Beyond Reading Levels: Choosing Nonfiction for Developing Readers

It’s crucial that librarians engage with teachers in conversations around text complexity and reading levels.

Also read:

"Thinking Outside the Bin: Why labeling books by reading level disempowers young readers"

Reading Level Systems

Three proprietary systems dominate the education and publishing fields today:- Lexile

- Accelerated Reader (A.R.)

- Fountas & Pinnell Guided Reading

Factors that influence nonfiction text complexity

There’s no doubt that the amount of nonfiction available for young audiences is massive. What should librarians and teachers look for when selecting material for developing readers? Because the overarching purpose of nonfiction is to inform, begin by looking at the content. Does an author offer interesting, correct facts in an engaging manner? What other factors should be considered? Print size and design: The design of information books clearly impacts how accessible it is for developing readers. Consider whether the type size and line spacing is appropriate for the intended audience. Paragraph length also influences the information-load for readers. Think about whether the content is accessible in manageable chunks, or whether it might be overwhelming for developing readers. Headings help readers preview information and organize it in their minds. Do these headings and subheads use consistent type styles to draw attention and keep organization clear? Moreover, think about whether the headings are explicit enough for readers' needs or if they just pique interest. Visual text features: Other visual elements such as illustrations, diagrams, captions, and time lines help convey important information in nonfiction texts. These text features are not always in the main body of the text, but they can provide essential support for developing readers. As K.T. Horning writes in From Cover to Cover: Evaluating and Reviewing Children’s Books (HarperCollins, 2010), “It is important not to lose sight of the main purpose of illustrations in a book of information: to provide information by complementing, supporting, or extending the text.” This is especially true for developing readers; text features must be explicitly aligned to the main idea. Illustrations alone do not provide enough support for burgeoning readers; captions and labels in diagrams focus attention. These can capture essential information, show relationships, and provide a scaffold for readers as they summarize information. To see the effect that text features have on a text’s complexity, let’s look at Volcanoes by Martha E.H. Rustad (Capstone, 2014). A diagram clearly shows a volcanic eruption (see p. 6–7 in Google Books preview). Instead of just using text to describe the process, a diagram highlights key vocabulary, shows different parts of the volcano, and illustrates the movement of lava. Pair this with Elizabeth Rusch’s Volcano Rising (Charlesbridge, 2013) as a read-aloud in the library, which will draw students’ interest and encourage them to explore the topic in more detail. Vocabulary & word choice: Nonfiction books, by their very nature, contain many words that will be new to young readers. As with any specialized topic, awareness of key terms and vocabulary is critical to understanding nonfiction material, particularly for those who may have limited vocabularies. Since it is not possible to provide students with enough background knowledge to account for all specialized terms, it is critical for easier books to have specialized words defined clearly right on the page. As books get more challenging, they include glossaries and assume readers have a stronger subject-specific knowledge. When you provide students with a variety of books, they build important skills to identify words they do not know or understand. As you gather together books across a range of reading levels, think carefully about the vocabulary demands. Professional reviews often indicate whether nonfiction titles have glossaries, but only by looking closely at the book itself can you see what reading level this supports. Writing style & text structure: As you delve into the text, notice the writing style to see how clearly the author organizes the information. Expository text may be written in a question/answer format, or it may pose a problem and then investigates the solution. As Melissa Stewart thoughtfully discusses in her blog “Celebrate Science,” nonfiction authors often blend several styles. Even if they do this, however, young readers need to be able to see the structure so they can organize the information in their own minds.Building Text Sets: the ladder of complexity

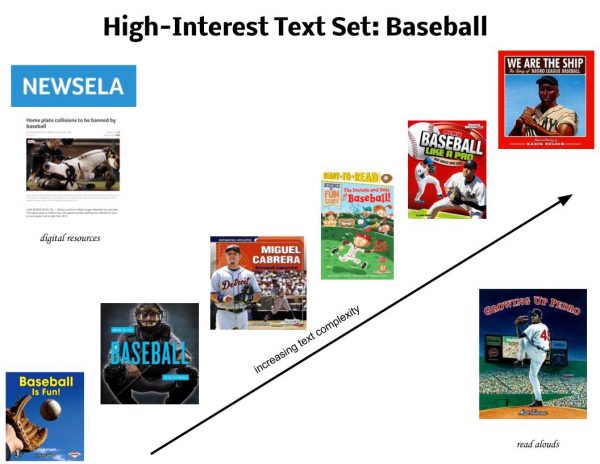

A primary goal in the school library is to help students read increasingly complex texts about subjects they want to learn more about. Choice and access are undoubtedly key in achieving this goal. We must provide access to texts across a range of complexity so children can get plenty of experience reading just-right, high-interest texts. In order to study how nonfiction texts become more complex, the best thing to do is to assemble a selection that progress up the ladder of complexity and compare them. How do they change? What differences do you notice? Here is a text set we developed for baseball. School library collections must have materials that provide entry points for a wide range of readers. We cannot expect readers to jump from a text for beginning readers to a biography of a modern ball player right to Kadir Nelson’s iconic We Are the Ship (Jump at the Sun/Hyperion, 2008). It is essential to complement books that students can read independently with nonfiction read-alouds, such as the powerful picture book biography Growing Up Pedro by Matt Tavares (Candlewick, 2015), and online digital resources, such as articles from NewsELA. Engage your students in this activity as you analyze your existing collection. Ask them to compare books they’re reading on a subject and organize them in a ladder of growing complexity. Then talk about what features make books harder to read. Is it just the word length and sentence length, or are they noticing more? It is not just important to have a set of books to meet different reading levels, but also to provide a variety of texts for children to share and explore together.

It is essential to complement books that students can read independently with nonfiction read-alouds, such as the powerful picture book biography Growing Up Pedro by Matt Tavares (Candlewick, 2015), and online digital resources, such as articles from NewsELA. Engage your students in this activity as you analyze your existing collection. Ask them to compare books they’re reading on a subject and organize them in a ladder of growing complexity. Then talk about what features make books harder to read. Is it just the word length and sentence length, or are they noticing more? It is not just important to have a set of books to meet different reading levels, but also to provide a variety of texts for children to share and explore together. encouraging curiosity, building conversations

Curiosity plays a critical role in drawing children to nonfiction. As children begin to see the connection between having a question and discovering the answers between the pages of a book, the difference between reading fiction and nonfiction becomes evident. With nonfiction, a reader may pick up a book on a topic of interest, glance through it, and find that they need more information about a different aspect of the topic in order to answer their question. Encouraging children to explore a book is important. Providing them with tips to navigate nonfiction, such as the table of contents, headings, endnotes, and resources, allows them to identify exactly what they are looking for and learn how to seek it out in additional titles. Unlike fiction, nonfiction often allows readers to jump around the text and examine a small portion before moving onto the next chapter. Rebecca L. Johnson’s When Lunch Fights Back: Wickedly Clever Animal Defenses (Millbrook, 2014) can make readers curious about the hagfish. They might stop to explore another text about hagfish, as well as a video, before returning to the book. Ask yourself: are you encouraging your students to be curious, avid nonfiction readers? As children get excited about a topic, they want to talk about it. It may begin simply with two students exploring the images or photographs in a book and talking about what they are seeing, and evolve into looking at labels and other text features to gain understanding. These organic conversations provide a way to deepen their reading. Kids will return to a nonfiction book over and over again as new questions arise or as they decide to delve into another aspect of a topic. Reading nonfiction collaboratively encourages children to spend more time with a book than they might have done on an individual level. In order to support curiosity and collaborative reading of nonfiction, it is critical to make high-quality nonfiction available and visible to kids. A display of books ranging from easier to harder reading levels around a specific topic or a variety of high-interest subjects will attract children and often become a gathering place for them to discuss what they are reading. As children discover something interesting or even gross, they just need to share this discovery and call over a friend or two. Each student adds to the conversation by asking questions or sharing what they know about the topic. Though this style of reading looks very different from when a child engages in a novel, it is valuable for children to become proficient, enthusiastic readers of increasingly complex nonfiction.Mary Ann Scheuer is an elementary teacher librarian for the Berkeley (CA) Unified School District and founder of the blog Great Kid Books. Alyson Beecher is a Literacy Coach for the Pasadena (CA) Unified School District and founder of the blog Kid Lit Frenzy.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Dyslexia Inspired

Hello, I am writing from the Facebook called #Dyslexia Inspired. We are a global community of people with dyslexia and dysgraphia. I am interested to know how libraries select decodable books for struggling readers. We know that parents turn to the librarian for help when a child has dyslexia. We look forward to hearing from you. These are the children who feel " low self esteem" when comparing their " leveled books" to their peers and they know they are in the " low reading group". Many are fortunate to get some type of OG help depending on the country they live in. Thank you kindly .Posted : Sep 02, 2017 08:48

Elizabeth Rusch

Thanks for a fascinating article. Another way to think about how to encourage students to love reading nonfiction is to create displays where books are grouped by author. Kids who love a novel will often try another by the same author. This is easy to do in libraries because an author's fictional work is grouped by last name. But what if a child loves a particular nonfiction book? Most of the time he or she can't just look on the shelf next to the new favorite book. If a nonfiction author writes on a variety of topics, his or her books will literally be spread throughout the library. This is true of my books, which cover music, history, geology, space exploration, engineering, the environment, and activism. But I would guess that if a young reader likes one of my books, he or she may like other books I have written. Each writer has a unique approach, sensibility, use of language and storytelling. Helping readers make the connection between books by the same nonfiction author could encourage readers to delve into topics that they didn't even know they liked. Thanks, librarians for all do you to get the right books into the hands of young readers! This article revealed for me how complicated that can be...Posted : Aug 30, 2017 01:39

Vicki Cobb

Great information. Readers might also want to know about a free resource on the web: www.nonfictionminute.org-- a daily posting of short essays (edited by veteran publisher/editor, Jean Reynolds) on myriad topics written by the award-wining children's nonfiction authors of www.inkthinktank.org. Each Minute is accompanied by an audio file of the author reading his/her Minute so that the content is accessible to less fluent readers. Since we first published in 2014, we have had more than 2 million page views and 250,000 visitors, many of which are classrooms. It is our intention to introduce children to many voices of nonfiction on subjects they didn't know they didn't know so that they can look for more by both author and topic in the library. A series of print anthologies of these Minutes are on the way. The first book of biographies will be published on Oct 10 called 30 People Who Changed the World. The publication of the Nonfiction Minute for the 2017-2018 school year resumes on September 11.Posted : Aug 29, 2017 08:03

Roxie Munro

Love this article! Nonfiction is so important - librarians often tell me that children come into the library wanting to know how things are made, or the story of a great person's life, or how something works - they don't ask for fairy tales or even fiction (at least not in elementary school). A great resource for lively, engaging, and beautifully written nonfiction is the Nonfiction Minute, short pithy 400-word pieces (with audio read by the author and visuals), free every school day of the year on great variety of nonfiction topics. http://www.nonfictionminute.org/Posted : Aug 29, 2017 07:56

Myra Zarnowski

Thank you for such an informative and sensible article. As you have shown, helping kids select nonfiction is so much more than matching kids and reading levels. It involves nurturing curiosity, a purpose for reading in the first place.Posted : Aug 29, 2017 03:09