Gender by the numbers

A poster in our office lobby for the upcoming Simmons International Women’s Film Forum alerted me to the interestingly low–29%–number of female protagonists in films for children.* I guess it ain’t all Disney Princesses after all. How does this compare with the numbers in books for children? I asked myself. The gender disparity had been on my […]

The post Gender by the numbers appeared first on The Horn Book.

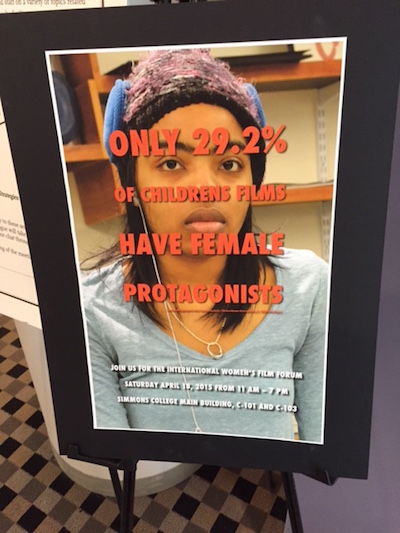

A poster in our office lobby for the upcoming Simmons International Women’s Film Forum alerted me to the interestingly low–29%–number of female protagonists in films for children.* I guess it ain’t all Disney Princesses after all.

A poster in our office lobby for the upcoming Simmons International Women’s Film Forum alerted me to the interestingly low–29%–number of female protagonists in films for children.* I guess it ain’t all Disney Princesses after all.

How does this compare with the numbers in books for children? I asked myself. The gender disparity had been on my mind ever since I got sucked into the Bookriot discussion about girls and YA spurred by the Andrew Smith drama of a couple of weeks ago. Somebody on the thread was vociferously decrying the lack of female protagonists in YA novels, which made me think what you all are probably thinking: Wait, wut?

But the poster and the discussion made me think it was a good time to do some arithmetic. Or, more precisely, engage our talented Emerson College intern Mariesa Negosanti in researching the question of gender representation in youth fiction via our ever-handy Horn Book Guide.

Our sample was limited to the Fall 2014 issue of the Guide, which reviewed all hardcover books published in the first six months of 2014 by U.S. publishers listed in LMP. Mariesa coded each fiction review in the Intermediate and Older Fiction sections for gender of protagonist(s): male, female, both, neither. The numbers for Older (books for 12-18-year-olds) were not surprising, except maybe to that zealot at Bookriot: 65% of the protagonists in YA novels were female, 22% were male, boys and girls shared main-character duties in 13%. I thought the numbers for Intermediate (roughly 9-12-year-olds) would be about the same but NO: 48% boys, 36% girls, 16% both.

I’m guessing the greater numbers of boy-heroes in fiction for these younger readers is probably attributable to our conventional wisdom that pre-teen girls are more likely to read about boys than the other way around, so a book about a boy is more likely to garner more readers. And that–conventional wisdom again–teen boys are less likely to read for pleasure than teen girls are, period, and that those boys who do read tend to prefer nonfiction.

Down at the other end of the age spectrum, we’ve been thinking about gender from a completely different angle: is it fair to label as male or female a character in a wordless picture book? Because, who knows?

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!