A Brief History of Zines

Self-publishing by marginalized people has always taken place outside the mainstream, even before the word zine existed.

|

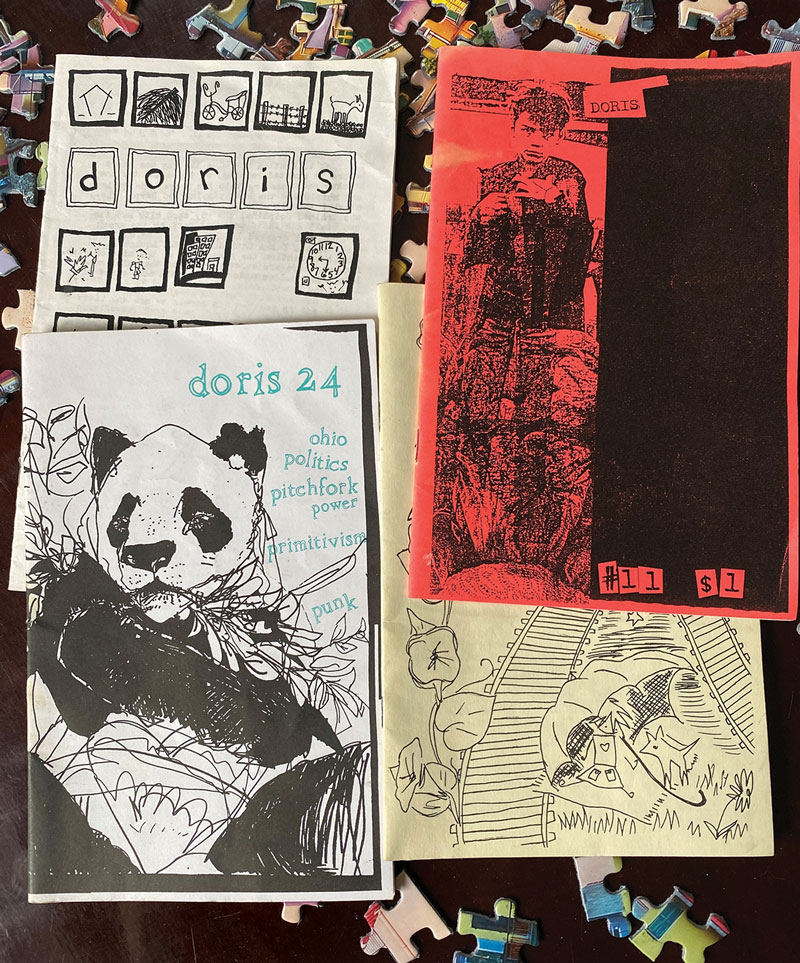

A few issues of Cindy Crabb’s DorisCourtesy of Cindy Crabb |

Self-publishing and small publishing by marginalized people have always taken place outside of the mainstream, even before the word zine existed. Examples include Ben Franklin’s Almanac, scrapbooking by Victorian women, and pamphlets and fliers supporting Cesar Chavez’s grape boycott.

In the 1930s and 1940s, science fiction fans created the first fanzines, small self-published magazines, sharing stories, poems, and art about science fiction they loved, which were traded at science fiction conventions (an earlier version of fan fiction). In the 1970s, another fringe group—punks—used the concept of the fanzine to share info about their music. Punks coined the word zine and connected publishing with DIY culture.

In the 1980s and 1990s, self-publishing took off with the growth of photocopying technology and of copy shops like Kinko’s, providing access to inexpensive copy machines. The 1990s also supported the rise of perzines (personal zines), which, like diaries or blogs, share one person’s thoughts and opinions.

Also read: "Zines: Cut-and-Paste Publishing by and for the People"

Two long-running zines, Cindy Crabb’s Doris (1993) and Aaron Cometbus’s punk zine Cometbus (1981), set examples of how autobiography could work as serials. Review zines like Factsheet Five (1982), Global Mail (1990s), and Action Girl Newsletter (1992) shared zine reviews and created networks for zinesters to find each other. Before the internet, many folks relied on zines to network. Queercore zines like J.D.s (1985) and Homocore (1988) inspired AIDS activism, increased positive queer visibility, and shared events at a time when homophobia was rampant.

In the 1990s and into the 2000s, the riot grrrl movement in the Pacific Northwest emphasized activism and feminism. BIPOC zines like Mimi Thi Nguyen’s Evolution of a Race Riot, Osa Atoe’s Shotgun Seamstress, and Eric Nakamura and Martin Wong’s Giant Robot pushed for representation and voice in the mostly white zine landscape.

The 1990s also saw distros, small distribution centers, disseminating zines at concerts and via the mail. Then, the option of home computers and printing meant zine publishing could happen anywhere. The 2000s brought a rise of disability, health, and mental health zines like E.T. Russian’s Ring of Fire, Ben Holtzman’s Sick: A Compilation Zine on Physical Illness, and works by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha.

While blogs and online zines provide faster ways to connect, paper zines endure, offering a hands-on, creative alternative to screen time.

Cathy Camper is an artist, librarian, zine creator, and author of books for children and teens.

|

Related ArticlesZines: Cut-and-Paste Publishing by and for the People 9 Books about Zines for Teens and Tweens |

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!