Legislating Classroom Conversation: What Do the "Anti-Critical Race Theory" Laws Mean for Teachers?

For many educators returning to schools this fall, classroom discussion will be governed by controversial provisions in a proliferation of legislation.

|

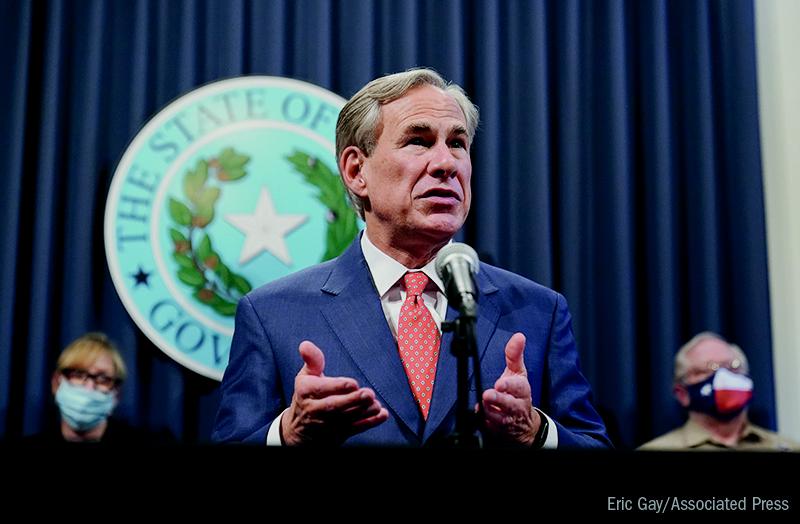

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott is one of many governors across the country who have signed laws limiting what U.S. history and current events can be taught in schools. |

In the months leading into this new school year, many states, including Idaho, Iowa, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Texas, have enacted laws to curtail a range of public school teaching activities concerning race, racism, and equality.

These laws are purportedly aimed at critical race theory—a legal framework formulated in the 1970s through which scholars, educators, community leaders, etc., can view race and systemic racism in the United States.

Critical race theory (CRT) considers foundations of equality, race, and racism against historical, economic, and legal backdrops and embraces core tenets that stem from an overarching notion that racism is embedding in institutions.

Notably, critical race theory is generally not taught in public schools and is not specifically cited in some of these new laws. However, it has become a lynchpin in the current debate over what teachers can teach about racism, history, and inequality.

Many anti-critical race theory legislators contend that teaching students about systemic racism is akin to blaming white students for harmful history. To that, psychologist Maryam Jernigan-Noesi says, “There are many things that children learn about history that do not lead to them blaming peers for historical facts.”

Jernigan-Noesi also points out that “race is a lived reality.” This is, in part, because as Jernigan-Noesi explains, young people and their life experiences are inevitably impacted by how others perceive them racially, as well as their own sense of self.

As a result, she says, “If we teach children and students to acknowledge society's use of racial categorization as one aspect of their identity, and work to help them appreciate that individuals differ with regard to race, it helps to promote positive social interactions.”

Despite this, for many educators returning to schools this fall, classroom discussion will be governed by controversial provisions in a proliferation of so-called anti-CRT legislation.

In Texas, the “act relating to the social studies curriculum in public schools,” (H.B. 3979) was signed into law this summer by Governor Greg Abbott. It goes into effect for Texas public schools on September 1.

H.B. 3979 outlines what the Texas legislature calls “essential knowledge and skills for the social studies curriculum.” That knowledge includes familiar historical documents including the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, and the Federalist Papers.

It also includes writings of founding fathers and “other founding persons” such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Sally Hemings, and Frederick Douglass.

Provisions in the law permit teachers to cover “civic accomplishments of marginalized populations,” e.g., women’s suffrage and equal rights, the civil rights movement, and the American labor movement.

H.B. 3979 also allows teachings about the history of white supremacy. It mentions writings and speeches by Martin Luther King Jr., and the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education.

Though the law permits these classic materials, it prohibits teachers from being “compelled to discuss a particular current event or widely debated and currently controversial issue of public policy or social affairs.”

The law states that teachers who choose to cover a current controversial issue must “strive to explore the topic from diverse and contending perspectives without giving deference to one perspective.”

H.B. 3979 bars students from receiving credit, extra credit, a grade, or course credit for participating in what it describes as political or public policy activism. This includes student advocacy through lobbying, internships, or practicums.

Notably, the law forbids “training, orientation, or therapy that presents any form of race or sex stereotyping or blame on the basis of race or sex.” Although the meaning of this is unclear, the provision seems to refer to racial sensitivity and diversity trainings for public school employees.

With respect to slavery, H.B. 3979 bars any mention in Texas public schools of the advent of slavery being tied to the founding of the country. It also does not allow teaching or “understanding of” the New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project, which reframes the founding of America around the year the first enslaved Africans reached America.

Similar new history curriculum laws in four other states follow along the lines of H.B. 3979. For example, in Idaho, H377 is titled, “a law relating to dignity and nondiscrimination in public education.” It was signed by Governor Brad Little on May 1.

It prohibits “teachers from indoctrinating students into belief systems that claim that members of any race, sex, religion, ethnicity, or national origin are inferior or superior to other groups.”

Unlike the Texas law, Idaho’s law specifically mentions critical race theory. No school district, public college or university, or public school in Idaho can “affirm, adopt, or adhere to any tenet of critical race theory.”

Likewise, in Iowa, Governor Kim Reynolds signed House File 802, to combat what she has described as “discriminatory indoctrination” in schools regarding race, diversity, equality, and racism.

The law is directed at “racism or sexism trainings and diversity and inclusion efforts” by Iowa agencies, school districts, and public colleges and universities. It specifically disallows “race and sex stereotyping and scapegoating” and went into effect July 1.

In Tennessee, House Bill 580 “establishes parameters for teaching of certain concepts related to race and sex.” It was signed by Governor Bill Lee and went into effect July 1 for Tennessee public schools.

Under the new law, teachers cannot teach students that “an individual, by virtue of the individual’s race or sex, is inherently privileged, racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or subconsciously.”

House Bill 580 does permit “impartial discussion of controversial aspects of history,” although it remains unclear what will be deemed to be impartial.

Oklahoma’s bill, HB 1775, signed by Governor Kevin Stitt in May, became effective July 1. It similarly prohibits Oklahoma public schools from teaching certain concepts associated with diversity and gender trainings, race, sex, and racism.

At least 15 other states have proposed or are considering similar legislation and if those bills are enacted, they—like these existing laws--will have to be implemented by individual school boards and school districts in the respective states.

What remains to be seen is how these broad legal prescriptions will be interpreted at the classroom level. Will teachers who discuss controversial current events face termination or other formal reprimand? Will schools that teach the 1619 Project lose funding? Who will know or decide whether a particular classroom discussion was impartial or deferential to one group of students or another?

In a statement responding to the proliferation of these laws, National Education Association (NEA) president Becky Pringle said that “hyper-partisan” politicians are trying to limit what teachers teach about “our full history and shared stories of confronting injustice.”

Pringle also described the legislative push against critical race theory as “manufactured outrage designed…to divide communities along racial lines for political purposes.”

NEA has pledged to support rights of educators to teach history, social studies, and civics in ways that expand students' knowledge and analytical skills.

“Educators…know how to best design age-appropriate lessons for students,” Pringle said.

History repeating?

Richard Delgado, John J. Sparkman chair of law at the University of Alabama Law School, agrees that political partisanship is driving these new history curriculum laws.

“I think the right wing is looking for an issue and a bogeyman,” says Delgado, who has been a critical race theory scholar for decades.

“Early in my career, I was teaching about race and civil rights and…feeling that the field was falling behind the times,” Delgado says. Eventually, Delgado discovered a community of scholars who were working on the foundations of critical race theory. “And the rest, as they say, was history.”

Giving some context to current events, Delgado points to a situation from 11 years ago, involving a Mexican American Studies (MAS) program that had been offered in Tucson Unified School District beginning in 1998. The program taught Arizona students about Mexican American history, art, and literature.

Delgado says that in the MAS program, aspects of critical race theory “seemed to have been inspiring and helpful.” Nevertheless, the state of Arizona passed a law in 2010 banning the program.

At that time, H.B. 2281 prohibited courses in Arizona public schools that “promoted either overthrow of the United States government or resentment toward a race or class of people.” It also banned courses that “were designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group or that advocated ethnic solidary.”

The MAS program was intended to improve student achievement for Mexican American students who were experiencing school dropout rates as high as 50 percent. Later, as Delgado notes in an article he authored on the subject, “Precious Knowledge,” data showed that the program boosted graduation rates by nearly 40 percent.

Eventually, following a seven-year court battle, a federal court struck down H.B. 2281 as unconstitutional. The judge held that the law was not enacted and enforced for a legitimate educational purpose.

Rather, the court said, H.B. 2281 was enacted “for an invidious discriminatory racial purpose, and a politically partisan purpose.”

Positive identity

Regarding curricula that highlight cultural achievement, Jernigan-Noesi notes that “positive racial identity development for youth—especially youth of color—has been associated with future academic success.”

“Positive racial identity has also been associated with the ability to buffer the psychological consequences of negative experiences,” Jernigan-Noesi says. This is a “critical aspect of social and emotional development for all youth.”

Because of this, she says, “teaching children about the history and reality of racism is critical in our ability to learn lessons from our past, so as not to continue such patterns.”

Kelley R. Taylor is a writer, journalist, and lawyer.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!