Award-Winning Arts Education for Kids of All Abilities

Inspired by Patricia Polacco’s The Keeping Quilt, Creative Readers participants make a quilt. Each square represents part of their life story. All photos courtesy of Elise May

Creative Readers, an arts education program co-sponsored by the Port Washington (NY) Public Library (PWPL), was already a huge hit with students and parents before winning the 2017 National Arts and Humanities Youth Program (NAHYP) Award in November. The award reaffirmed what the community already knew—that the five-year initiative has been remarkably effective in engaging and teaching young people of all abilities. Creative Readers was the brainchild of Elise May, a longtime teaching artist who had developed many programs and workshops for the Port Washington school district and library. May was asked by the local Special Education PTA (SEPTA) to create a workshop that would include children who couldn’t attend schools in the district because of their disabilities.

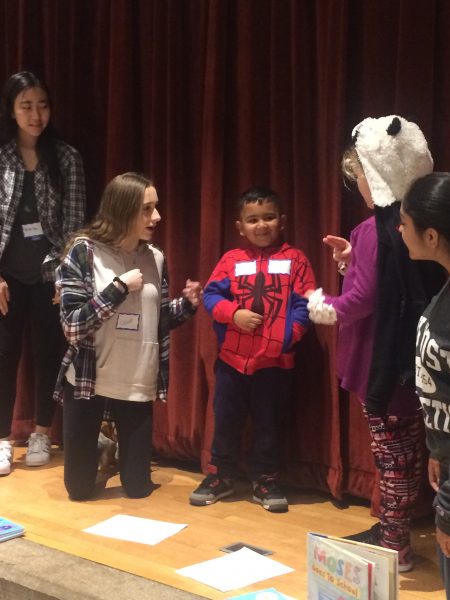

Kids learn some sign language to act out a scene from Moses Goes to School by Isaac Millman.

She realized that PWPL was the ideal location for the Creative Readers initiative, which launched in 2012. The library had already demonstrated its dedication to inclusion, the community, and the arts, says May, and it was an atmosphere that leveled the playing field for all students. The program is open to all kids—those without disabilities as well as students with a broad spectrum of physical, emotional, or intellectual challenges that prevent them from verbalizing, say, or handling strong feelings. The kids also come from a variety of classrooms, whether general education, inclusion, or self-contained. “Our goal is to engage kids and create an interest, desire, and love of books,” says May, who created the curriculum. Each weekly session focuses on a unifying theme that incorporates an opening discussion, a warm-up book that can be acted out, and an activity book. “Some book enactments are literal, while others expand on the storyline to include creative expressions through movement, music, art, or drama,” May notes. For example, when the theme is imagination, the warm-up book might be What Shall We Play? by Sue Heap, with David Shannon’s Alice the Fairy as an activity book. After the warm-up exercise, the kids create props to help them act out the story. “The library welcomed the pilot program with open arms, giving us its largest, most in-demand space,” says May. “Normally quiet Saturday mornings at the library became filled with grade-school kids, family members, program staff, and teen volunteers.” Since the program started, PWPL has included primary funding for the program in its budget, she adds. Creative Readers now meets every Saturday morning, in six-week blocks, from October to April. There are two one-hour sections, one for kindergarten through second graders and one for third through fifth graders. SEPTA handles registration and chooses each 12-student section with an eye toward creating an inclusion experience where students can interact with peers whose challenges they may not have seen before, May explains.

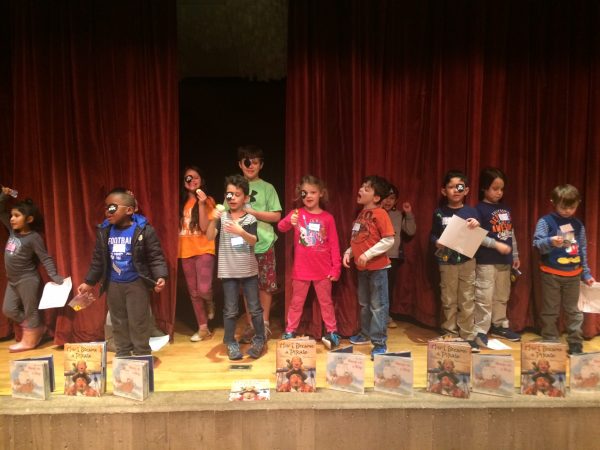

Participants talked like pirates, learned mapping skills, and followed directions to find treasure while acting out Melinda Long and David Shannon’s How I Became a Pirate.

While the focus is on books and creative expression, participants also develop skills such as empathy, cooperation, and problem solving, May says. They are also making eye contact, naming their feelings, and gaining confidence. Perhaps most importantly, they socialize—with one another and their teen buddies, 12 high school volunteers paired up one-on-one with each child.

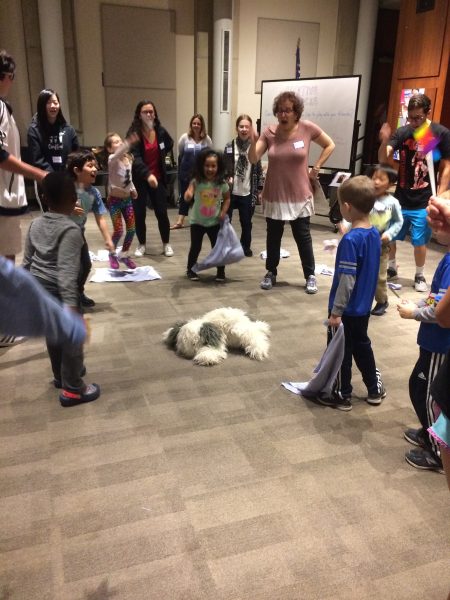

After reading David Shannon's Alice the Fairy, kids made magic wands and acted out the story, including attempting to get a dog to float. They didn't succeed, but had fun trying.

The buddies are trained to redirect focus or to control a behavior if the need arises (a behaviorist is also in the room if an adult has to step in). Teens are instructed to act alongside their young partners without squelching the child’s creativity and to provide plenty of positive reinforcement. The kids become attached to their teen buddies, May notes—and vice versa. “On Saturday mornings, these kids are not defined by what they can’t do, but rather by their strengths,” says one high school volunteer. “Creative Readers gives them a platform to break away from their so-called ‘disability’ and express who they truly are.” “Parents who may have hesitated bringing their children to the library before [now] know that it is a place for them,” adds PWPL director Nancy Curtin, who would like to share the program with other public libraries. “Their children are embraced here. They can express themselves freely. There’s no judgment, just fun.”RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!