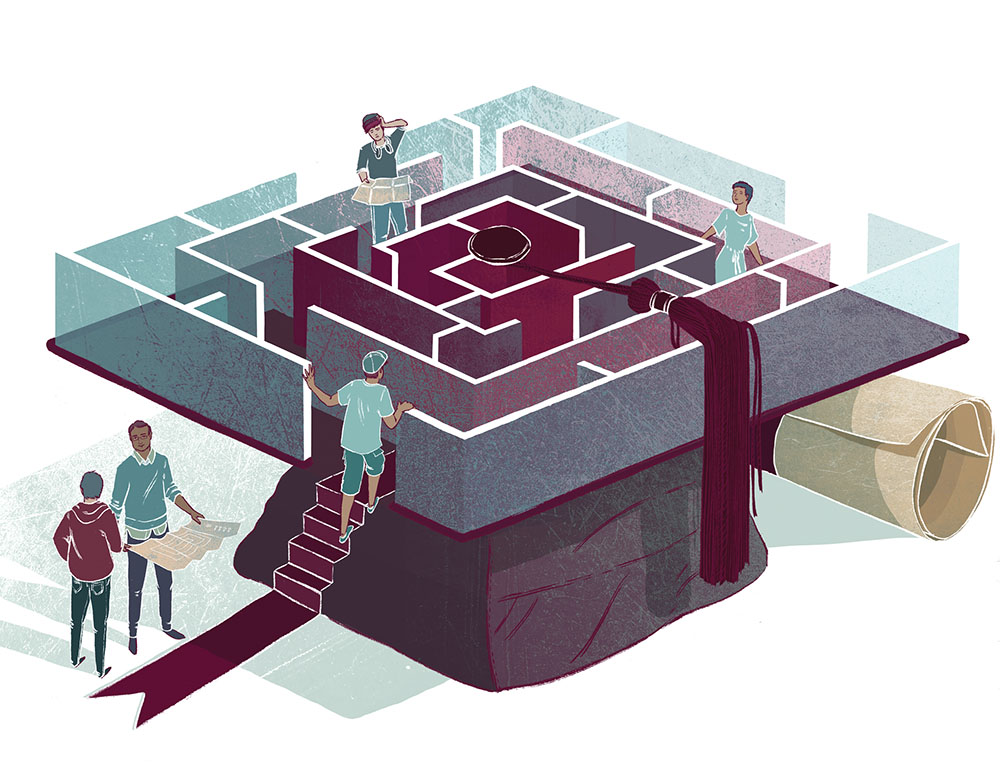

Higher Ground: Getting College Ready in the Library

Illustration by Cat O'Neil

When Trameka Pope was a senior in high school, she wasn’t sure that she wanted to leave home for college. Statistically, it was unlikely that Pope—whose daughter was a baby at the time—would go to college at all, much less successfully navigate the academics once there. She not only got there, however, she finished her bachelor’s degree in public health at Western Illinois University in three years and is applying for a master’s program.

At Wendell Phillips Academy on Chicago’s South Side, Pope found the critical support she needed at the daily college readiness class offered by the high school’s librarian, K.C. Boyd, who also researched many of the scholarships that made it financially feasible for Pope to go to school.

“She was really there for me,” Pope says of Boyd, “especially when I was trying to decide how far to go because I had a daughter.”

From specialized scholarships to budgeting for book fees, Boyd gave her students the information they needed to succeed. It was information Pope would later learn many others weren’t getting.

“The way that she pushed our class with college information and making sure we were prepared, my friends I met in college didn’t have that,” says Pope.

Boyd, a Library Journal Mover & Shaker, is now a library media specialist at a Washington, DC, public middle school. Her college readiness efforts at the Chicago high school were part of a larger phenomenon of librarians working alongside guidance counselors to help students not only get to college but thrive once they are there. Librarians have long offered resources, such as SAT prep materials and college guidebooks. But today, many are doing much more, helping students through the increasingly byzantine process of selecting, applying to, getting aid for, preparing for, and persevering in college.

That process is particularly onerous for low-income students, 68 percent of whom enroll in two- or four-year college after high school, according to the National Center for Educational Statistics, compared to 83 percent of high-income students. Only 14 percent of low-income students receive a bachelor’s degree, compared to 60 percent of high-income students.

Librarians are crucial contributors to college readiness in schools strapped for resources, which makes it even more painful that librarians are being cut in many of those districts and schools. There are 19 percent fewer librarians in schools today than in 2000, and schools serving majority minority students have lost the most, according to SLJ research.

Help with essays, résumés, and scholarships

In Bensalem, PA, where 47 percent of students are low-income, Bensalem High School librarian Tiffany Emerick tries to make the college application process low-stress but comprehensive. To start the conversation, she’ll ask students about their postgraduation plans. Many of these teens start working or join the military after graduation. But if they mention college, that’s “the gateway,” Emerick says, to offering more support toward that goal.

Some students ask her to read essays. Others use library resources to scan documents for financial aid forms or register for the SAT, because they don’t always have Internet access at home. Last year, a student whose essay Emerick had helped edit presented her with a card: “I couldn’t have gotten into my dream school without you,” it said. The school was Stanford University.

School librarians often work alongside guidance departments for college applications and preparation, but in schools such as Emerick’s, the ratio of students to counselors can be 400 to 1. In some schools, that ratio balloons to 2,000 to 1, says Sandra Hughes-Hassell, professor at the School of Library and Information Science at the University of North Carolina and president of the Young Adult Librarian Services Association (YALSA).

“I love my guidance department, but I can’t guarantee that they have the time [to help]. I do,” says Susan Altman, a librarian at Eau Claire High School in Columbia, SC. Many of her students would be first-generation college students, she says, and she tries to provide support by reading over personal statements, helping with résumé creation, and researching schools and scholarships. “There may be an obscure program out there that may have a great opportunity for our students that they may otherwise not know about.”

The number of librarians taking on these informal duties in some cases comes down to district economics. In less well funded or less affluent districts, librarians often pitch in with every aspect of the college planning process, as guidance departments may be squeezed by low staffing and a need to focus on career planning and working with students who have experienced trauma.

“I would say it’s what librarians do naturally—which is being open to anyone in need and offering resources, opening conversations, and saying, ‘Can I help you at all?’” says Emerick. “Some [students] are comfortable coming for help but not everyone is, especially if they are new or don’t have adults they trust. The librarian can have that role—I’m not giving them a grade, I’m just here to help.”

At Williamsport Township (PA) High School (WTHS), students can find librarian Kimberly Brosan’s extensive libguide on applying to college, with subsections on testing, applications, choosing a school, and paying for higher education. She developed the guide after talking with her guidance department and seeing where she could step in.

Earlier preparation, maker portfolios

Librarians also prepare students for college, of course, by getting them ready for college-level work. Williamsport has a strong career and technical education program, and many students participate in dual-enrollment classes with nearby Penn College of Technology. Brosan helps them with college-level research while they are still in high school. Nearly half of students from the school eventually enroll in college, and 51 percent of WTHS students are low-income.

“There are lots of youth in small, rural, and tribal areas that don’t have access in their school to college- and career-ready resources,” says Hughes-Hassell. “There are ways we can support kids to think about the college and career process that are more than at that application time or writing the college essay.”

To that end, YALSA launched its Future Ready program two years ago (ala.org/yalsa/future-ready-library). It takes a step back and starts preparation even earlier—in middle school—through partnerships with school and local libraries that encourage college readiness.

In Bolivar, TN, for instance, Bolivar-Hardeman County Library director Baillee Hutchinson is using a Future Ready grant to go into schools and meet with teens. Meanwhile, in Charlotte-Mecklenburg, NC, the local library system partners with schools to offer College 101 workshops and has organized a post secondary trade school fair, says Hughes-Hassell.

In affluent districts, however, children are often coached on college options from the time they are very young, and high schools may have dedicated college counselors within the guidance department. In these districts, the librarian might focus more on college-level research skills, such as citation and bibliography formats and seeking credible sources.

“They do so much of this at home,” says Michelle Luhtala, librarian at New Canaan (CT) High School (NCHS). Ironically, she says, “one of the things I try to do is not talk to the kids about where they are [in the college process], because there are so many pressures and constraints that it is onerous. We try to give them diversions and stress release instead.”

At NCHS, the virtual reality lab in the library’s makerspace is in use all day, says Luhtala. Here, students are developing skills and products they might use to apply to college. “They come in to slice things in half then we have classes that use it for anatomy and immerse themselves in pulling skeletons and the body apart and reassembling it.” Nearly half of high schools surveyed recently by SLJ host makerspaces in their libraries.

The experience of making can be profound for students of all backgrounds—and maker immersion is something that some students showcase in their applications. While colleges overall say portfolios are less important than other factors, some, including MIT, Tufts, and Carnegie Mellon, consider “maker portfolios” by students interested in computer science or engineering, according to the 2017 State of College Admissions report from the National Association for College Admission Counseling.

Former NCHS student Miles Turpin received his Duke University acceptance letter with a comment that the admissions committee noted his interest in makerspaces. Photo courtesy of Michelle Luhtala

Former NCHS student Miles Turpin received his Duke University acceptance letter with a comment that the admissions committee noted his interest in makerspaces. Turpin had included a link to his website with a portfolio and written about his experience initiating a program for students to get credit for makerspace projects. “I felt like I did something meaningful that lasted,” he says of both his maker projects and the program he created for students after him.

“So many [students] find that home with the maker mentality,” says Heather Moorefield-Lang, associate professor of library science at the University of South Carolina and a technology specialist. “It gives them a new focus whether they want to do circuitry or arts, music, culinary, or farming. It opens a whole new door or opportunity.”

Still, makerspaces require funding, and when librarians are cut, fewer will be able to double as digital stewards in schools. In Williamsport Township next year, Brosan will split her time between the middle school and high school. She asked her high school students how the change might impact them, and they singled out her instruction on how to use databases and their need to learn how to do research. But Brosan sees a silver lining. Their experience with her has taught them there is another person they can seek out for help soon: the college librarian.

Carly Berwick is a freelance journalist and English teacher in New Jersey.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!