A California High School Trains Young Adults for Jobs and Life

Civicorps Academy in Oakland, CA, is filling a void as educators increasingly focus on preparing students for postsecondary education or careers. Eighty-three percent of the program’s graduates are in college or working a year after graduation.

At a recent health summit at Civicorps about healthy lifestyles, students cycled through stations focusing on cooking, positive sexuality, martial arts, making beats, and more. Photo by Avery Moore.

During her freshman year, Roxanna Elias decided she wasn’t suited for a traditional high school experience. School seemed chaotic at two different California high schools she attended before trying to earn her diploma through a GED program in Richmond, CA. She felt isolated and didn’t think anyone else shared her struggles. But as soon as she enrolled in Civicorps Academy, a unique high school attached to a job training program in Oakland, CA, she realized that school didn’t have to be a lonely, frustrating experience. “I saw a big change and I saw the progression really fast,” says 19-year-old Elias. “I can actually become somebody.” Civicorps is filling a void at a time when educators are increasingly focused on preparing students for postsecondary education or a career. The program is meeting the needs of Oakland-area students who, for a variety of reasons, left high school, but are not content pursuing a GED program. Civicorps was founded in 1983 as a conservation corps, meaning it is part of a state agency that offers young people work in environmental conservation, fire protection, land maintenance, and responding to natural disasters. In 1995, Civicorps was granted a charter from the Oakland Unified School District to become a diploma program. The program is also part of AmeriCorps, a program supported by the federal government and the private sector in which people commit to full- and part-time positions that benefit their communities.

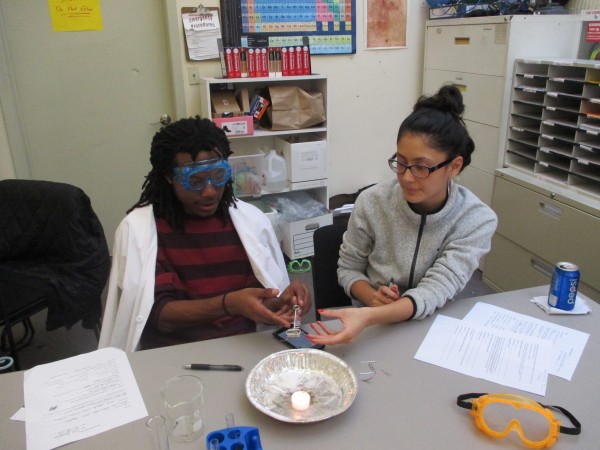

A Civicorps chemistry class. Photo by Caitlin Cruz.

“Once you feel like you have people who have your back, then it’s okay to get involved in the uncomfortable process of learning,” says English and social studies teacher Erica Lorraine Scheidt, who joined the school this year. She is also the author of the young adult novel Uses for Boys (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2013), which has served as another way for her to connect with students. Students age 18–26 attend Civicorps for 12 weeks, five days a week. They are not there just to recover credits but to complete assignments, research papers, and portfolio work linked to real-world situations and topics that interest them. As they advance through the program, they are assigned to the job training center where they work on crews assigned to public agencies such as the East Bay Regional Parks District, Alameda County Flood Control, and Caltrans, the California Department of Transportation. The students earn $12.25 per hour, work 32 hours a week, and continue the education portion of their program in the evening. Even if the students have no interest in doing environmental or other public sector work in the future, the jobs give them practical experience they can put on a resume. The school also trains them to apply and interview for jobs, and they learn the importance of showing up on time and being dependable employees. Jiovany Torrijos Hernandez, 19, returned to Oakland about a year ago after living in Mexico, where he was helping his grandmother. He became interested in the program after hearing about it from a friend. Expecting to graduate in December, Hernandez has been working on research project about childhood obesity. He is planning to go to community college and ultimately would like to attend the University of California, Santa Cruz and study physical therapy. “The people actually care about you,” he says, contrasting it to the large public high school he used to attend. “You can tell your teachers are trying to help you. They want you to better yourself.”Providing wraparound support

Martial arts at the health summit. Photo by Avery Moore.

Civicorps serves about 130 students, including some who already have their diplomas but are part of the job training program. To enroll in the academy, students, who must be be 18 or older, fill out a simple application and provide a birth certificate, immunization records, and a transcript from their most recent high school. To be part of the job training program, they have to prove they are authorized to work in the United States. If they aren’t, alternative work is designed for them, says head of school Paul Paradis. The school has four teachers as well as other instructional specialists. Most of the students who enroll at Civicorps have faced significant challenges during their school-age years. Almost all of them live in poverty, and at least 40 percent have learning disabilities; about the same percentage have been convicted of a crime. Many have children of their own, and several have been in the foster care system or have been homeless. They left high school, and sometimes middle school, for a variety of reasons, such as having to work, take care of a child, or just because they fell too far behind or lost interest. Typical alternative or adult schools and GED programs also didn’t work for these students, primarily because they were trying to complete the work without teacher support or while battling the other problems in their lives. “If you have already failed at something and someone hands you a [GED] packet, how would you feel?” asks Michele Moore, Civicorps’s director of development and community engagement. “You need the love and support we provide. They know we’re behind them.”

Chemistry class. Photo by Caitlin Cruz.

Because Civicorps students face multiple obstacles, a wide range of supportive services are built into the program. There are case counselors, college and career counselors, and instructional assistants alongside teachers in the classroom. Collectively, they provide a “high-touch” experience, Paradis says—meaning that the school provides strong support and a low teacher-student ratio. While immersed in this environment, “That’s when they figure out that they’re smart and they have a lot to offer,” Moore says, adding that instead of the academy being a second chance for these students to earn a diploma, for many, “it’s their first chance.” The students move through the program with a cohort and develop relationships that provide support. “We have a morning circle so we can reflect on everything,” Elias says, referring to a daily session before classes start in which students practice mindfulness and discuss any issues or successes among the student body. Once a week, there is also a community meeting involving staff and students that might include a guest speaker or a reading. Students also have meals at school and even have access to food they can take home. Assistance with housing or transportation issues is provided—whatever is standing in the students’ way of completing the program. Scheidt understands that mainstream high schools don’t meet the needs of every student. She was one of those who needed to take a different route. Earning her GED at 15, she later earned an undergraduate degree in writing and poetics from Naropa University; a master’s in creative writing from the University of California, Davis; worked in public relations and marketing; and volunteered as a creative writing teacher before completing her teaching credential. Because of her own negative experiences with high school, she was excited to have the chance to be part of a school where students are “connecting to the material through their own experiences,” she says. Eliminating obstacles for Civicorps students also involves working in partnership with other programs that focus on youth at transitional points in their lives. The organization Beyond Emancipation works with youth in Alameda County who are aging out of the foster care system and beginning to live independently. Men of Valor Academy, which helps formerly incarcerated men earn job skills and employment, also refers some of its clients to Civicorps.

A discussion during the health summit. Photo by Avery Moore.

Because the school doesn’t have a library, Civicorps is also working in partnership with the Oakland Public Library, where librarian Amy Sonnie, who leads the Adult Literacy and Lifelong Learning department, is building a list of resources to help Civicorps students with their school projects. The library is also getting all students library cards and can provide additional tutoring through its Second Start Adult Literacy program. Sonnie plans to visit Civicorps to demonstrate online resources such as Learning Express Library, which offers both academic support and career information, and Gale Cengage Learning, the publisher and educational content provider for libraries. Working with Civicorps, Sonnie says, illustrates that young people do not always fit into traditional categories. “Many libraries separate services into children, teen, and adult. Transition-age youth can get lost in that picture,” Sonnie says. “These students have unique needs when it comes to schooling, work, financial independence, and family.”Preparing for college and career

The school also focuses on students’ goals beyond earning a high school diploma. They spend time learning about financial aid for college, how to prepare resumes, professional emails, and cover letters, and how to dress appropriately for a job. Volunteers from local businesses also conduct mock job interviews to help students rehearse for the real thing. “It’s not just high school; it’s a lot of life skills,” says Patricia Alvarado, 25, who started at the school in August and wants to go to college and work in the medical field. Civicorps tracks its students after they leave, and the data show that 83 percent of graduates are in college or working a year after graduation. Because Civicorps is part of AmeriCorps, students can also earn scholarship money for college. Once students are in job training or part of an apprenticeship program, the academic component of the program doesn’t end. Hernandez works for Caltrans, spending his days along the highway, pulling weeds, cutting trees, and sometimes planting trees. In the evening, he returns to the classroom to complete more assignments in his portfolio. “I feel positive to be able to go home, to feel a sense of pride,” he says. “Hey, I went to work today, I went to school. I did what I had to do.”RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!