2018 School Spending Survey Report

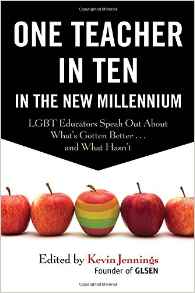

"One Teacher in 10 in the New Millennium: LGBT Educators Speak Out" | Professional Shelf

"Today, in 2015, teachers can be fired in 29 states because of their sexual orientation and in 32 states because of their gender identity."

“No type of community has a monopoly on tolerance and none has a monopoly on bigotry.”

When Kevin Jennings, founder of the Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network (GLSEN) and current Executive Director of the Arcus Foundation, first published One Teacher in 10: Gay and Lesbian Educators Tell Their Stories (Alyson Publications) in 1994, he provided a forum for LGBT educators, many of whom felt the need to hide their personal lives, whether newly employed or experienced, respected administrators. In the preface to the book Jennings wrote, “Only through telling our stories can we shatter the myths and expose the lies that allow bigots to portray us as a threatening ‘other.’” A second edition, published in 2004, reflected shifting attitudes among and about LGBT teachers, and the most recent compilation, One Teacher in Ten in the New Millennium (Beacon, 2015), includes contributions from across the United States as well as South Africa, Holland, and China. And notably, in a profession dominated by women, a good number of strong, proud female voices are clearly heard. Still, despite recent advances, such as the Supreme Court’s landmark decision affirming the constitutionality of same-sex marriage and the burgeoning recognition and acceptance of the transgender movement, many LGBT teachers and students know all too well that not all schools are safe and welcoming. Kevin Jennings speaks to this as he answers questions about his book and the road ahead. What first prompted you to gather personal narratives from LGBT teachers? I had an awful time in school myself, being bullied severely as I was perceived to be gay, and eventually attempting suicide my junior year in 1980. When I became a teacher, I saw my own LGBT students struggling and felt I needed to come out as gay to give them hope for their futures. I did this in 1988, during a very different time, when only one state had a law protecting teachers from being fired because of their sexual orientation. It was incredibly scary because I had no role models. I decided to create One Teacher in Ten to share educators’ stories and to encourage more LGBT teachers to be open and honest about themselves. How did you find contributors? First I asked people I knew. Then I asked organizations such as the National Black Justice Coalition to do targeted outreach to their members who were teachers. And finally, I just put the word out over the Internet that I was accepting submissions. The final product is about equally divided between contributors I found using these three methods. Why publish a new collection now? What major differences stand out for you in contributors’ stories 20 years later? One major difference is the diversity of this collection. The original 20-plus stories included no contributions from transgender educators, any from outside the United States, and only one from a person of color. By contrast, more than 50 percent of the contributors to this new collection are people of color, from outside the US, and/or transgender. I am happy that it reflects more of the diversity within the LGBT community. In the original 1994 edition, many contributors were closeted or, if they were out, they still felt compelled to use pseudonyms or to disguise the locations of their schools. I figured that I’d be getting more positive stories this time, but was curious to see if things had changed as much as people seem to think they have. There were indeed many positive stories, but there were still many that showed how challenging it is to be an out LGBT teacher. In the introduction, you point out, contrary to expectations, some teachers who work in locations with reputations for tolerance—New York City, Portland, Oregon, and the Netherlands, for example—hesitate about coming out and others have encountered resistance as openly gay teachers. What do you make of this? This was probably the biggest surprise for me. I figured the more negative experiences would be found in regions stereotyped as being bigoted, not in places like Oregon, which has an openly bisexual governor! What I learned is complicated, but can be summed in this way: laws are necessary but insufficient when it comes to guaranteeing equality. I say necessary because, in cases such as Duran Renkema’s in the Netherlands, it was vital that his country had a law that forbade discrimination based on sexual orientation, as it enabled him to save his job when bigots tried to fire him. The United States does not have such a law. Today, in 2015, teachers can be fired in 29 states because of their sexual orientation and in 32 states because of their gender identity. But despite the presence of laws [that protect teachers in some states] teachers still struggle for acceptance in places like Oregon and New York. That made it clear to me that we need to change peoples’ attitudes—their hearts and minds—as well as laws. We have a long way to go. Fortunately, stereotypes about homophobia in rural and suburban communities aren’t always true. When talking about the ease with which she and her wife and family are accepted by their community, one contributor writes, “it is nice to blend.” Yes, people tend to think LGBT people are concentrated in big cities, but in this collection we find contributors coming from not only urban but also suburban and rural communities, and telling hopeful stories about their experiences there. No type of community has a monopoly on tolerance and none has a monopoly on bigotry. Most of the contributors write about the freedom that comes from letting students and fellow teachers into the simple truths of their personal lives. Can you comment on how deciding to stay closeted might impact a teacher’s professional effectiveness? It can’t help but hurt. All the time and energy you put into hiding who you are is time and energy you could put into being a better teacher. What can/should schools do to foster acceptance of gay teachers? Any suggestions for teacher training programs? First we need legislative action to make sure that teachers are protected from job discrimination and know they’ll be judged based on their effectiveness and not their sexual orientation or gender identity. But, as I have said above, those laws are necessary but will be insufficient if that's all we do. We need to make sure that every educator is trained on the unique needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth and is able to meet those needs. Surveys show that seven percent of American high school students identify as LGBT (or, 1 in 14), meaning that statistically it's highly unlikely most classes don’t have at least one LGBT student. Teacher prep and professional development programs need to equip teachers to be able to serve those students effectively.

When Kevin Jennings, founder of the Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network (GLSEN) and current Executive Director of the Arcus Foundation, first published One Teacher in 10: Gay and Lesbian Educators Tell Their Stories (Alyson Publications) in 1994, he provided a forum for LGBT educators, many of whom felt the need to hide their personal lives, whether newly employed or experienced, respected administrators. In the preface to the book Jennings wrote, “Only through telling our stories can we shatter the myths and expose the lies that allow bigots to portray us as a threatening ‘other.’” A second edition, published in 2004, reflected shifting attitudes among and about LGBT teachers, and the most recent compilation, One Teacher in Ten in the New Millennium (Beacon, 2015), includes contributions from across the United States as well as South Africa, Holland, and China. And notably, in a profession dominated by women, a good number of strong, proud female voices are clearly heard. Still, despite recent advances, such as the Supreme Court’s landmark decision affirming the constitutionality of same-sex marriage and the burgeoning recognition and acceptance of the transgender movement, many LGBT teachers and students know all too well that not all schools are safe and welcoming. Kevin Jennings speaks to this as he answers questions about his book and the road ahead. What first prompted you to gather personal narratives from LGBT teachers? I had an awful time in school myself, being bullied severely as I was perceived to be gay, and eventually attempting suicide my junior year in 1980. When I became a teacher, I saw my own LGBT students struggling and felt I needed to come out as gay to give them hope for their futures. I did this in 1988, during a very different time, when only one state had a law protecting teachers from being fired because of their sexual orientation. It was incredibly scary because I had no role models. I decided to create One Teacher in Ten to share educators’ stories and to encourage more LGBT teachers to be open and honest about themselves. How did you find contributors? First I asked people I knew. Then I asked organizations such as the National Black Justice Coalition to do targeted outreach to their members who were teachers. And finally, I just put the word out over the Internet that I was accepting submissions. The final product is about equally divided between contributors I found using these three methods. Why publish a new collection now? What major differences stand out for you in contributors’ stories 20 years later? One major difference is the diversity of this collection. The original 20-plus stories included no contributions from transgender educators, any from outside the United States, and only one from a person of color. By contrast, more than 50 percent of the contributors to this new collection are people of color, from outside the US, and/or transgender. I am happy that it reflects more of the diversity within the LGBT community. In the original 1994 edition, many contributors were closeted or, if they were out, they still felt compelled to use pseudonyms or to disguise the locations of their schools. I figured that I’d be getting more positive stories this time, but was curious to see if things had changed as much as people seem to think they have. There were indeed many positive stories, but there were still many that showed how challenging it is to be an out LGBT teacher. In the introduction, you point out, contrary to expectations, some teachers who work in locations with reputations for tolerance—New York City, Portland, Oregon, and the Netherlands, for example—hesitate about coming out and others have encountered resistance as openly gay teachers. What do you make of this? This was probably the biggest surprise for me. I figured the more negative experiences would be found in regions stereotyped as being bigoted, not in places like Oregon, which has an openly bisexual governor! What I learned is complicated, but can be summed in this way: laws are necessary but insufficient when it comes to guaranteeing equality. I say necessary because, in cases such as Duran Renkema’s in the Netherlands, it was vital that his country had a law that forbade discrimination based on sexual orientation, as it enabled him to save his job when bigots tried to fire him. The United States does not have such a law. Today, in 2015, teachers can be fired in 29 states because of their sexual orientation and in 32 states because of their gender identity. But despite the presence of laws [that protect teachers in some states] teachers still struggle for acceptance in places like Oregon and New York. That made it clear to me that we need to change peoples’ attitudes—their hearts and minds—as well as laws. We have a long way to go. Fortunately, stereotypes about homophobia in rural and suburban communities aren’t always true. When talking about the ease with which she and her wife and family are accepted by their community, one contributor writes, “it is nice to blend.” Yes, people tend to think LGBT people are concentrated in big cities, but in this collection we find contributors coming from not only urban but also suburban and rural communities, and telling hopeful stories about their experiences there. No type of community has a monopoly on tolerance and none has a monopoly on bigotry. Most of the contributors write about the freedom that comes from letting students and fellow teachers into the simple truths of their personal lives. Can you comment on how deciding to stay closeted might impact a teacher’s professional effectiveness? It can’t help but hurt. All the time and energy you put into hiding who you are is time and energy you could put into being a better teacher. What can/should schools do to foster acceptance of gay teachers? Any suggestions for teacher training programs? First we need legislative action to make sure that teachers are protected from job discrimination and know they’ll be judged based on their effectiveness and not their sexual orientation or gender identity. But, as I have said above, those laws are necessary but will be insufficient if that's all we do. We need to make sure that every educator is trained on the unique needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth and is able to meet those needs. Surveys show that seven percent of American high school students identify as LGBT (or, 1 in 14), meaning that statistically it's highly unlikely most classes don’t have at least one LGBT student. Teacher prep and professional development programs need to equip teachers to be able to serve those students effectively. RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!