2018 School Spending Survey Report

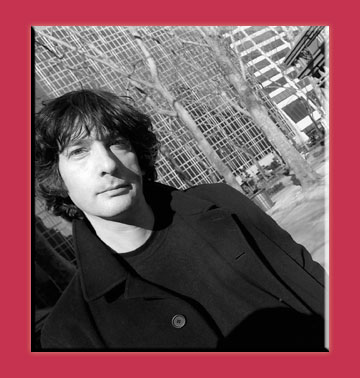

It's Good to Be Gaiman: A Revealing Interview with Newbery Winner Neil Gaiman

Neil Gaiman is on a roll. He’s nabbed the Newbery, walked the red carpet for Coraline, and then there’s that effing tweet.

Photograph by Kimberly Butler

Neil Gaiman has been a busy boy. I caught up with him by phone at his Wisconsin home, to which he had returned the night before from the film premiere of Coraline in Portland, OR. The movie hoopla, of course, was but a footnote to his Really Big News, winning the 2009 Newbery Medal for The Graveyard Book (HarperCollins, 2008). While SLJ had crowed that a popular book had won the Newbery for the first time in years, I was interested in something else: for the first time since forever, the Newbery went to a “celebrity author,” an acclaimed writer for adults whose hipness, in this case, was confirmed not only by the fact that Gaiman announced his Newbery news on Twitter, but also by just what he tweeted. Gaiman first gained wide notice as an author of comics, most notably “The Sandman” series (DC Comics), and confirmed his reputation as a major contemporary Anglo-American writer with the novels Stardust (1999), American Gods (2001), and Anansi Boys (2005, all William Morrow). But as Gaiman explains here, The Graveyard Book was begun many years before those titles, not as a children’s book, not as an adult book, but as simply a first page inspired by his son pedaling a tricycle through a cemetery near the family’s then-home in England. Roger Sutton (RS): Do you feel like re-creating your response after you found out you’d won the Newbery? Neil Gaiman (NG): Sure! Absolutely. RS: Too bad this isn’t a podcast. That was quite a tweet. NG: It was. If I’d really been thinking, I probably wouldn’t even have tweeted the tweet, not because, as far as I can tell, anybody actually got offended by it in the entire world, but because of the kind of people who like to intimate that there are controversies. RS: Which is what I felt about SLJ’s report—“Surprise! The Newbery Goes to a Popular Book.” NG: I thought SLJ had made this up, that people were saying, “Gaiman is a foul-mouthed yahoo!” I had just written a lengthy and well-considered blog entry, which, actually, was probably the only thing that kept me sane during the 40 minutes between getting the news I had won and being able to tell anybody. [Laughter] The Twitter just sort of went, “Waaaaaaaaaaaah! My God, I did it!” RS: I thought that SLJ report was… NG: I thought it was stupid. I’ve been reading the whole thing about what kind of book should win the Newbery with an interest that was not personal. I did not consider that The Graveyard Book would be in the running, or at least I figured that if it was, it would probably be in the top 30, if there was a top 30. It had not occurred to me that it was actually likely to be anything other than—if the gods smiled and the world was right—possibly a Newbery Honor Book. My favorite comment honestly was the one from the Guardian, where somebody in the U.K. just wrote an essay that said, “Well, you know, they’ve been arguing about whether the Newbery winner should be popular or whether it should be excellent, and they’ve got The Graveyard Book, which effectively demolishes the entire argument, because it’s both. So there.” RS: You’ve done comic books, children’s books, and adult fiction, and they always seem to be concerned with the borders between the real and the unreal. NG: I think that’s very fair. There are definitely things that become thematic in retrospect. I, of course, didn’t know this when I started out, and I was mostly concerned with making sure the next thing I did wasn’t like the last thing I had done. But there’s always this very peculiar point where you look back and start noticing weird little thematic quirks that definitely weren’t planned. RS: It seems like you’re always asking the question, “Am I dreaming? Am I awake?” NG: That’s definitely a huge part of it. Or, really, is this real? And how would I know if this were real? And what do you do if this is real? RS: Mm-hm. NG: I was in Bologna a few years ago, in 2003, listening to a speech being given at the university about my work. It was an incredibly perceptive speech by a Bolognese professor of children’s literature. What fascinated me and troubled and worried me was I thought that I was so clever. I thought that everything I did was so different. And in this speech, the lady was talking about what it is that I’ve done, what it is that I do. And I realized with a sort of horrible sinking feeling that she was describing my next two books. [Laughter] She was describing Anansi Boys, and she was describing The Graveyard Book. And it was a really major sinking feeling. It was like, Oh, my God. I’m actually doing the same thing over and over. But with The Graveyard Book, there was also—I’ve told this anecdote several times, and I should probably tell it here, just because it does give the book context, and also it’s true. RS: Plus, I don’t know that I’ve heard it. NG: The Graveyard Book was the longest in gestation of anything I’ve done. And it also was kind of the book that I was working towards writing for a very long time. It began in 1986, maybe early ’87. We were living in a very, very tall house in Suffolk, in which pretty much every room was on a different floor. I had a two-year-old son, and more than anything in the world, he loved his tricycle. And we didn’t have any kind of yard, and he really couldn’t ride the tricycle in the house because he would die. So I would take him every day with his tricycle to the graveyard across the road, in this old churchyard. And he would pedal happily up and down the paths between the graves. And I would sit in the sun and read a book and look at him and smile. At some point, I just remember looking at him and thinking how incredibly at home he looked. And then I thought, you know, you could write something like The Jungle Book and set it in a graveyard. And it was just this lovely little nice clean thought. And then I thought you’d call it The Graveyard Book. And you’d have dead people bringing him up, and probably in the Bagheera role I’d have a vampire and maybe a werewolf as Baloo. And it just sort of clicked. It felt right. That evening I went up to my study, and I sat down. I was a working journalist at this point. I’d written a few short stories. And I wrote an attempted first page and then read what I’d written and thought, You know, I’m not good enough for this. This is a really good idea, and it’s much better than I am as a writer. I will put it aside until I’m good enough. And once, maybe twice after that in the intervening years, I would go back and try writing a bit more. I’d definitely given up on it by 1989. RS: Was it a children’s book all along in your head? NG: Well, it was always whatever it is. Somewhere in 2004, after I’d finished writing Anansi Boys, it occurred to me that technically I was no longer getting better in terms of, you know, just the sheer skill of putting a sentence together, the ability to say whatever it was that I wanted to say. Whether I was any good or not, I didn’t know. But I was definitely no longer seeing the kinds of year-to-year improvement that I had previously been aware of. I was now going, “OK, this is basically whoever I am.” And I no longer had any excuse for putting off writing the story. I had a notebook with the words, “There was a hand in the darkness, and it held a knife.” That was definitely going to be the first line. I had begun and given up on the opening many times, and suddenly I thought, I can start in the middle. So I did. I wrote one page. We were on Christmas holiday in Antigua. I don’t do holidays terribly well, because I get really bored after a day or two. I catch up on sleep. I don’t do anything for a couple of glorious days, and by day three, it turns into hell. RS: I just like to read. NG: So I pulled out my little notebook, and I started to write. My daughter Maddy came back from splashing around in the sea and sat on the deck chair next to me and said, “What are you writing?” And I said, “Oh, I’m writing a story, but I don’t think it’s any good. I’m about to stop.” She said, “Well, read me what you’ve done so far.” So I read her the first page and a half of “The Witch’s Headstone,” and I got to a point where it petered out. She looked at me and said, “What happens next?” And it is those three words that keep writers going. RS: And just look at where those three words brought you this time. Have you ever been to an ALA awards banquet? NG: I’m pretty sure that I was at one in Atlanta. RS: But at this one, you’ll have to eat up on a podium. NG: I’m looking forward to that. It’ll be fun. I was informed that I am a Newbery laureate, which I love. I feel as if one wants to parade around in one’s toga, but it’s much too cold. RS: What are you going to wear? NG: I think it’ll probably be something black—on the basis that I don’t have any clothes that are any other color. Probably black jeans, black T-shirt, and probably not a leather jacket. I’ve decided that as I chug into my 50s, I should start investigating other sorts of clothing than leather jackets. RS: It is dinner. There will be ladies in gowns. NG: I always like seeing ladies in gowns, especially librarians. Librarians know how to wear gowns.Roger Sutton, longtime editor-in-chief of The Horn Book, plans to wear a bow tie to ALA’s upcoming awards banquet. It will not be a clip-on.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!