“[Slavery] should be taught but it might either be sugarcoated or too gory... and if it were to be sugarcoated then it might be too little of the truth,” wrote an astute seventh grader in a pre-thinking exercise related to a discussion on Emily Jenkins and Sophie Blackall’s controversial children’s book,

A Fine Dessert. Too little of the truth. It was an interesting phrase to use, especially for a book related to cooking. If telling the truth is a recipe, how does one measure what to include and when? Is there a responsible way to make hard truths palatable? Or must they stay raw and unprocessed? These are a few of the questions that sprang up in connection to Jenkins and Blackall’s book.

A Fine Dessert tells the story of blackberry fool being made by different families across four centuries in various, but mostly American, settings. The recipe serves as a narrative anchor for social and technological changes that take place as each generation’s parent-and-child duo prepares the treat. Its publication caused quite a stir because the author and illustrator chose to include an enslaved mother and daughter smiling twice during the process of creating the dessert for their masters in the section depicting 1810. Concerns were raised. Blogs and online articles noted that images of smiling slaves whitewash an ugly and brutal chapter of American history. Comments from readers also touched on how the depiction reinforces a

painful myth that some slaves were happy or led a comfortable life. As the dialogue grew in intensity, the

author apologized and the illustrator responded to criticisms on her blog. I found myself checking back in to read and reread comments. A few "

Reading While White" commentators voiced that they felt the book could hurt or shame children, and a commentator on Sophie Blackall’s blog referred to it as “depraved” and “dangerous” to use in a classroom. These stood out to me as an educator because I saw it differently. In this book, I saw an opportunity to invite my students—who are four to eight years older than the intended audience—into an important conversation on the representation of race and gender in children’s literature. I used the book this past December, a time when my entire school breaks from the usual classes and takes part in a program called “Intensives.” It’s a two-week course where the students focus solely on one project in order to deeply engage with a particular topic and skill. This year I designed a course for students to write and illustrate children’s books. The students I teach are in grades six through eight and are culturally diverse. The makeup of the whole school, grades six through 12, is 34 percent Asian, 43 percent Hispanic, six percent black, and 16 percent white. By bringing

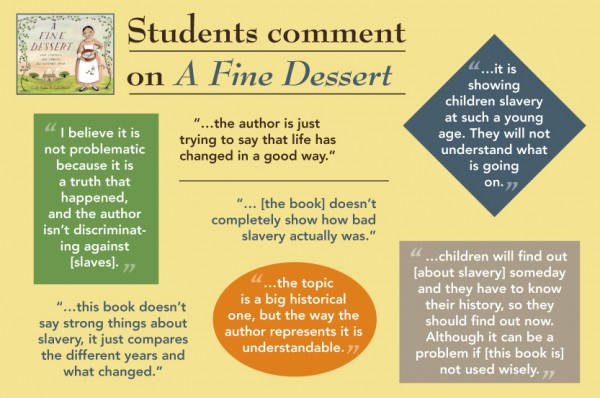

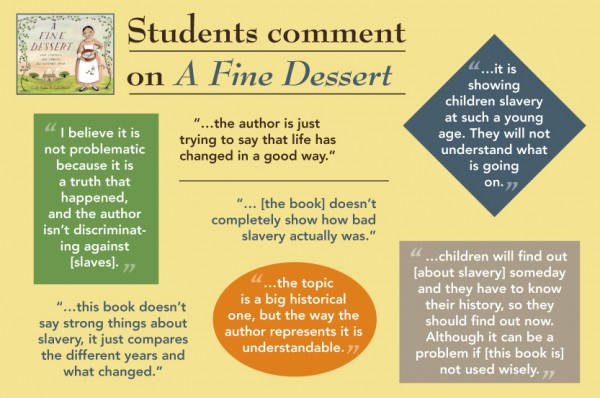

A Fine Dessert into the classroom, I gave students the chance to debate the issues surrounding the author's and illustrator’s choices, especially the images that caused controversy. The book was read aloud to the class. On each page, I prompted students with open-ended questions like “What do you observe on this page?” and then a few follow-ups such as “Why do those parts of the image stand out to you? What do they make you think?” Students were initially upset about how women were the only ones depicted working. When I got to the section on 1810, they remained upset about women again being in a position of servitude. When I asked my usual observation questions about the page where the daughter and mother are smiling, students spoke about how far away the characters were from the house and they commented that the mother and daughter were alone. During this first reading together, my students attributed their facial expressions to a mother-daughter moment. One student commented, “They seem happy to be away from the house.” After this group reading, they engaged in a student-run debate over whether the image was problematic and if the book should be taken out of the running for the Caldecott award. Then, I provided them with two book reviews: one that praised it and one that heavily critiqued it. I made sure to also include reader comments to those reviews as well. After the students read the articles, there was a noticeable shift. Some of the students who previously felt the smiles were merely nuanced images of joy between a parent and child were now moved by the hurt it caused and they sympathized with the outrage voiced in the comments. I asked them to transfer this knowledge to the work they would be doing both inside and outside the classroom on their own children's books and to think about what we see on TV shows, in ads, and in books and how these ideas can become ingrained in our minds as a stereotype of someone’s culture, religion, or gender.

Soon after the activity, a student conferenced with me, sharing that she decided not to make the stepmother in her book an evil character because that’s how stepmothers are always presented and she wanted her story to be different. Another student said that she looked more carefully at her story to make sure girls were not being shown as interested in just makeup and dolls. Like my students, I reflected on how the lessons of our discussion on

A Fine Dessert extend to other aspects of my work. In particular, I became more critical while examining the cover art of "The Bluford Series" books in my classroom library this spring. As I looked at them all together, a stereotype of urban life emerged that gave me pause. I decided to do a little research to see if others in the literary community have voiced this concern, and I discovered that the series creator, Paul Langan, spoke about the issue in

an interview with the New York Times. He shared that the popular series, credited with the aim of increasing literacy among struggling readers, was born out of a need for his students to see themselves in books and connect to an image that is like them. His personal experience struck me. It is the same heart and soul that fuels the campaign for diverse books. To close the achievement gap, it’s vital for historically marginalized students to connect to what they read, because books are like our friends. We feel at home and are comfortable with the ones most like us. After all, reading is an immensely personal act; the narrator’s voice echoes in our minds and has the power to make us feel less alone in the world. But I know, too, that in order to grow and mature beyond our own perspectives, we need to read books that aren’t simply mirrors of ourselves. As the conversation around diversity continues, I plan to continually reflect on the voices my students choose to hear as they select texts from my classroom library, to ensure they seek a broad array and to keep asking them hard questions about an author’s choices.

Soon after the activity, a student conferenced with me, sharing that she decided not to make the stepmother in her book an evil character because that’s how stepmothers are always presented and she wanted her story to be different. Another student said that she looked more carefully at her story to make sure girls were not being shown as interested in just makeup and dolls. Like my students, I reflected on how the lessons of our discussion on A Fine Dessert extend to other aspects of my work. In particular, I became more critical while examining the cover art of "The Bluford Series" books in my classroom library this spring. As I looked at them all together, a stereotype of urban life emerged that gave me pause. I decided to do a little research to see if others in the literary community have voiced this concern, and I discovered that the series creator, Paul Langan, spoke about the issue in an interview with the New York Times. He shared that the popular series, credited with the aim of increasing literacy among struggling readers, was born out of a need for his students to see themselves in books and connect to an image that is like them. His personal experience struck me. It is the same heart and soul that fuels the campaign for diverse books. To close the achievement gap, it’s vital for historically marginalized students to connect to what they read, because books are like our friends. We feel at home and are comfortable with the ones most like us. After all, reading is an immensely personal act; the narrator’s voice echoes in our minds and has the power to make us feel less alone in the world. But I know, too, that in order to grow and mature beyond our own perspectives, we need to read books that aren’t simply mirrors of ourselves. As the conversation around diversity continues, I plan to continually reflect on the voices my students choose to hear as they select texts from my classroom library, to ensure they seek a broad array and to keep asking them hard questions about an author’s choices.

Soon after the activity, a student conferenced with me, sharing that she decided not to make the stepmother in her book an evil character because that’s how stepmothers are always presented and she wanted her story to be different. Another student said that she looked more carefully at her story to make sure girls were not being shown as interested in just makeup and dolls. Like my students, I reflected on how the lessons of our discussion on A Fine Dessert extend to other aspects of my work. In particular, I became more critical while examining the cover art of "The Bluford Series" books in my classroom library this spring. As I looked at them all together, a stereotype of urban life emerged that gave me pause. I decided to do a little research to see if others in the literary community have voiced this concern, and I discovered that the series creator, Paul Langan, spoke about the issue in an interview with the New York Times. He shared that the popular series, credited with the aim of increasing literacy among struggling readers, was born out of a need for his students to see themselves in books and connect to an image that is like them. His personal experience struck me. It is the same heart and soul that fuels the campaign for diverse books. To close the achievement gap, it’s vital for historically marginalized students to connect to what they read, because books are like our friends. We feel at home and are comfortable with the ones most like us. After all, reading is an immensely personal act; the narrator’s voice echoes in our minds and has the power to make us feel less alone in the world. But I know, too, that in order to grow and mature beyond our own perspectives, we need to read books that aren’t simply mirrors of ourselves. As the conversation around diversity continues, I plan to continually reflect on the voices my students choose to hear as they select texts from my classroom library, to ensure they seek a broad array and to keep asking them hard questions about an author’s choices.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

A teacher and a parent

That's what I would have figured. If someone would do the research, I think they'd actually find that the vast majority of even American second (2nd) graders have some familiarity with the experience of African-American slavery, and know how oppressive it was. African-American children, even more so. (The same would be true for Chinese and Korean children about Japanese atrocities during World War II, Armenian children about the Turkish genocide, Jewish children about the Holocaust, Native American children about the westward genocide, and the abominable like). I think we all need to remember that kids learn as much outside our classroom as in it. Maybe more.Posted : Aug 24, 2016 12:38

Valerie

There is unit on slavery that is part of the fourth grade social studies scope and sequence. Not a single student was unaware. I gave them background before they read it and most students were in America for their elementary education (only one student was not).Posted : Aug 22, 2016 10:41

Valerie

Hi- Thank you for your comment! I really appreciate the feedback. Here is an old blog of mine: https://bookjacket.wordpress.com/ I have a post called "Offensive Narrators" that may be of interest.Posted : Aug 19, 2016 04:21

Amy

Love this idea -- what a great way to invite students to enter these terrific conversations that we are having! What review articles/blogs did you share? Can you link to them?Posted : Aug 18, 2016 12:41

A teacher and a parent

It is good to know that no children were harmed in the reading of this book. Imagine! More seriously, that the children focused on the gendering of the work is eye-opening. As I recall, this was not an issue raised in the discussions of A Fine Dessert last autumn. Just goes to show that it is easy to worry about all the wrong things, and that children's true concerns and foci may well be different from what we believe their concerns should be. Keep up the great teaching.Posted : Aug 17, 2016 07:10

richrobbob

It's refreshing to see that you can embrace controversy in your classroom and challenge students to, as you say, "read books that aren’t simply mirrors of ourselves". Kudos on finding a way to weave such a politically charged children's book into your Intensives. Your classroom experience and literary insights come together great here. Looking forward to future posts Valerie!!Posted : Aug 16, 2016 11:36

debraj11

Thank you for sharing this. The good: Some students recognized that being away from the house, which could be interpreted as away from the eyes of white masters, was a moment of calm, peace, even happiness. I wonder how much discussion there was about this? The interesting: Students identified issues regarding women and how they are depicted in the book. Some students used their critiques to interrogate their own projects. A true win for students and your leadership. The absent: How many students actually discussed slavery and why the images were problematic? Did students know that slave families were rarely intact. That a young girl working beside her mother was unlikely? Did they know that harsh punishments could have been meted out for stealing a bit of the master's dessert? Did they know that no loving mother would have risked such a punishment? Did they understand how false the sense of satisfaction displayed in the book would be from a lick? How sad a reward that was for the toil that went into preparing a meal to feed the people who enslaved you? Did they learn the difference between the status of slaves and the white indentured servants who worked beside them? These were the primary concerns with the representation of slaves in A Fine Dessert. I realize that you had limited space and provided the highlights from the activity. However, the reduction of the all the critiques of black representation in A Fine Dessert as "smiling slaves" provides little confidence that the exercise dealt adequately with any of them.Posted : Aug 16, 2016 08:17