Climate of Uncertainty: When Teachers Grapple with Climate Science

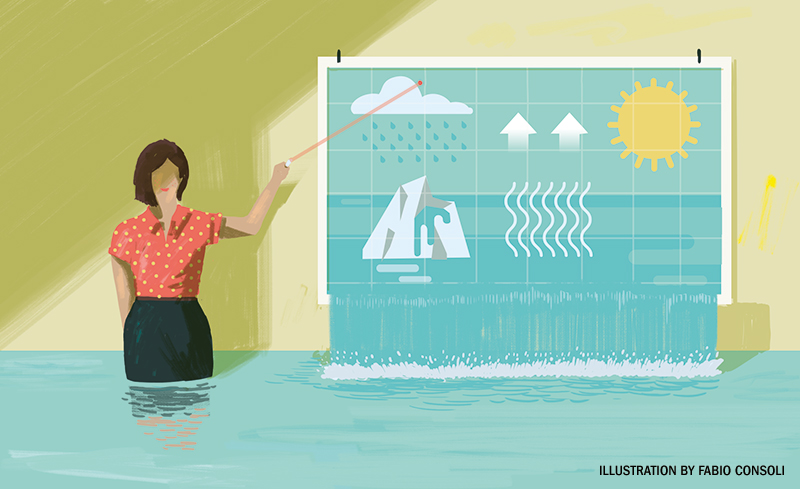

Many students are living the reality of climate change but not learning about it. Resources for educators can shape effective lessons.

Related Articles:Matter of Facts: Teaching Climate Change A Science Teacher’s Go-To Resources Collaborate with Science Teachers To Share Climate Resources |

A thick curtain of wildfire smoke hangs over Utah’s Wasatch Valley most mornings when Jenna Craker’s fifth graders take the bus to school. But even as her students live out the reality of climate change, any discussion about it stays out of her classroom.

Two thousand miles away in the coal-mining region of southern West Virginia, Curtis Stacy is midway through his 43rd year of teaching high school science. He says his impoverished students face far more immediate challenges than climate change. Besides, he’s not personally convinced humans are to blame. “Show me the proof,” he says, “and keep away from the politics.”

For many educators, teaching the human role in influencing climate is a topic rife with obstacles that simply don’t appear when they’re talking to students about other areas of settled science such as the periodic table of elements or the basics of photosynthesis. More than 25 percent of science teachers, in fact, feel compelled to give “equal time” to perspectives that doubt the scientific consensus on climate change—also called “teaching the controversy”—according to a 2015 survey.

So many non-science perspectives on climate have been slipping into science classes that in September 2018, the National Science Teacher Association (NSTA) took the unprecedented step of issuing an official statement on the topic. Authored by educators, the statement advises teachers on how to teach the evidence of human-induced climate change while avoiding the discord. Supplemented with myriad resources for teaching climate at every level, from kindergarten through high school, the NSTA document is tailor-made for teachers like Craker and Stacy, who say they need more information on how to handle such a politically fraught topic in their classrooms.

“I’m not there yet”

There is reason to doubt, however, that the message is getting through. Of the 10 science teachers interviewed for this story, none had heard of the NSTA initiative.

Take Sheila Willis, a high school AP biology teacher in Columbia, KY. Willis is a member of the Kentucky Science Teacher Association who has been teaching for 28 years. She didn’t know about NSTA’s climate science resources or position statement.

“Climate change is on my radar. I’m not there yet,” says Willis, who this year will take over the environmental science class and plans to teach climate for the first time. She plans to “pull aside from the politics of it all” and rely on the numbers. Willis is amassing data and preparing for the new content. But she says that finding and accessing reliable, current data is challenging. In other words, she’s exactly the kind of teacher the NSTA hopes to reach—but hasn’t, at least not yet.

Association leaders say they know communication is a problem. “Let me say, I am not surprised, and I’m disappointed both at the same time,” says David Evans, executive director of NSTA. Even as the largest U.S. organization for science teachers, Evans says only about one-third of the country’s science teachers are on the NSTA’s mailing list. The organization is updating its website to be more user-friendly and publishing a book on teaching climate science this month. But “absent the front page on the national press, it’s hard to get national attention and teachers are overwhelmingly busy,” Evans says.

Part of the problem is that climate science is handled very differently in various states’ mandatory curriculum standards. In New York, climate-human interaction is a state-mandated part of curriculum. Max Chomet, a ninth grade science teacher in the Bronx, says there’s no question about whether he will teach climate science. It’s required knowledge for the state assessment.

|

Students are living the reality of climate change but not always learning about it.Photo by Dutchy/Getty Images |

Let the data do the talking

In Utah, on the other hand, climate science is not on the yearly exam. Craker would have to find time and resources to teach the additional content on top of the four other subjects and required science curriculum she already teaches.

Craker acknowledges a need for better training. She is now teaching in her third state in four years—each job in a politically conservative area. She’s all too familiar with the dissension and stress that talking about climate change can provoke in her young students.

“It’s no small thing to suggest to a 10- or 11-year-old child that what they’ve heard from their parents is wrong,” says Craker. She’s not quite equipped to wade into those waters.

Even West Virginia’s Stacy, a self-proclaimed denier of human influence on climate, endorses NSTA’s emphasis on data and evidence to teach climate change. “I think that has to be the best way to go about it,” he says.

Stacy wants to see the resources himself. “There’s enough scientific proof? I’d like to see that proof,” he says. “If, in fact, if it’s there—and I don’t think it is—I’d like to see it. If it’s going to be taught, I need those.”

Upon hearing Stacy’s request, NSTA’s Evans said, “That definitely gives me hope. That’s exactly what I hope teachers would say. I’d be happy to show him the evidence, to help him find the evidence.”

The key in the classroom is to let the data do the talking, Evans says. Relying on the numbers protects the teacher from taking a side; instead they can be a provider and explainer of information. “The anchor of science is that our understanding grows with what we measure—the evidence,” he says. “It’s in distinction to being opinion-based or authority-based.”

Students Fighting Climate ChangeThe growing number of international student educational and activist groups include: Alliance for Climate Education Campaign Against Climate Change Schools Strike 4 Climate, staging a March 15, 2019 action |

But leading with the numbers has a broader application when it comes to teaching climate science. It’s a pivotal opportunity to teach a generation how to discern fact from opinion, and how to build arguments based on evidence.

“I think it’s really helpful [for students] to know that whatever statements I’m making, I should have some evidence to back it up. That goes beyond science to other topics and all of their life,” says Cree Magill, a science teacher in Fort Worth, TX.

Even when you have the data, it doesn’t always resonate. Jim Sutter is an environmental geologist turned high school biology and environmental science teacher. Though he’s been teaching climate science for only four years, he’s found it essential to personalize the message and the data. Hurricanes and wildfires don’t resonate with his Wellston, OH, students, and many of the students in this former coal-mining town recoil at the word “environmentalists.”

Sutter uses local scenarios and local data to engage students. He has them collect their own water samples so they can see that the familiar orange tint to local streams is actually caused by iron runoff. Sutter makes it clear how water contamination affects fish and wildlife species that are important to his students.

“I’m flexible about topics. We focus on ones where we can see the issues happening,” he says. Most important, he lets them take the sample, read the data, and draw the conclusion. Climate science has to resonate with the students before Sutter feels he can scale it to a global level.

Without clear examples that her students can relate to, Holly Reiser says she would face apathy in teaching climate science.

“There’s not ownership or accountability if it doesn’t apply to them. Even the most devastating event isn’t personal,” says Reiser, an AP biology and chemistry teacher in Chelsea, MI.

But even careful teachers like Reiser and Sutter run into controversy. Sutter, who was featured in a 2017 New York Times article, has been called a polarizing individual and even accused of brainwashing by some parents in his community. In a school with a developed environmental science program, Reiser must face opinionated students—and their parents—who don’t believe in climate change.

Still, educators persist—asking for evidence, pointing to local examples, and looking for ways to help students connect. Making it personal motivates students to think more critically, says Reiser. Students are more likely to develop their own ideas and less likely to be concerned with what others think when they make a personal connection with an issue. Critical thinking, not the detailed minutia of climate science, is the long game.

It’s about “giving students power and knowledge,” Reiser says. “Because they have information, examples, and connections, now they are able to make a claim and argue for it”—a skill as valuable to our society as it is to our environment.

Donavyn Coffey is a New York City-based science journalist.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!