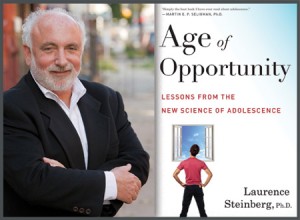

Gaming the Teenage Brain: Q&A With Social Scientist Laurence Steinberg

Laurence Steinberg is a distinguished university professor of psychology at Temple University and author of Age of Opportunity: Lessons from the New Science of Adolescence (HMH, 2014). Angela Carstensen, for SLJ, spoke with Steinberg about brain plasticity, risk taking, and reimagining high school.

Laurence Steinberg is a distinguished university professor of psychology at Temple University and author of Age of Opportunity: Lessons from the New Science of Adolescence (HMH, 2014). Angela Carstensen, for SLJ, spoke with Steinberg about brain plasticity, risk taking, and reimagining high school.

SLJ: You state that adolescence extends from around 10 to 25, and that one hallmark of the period is brain plasticity nearly matching that of early childhood. This lends teens vulnerability to harm—and a unique opportunity to thrive and learn. How might educators take advantage of this?

LS: The part of the brain that is especially plastic in adolescence is a region that responds well to novelty and challenge. I think the most important thing that educators can do is to provide opportunities for adolescents to learn new things and push themselves to think and work harder than they’ve done in the past.

Teens are known for risky behavior and taking more chances when with peers. But peer pressure isn’t the problem, you say, nor is feeling invulnerable or a lack of understanding consequences. What are your findings concerning the heightened sensitivity to reward?

Brain systems that respond to reward, and that create the experience of pleasure, are more easily aroused in adolescence than before or after. This super-sensitivity to reward leads teenagers to go after exciting or novel experiences—what psychologists call “sensation seeking”—even when there are potential dangers in doing so. Being around peers seems to exacerbate this phenomenon, we think, because being with peers is especially rewarding in adolescence.

You conclude that keeping teens out of harm’s way is key, especially finding productive activities after school. How can librarians and other educators protect the teens in their care?

Much of the risky behavior that adolescents engage in occurs during the late afternoon hours—when school is over but before parents have returned from work. Keeping school libraries and other facilities open during this time, and using these settings as places to provide interesting and enjoyable after-school activities, may help reduce risky behavior by keeping students in structured and supervised activities.

How does social media affect the frequency of peer-influenced risky behavior?

A lot of the risky media use that teenagers engage in is stimulated by the fact that their peers are “present” much of the time. We’ve shown that just making teenagers think that people their age are observing them (when in fact they aren’t) increases risky behavior. No one has studied this in the context of social media yet, but it’s an obvious thing to look at.

You’ve found that developing a peer culture that respects academic achievement is the missing element in American high schools.

America has always had a strong anti-intellectual culture, and I doubt there’s much we can do about that. But we can certainly make high school more challenging and interesting. American adolescents rank near the top of the world’s teenagers in their ratings of how boring high school is.

You highlight the impact of stress in several contexts, from increasing the likelihood of early puberty to increasing risky behavior in otherwise more mature kids in their late teens. What can mitigate teen stress?

Some of the stress teenagers are under comes from schools assigning far too much homework. Many educators have confused the quantity of the homework they assign with the degree of challenge it provides. Piling on repetitious assignments places teenagers under stress, because of the time it occupies, without really benefitting them intellectually. Another significant source of stress for many adolescents is school sports. Teenagers need plenty of exercise, but they don’t need to be stressed out by competition. There are also things teenagers can do to cope more effectively with stress. Getting enough sleep—between eight and nine hours each night—is very important.

You also discuss the need for “reimagining high school” to teach perseverance, determination, and self-control, all elements of “self-regulation,” in order to improve student achievement. Have any of these teaching methods been tested?

The one approach that has been tested the most is mindfulness, which can be taught through meditation, yoga, and martial arts. Schools ought to be incorporating these activities into their curricula.

Angela Carstensen is head librarian at Convent of the Sacred Heart school in New York City.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Freddie

Purchasing goods you don't require is clumsy and it is not just a wise way to employ coupons.Posted : Mar 24, 2016 09:35