularly about LGBTQ+ books on display during Pride Month.

“We listen to the complaints, and we say, ‘We’re a diverse society. We need diverse libraries. We have a diverse collection and that reflects our community. The books will be in the collection. They will be on display. You can choose not to check them out.’”

Hutzel has told staff at the library system’s 10 branches unequivocally where she stands on the issue.

“When the notion of book banning first came up in Spotsylvania County, where we have three branches, I wrote a letter to the editor of our local newspaper and I sent a very long, detailed email to all of my staff saying it’s wrong, it’s inappropriate, it’s censorship, it’s intolerable,” says Hutzel. “This is a First Amendment issue. This is contrary to ALA’s Freedom to Read [statement] and the Library Bill of Rights.”

Students speak out

She is heartened by what she has seen from young people in the community.

“Students have been phenomenal,” she says. “They have held rallies in front of at least one of their high schools against censorship and in support of keeping the books in the library.

“The idea that teens care that much about their school, and their books, and their library is astounding to me. It’s wonderful.”

In Central York, PA, and Kansas City, MO, these student protests and public support for the libraries and books have made a difference. In Spotsylvania County, it remains to be seen if it will matter. The controversy already created a ripple effect. The superintendent resigned at that Dec. 13 meeting, and the district’s librarians are now reconsidering how they handle collection development.

“We are in the process of revamping our policies and procedures for book selection and for weeding,” says Allen. “All of this has actually been beneficial in a lot of ways, because it really made us step back and take a hard look at where we are.”

They need more consistency, she says. Each librarian has their own set of beliefs, ranging from conservative to liberal, and the district needs a policy that creates consistent decisions among those with different perspectives. As part of this process toward a new collection development policy, they will examine age recommendations in reviews and how they are decided and ask district librarians to communicate more about the content of books they have read.

Will the librarians change how they make purchases to avoid a challenge

or controversy?

“Not necessarily,” Allen says.

She hopes librarians and teachers can build better relationships with parents to help alleviate their concerns. A lack of understanding and fear causes these issues, she says.

“Until we start figuring out ways to chisel [away at] that, and get back to some basic compassion and empathy and understanding of each other and why we have literature in the first place and why it’s important to make sure our kids are well-rounded and exposed to a variety of things to read,” she says, “this is just going to continue.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!