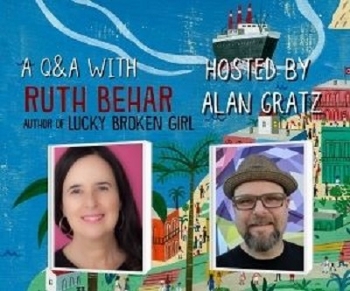

Alan Gratz, author of Refugee, Interviews Ruth Behar, author of Letters from Cuba!

My book is about a Jewish-Polish girl named Esther—the eldest in her family—who begs her father to let her be the first of the children to go to Cuba and help him get the rest of the family to the island as conditions are worsening for the Jews on the eve of WWII.

Alan Gratz, author of Refugee, raved about Ruth Behar’s Letters from Cuba saying it “will reaffirm your faith in humanity.” The two authors sat down to talk about Ruth’s book, Cuba, writing, and more. Enter to win a copy at the bottom of the Q&A!

Alan Gratz: Tell us about Letters from Cuba.

Ruth Behar: My book is about a Jewish-Polish girl named Esther—the eldest in her family—who begs her father to let her be the first of the children to go to Cuba and help him get the rest of the family to the island as conditions are worsening for the Jews on the eve of WWII.  Esther flees poverty, rising anti-Semitism, and growing uncertainty, promising to keep a record of her journey in letters to her younger sister, Malka. Seasick as she travels alone to Cuba, she questions whether she has made the right decision. Upon arriving in Cuba, she discovers that her father is a peddler and barely earning any money. Rather than taking her to live in elegant Havana, he brings her to a sugar-growing town, Agramonte, in the countryside of Matanzas, where no Jews live at all. Though Esther quickly settles in and finds friends among Spanish-Cuban, Afro-Cuban, and Chinese-Cuban neighbors, she worries about her family who are desperately waiting for their steamship tickets. She realizes she is going to have to take matters into her own hands, literally. Tossing away her woolen dress that is too hot and itchy for the tropical climate, she sews a light and airy dress for herself, using the thimble her mother gave her as a parting gift. That’s when she has a revelation—sewing dresses might just be how she’ll reunite the family in Cuba.

Esther flees poverty, rising anti-Semitism, and growing uncertainty, promising to keep a record of her journey in letters to her younger sister, Malka. Seasick as she travels alone to Cuba, she questions whether she has made the right decision. Upon arriving in Cuba, she discovers that her father is a peddler and barely earning any money. Rather than taking her to live in elegant Havana, he brings her to a sugar-growing town, Agramonte, in the countryside of Matanzas, where no Jews live at all. Though Esther quickly settles in and finds friends among Spanish-Cuban, Afro-Cuban, and Chinese-Cuban neighbors, she worries about her family who are desperately waiting for their steamship tickets. She realizes she is going to have to take matters into her own hands, literally. Tossing away her woolen dress that is too hot and itchy for the tropical climate, she sews a light and airy dress for herself, using the thimble her mother gave her as a parting gift. That’s when she has a revelation—sewing dresses might just be how she’ll reunite the family in Cuba.

AG: In fact, despite famous true stories like the tragedy of the St. Louis being turned away from Cuba, many European Jews like Esther and her family did find refuge in Cuba before and during the war. Why do you think that side of things isn't as well known?

RB: It hurts to think about the tragedy of the St. Louis in 1939—a ship filled with over 900 German Jewish refugees which was not allowed to disembark in Havana and whose passengers were sent back to Europe to face the Nazis. This cruel rejection is often the only thing people know about the history of the Jews in Cuba. That’s unfortunate, but it’s understandable. The event was traumatic and dramatic. The story was covered in the news and became the subject of the famous film, The Voyage of the Damned, starring Faye Dunaway. As a result, less attention has been given to the stories of more than 15,000 Jews from Eastern and Southern Europe who settled in Cuba in the first decades of the twentieth century and began a new life. Filled with hope, these Jewish immigrants founded Ashkenazi and Sephardic communities, schools, synagogues, and even cemeteries, because they expected to remain on the island for many generations. Since I was part of that community that found refuge in Cuba, I didn’t learn about the tragedy of the St. Louis until I was an adult. Growing up as a Cuban Jew in the United States, what I heard from my family was that the Jews of Cuba called the island home. They wept bitter tears when they fled after the 1959 revolution and went into exile with broken hearts.

AG: Letters from Cuba was inspired by the story of your own grandmother Esther, who immigrated to Cuba from Poland as a young woman. Can you tell us about her and her journey? How is she similar and how is she different from the Esther in your book?

RB: My maternal grandmother, like Esther in the book, begged her father to let her be the first of the children to go to Cuba and help him bring the family to safety. He wanted to bring her younger brother; he thought a boy would be better able to work. But she convinced him that she, too, could work hard, and if he let her come first, she would not disappoint him. My grandmother told me this story many times and it made a deep impression on me. As she grew older, she’d sometimes added, sadly, that she felt her younger siblings hadn’t appreciated how hard she’d worked to save them. I knew one day I’d have to tell her story. But I wanted the freedom to create a fictional Esther, and so in the book I made her younger than she was in real life when she arrived in Cuba. I decided she’d live in Agramonte, just with her father, my great-grandfather, when in real life she lived there with her husband, my grandfather, and the entire family after they arrived from Poland. Though I made those changes, I imbued the fictional Esther with my grandmother’s immense curiosity about the world and her desire to find a home in Cuba. In that sense I felt I was being very true to who she was. I’ll always remember how she adored Cuban black beans. The doctor told her not to eat frijoles negros because they aggravated her indigestion. But she’d savor the caldito, the broth of the beans. In that way she let herself enjoy a quintessential dish that brought back memories of Cuba.

AG: You were born in Havana yourself, weren't you? Will you tell us about your life there, and when and how you came to the United States?

RB: I feel lucky to have been born in Havana. It is a gorgeous city. Soon after I was born, my parents rented a small apartment in Vedado, in the newer section of Havana, and that was where I spent the first years of my life. We were half a block from the Patronato, the Jewish Community Center, and close to a park with ancient banyan trees and a gazebo. We were near the sea, as well, a few blocks from the Malecón, the wall that protects Havana from being swept away by the floods of the hurricanes. I briefly attended a Jewish day school, and there’s a picture of me in my school uniform to prove it. My parents and my younger brother and I fled Cuba after my father was threatened at gunpoint, and we spent a year in Israel, before beginning a new life in New York in the early 1960s. I was five going on six, one of many children of that era who had an interrupted childhood, hearing the stories about Cuba, but unable to go back because of the political divisions and the embargo. I grew up between Havana and New York, an habanera and a newyorkina, speaking Spanish at home and English in school, and celebrating the Jewish New Year and Passover with our Jewish Cuban family. Bar mitzvahs and weddings were joyous with cha-cha-cha music and a conga line. On summer weekends, after trekking out to Jones Beach and returning thoroughly sunburned, we’d go eat Chinese Cuban food at the Asia Continental on Roosevelt Avenue.

RB: I feel lucky to have been born in Havana. It is a gorgeous city. Soon after I was born, my parents rented a small apartment in Vedado, in the newer section of Havana, and that was where I spent the first years of my life. We were half a block from the Patronato, the Jewish Community Center, and close to a park with ancient banyan trees and a gazebo. We were near the sea, as well, a few blocks from the Malecón, the wall that protects Havana from being swept away by the floods of the hurricanes. I briefly attended a Jewish day school, and there’s a picture of me in my school uniform to prove it. My parents and my younger brother and I fled Cuba after my father was threatened at gunpoint, and we spent a year in Israel, before beginning a new life in New York in the early 1960s. I was five going on six, one of many children of that era who had an interrupted childhood, hearing the stories about Cuba, but unable to go back because of the political divisions and the embargo. I grew up between Havana and New York, an habanera and a newyorkina, speaking Spanish at home and English in school, and celebrating the Jewish New Year and Passover with our Jewish Cuban family. Bar mitzvahs and weddings were joyous with cha-cha-cha music and a conga line. On summer weekends, after trekking out to Jones Beach and returning thoroughly sunburned, we’d go eat Chinese Cuban food at the Asia Continental on Roosevelt Avenue.

AG: You've been back to Cuba as an adult, and to Poland as well. What was your experience with both of those places as a visitor?

RB: I have been back to Cuba many times. My visits to Cuba are part of an ongoing journey to stay connected to the place where I was born. I have done anthropological research there on literature, culture, and art, as well as on the history of the Jews in Cuba. I have built a whole other persona for myself in Cuba, a kind of parallel life, publishing poems and short stories in Spanish, and being known on the island as a poet and writer. I have visited all the houses and towns and cities where my family once lived, and I’ve traveled to places they never knew in Cuba. The island is inside me now.

To Poland, I went once in 2006, six years after my grandmother’s death. I’d asked her to accompany me there many times, so we could visit Govorovo, where she was from, but she always said she had no desire to see Poland. I went with one of my former students who had written a dissertation about Poland and knew her way around. We visited Govorovo, but what was most amazing was my meeting with an 86-year-old survivor from Govorovo who lived in Warsaw. He was full of energy and remembered my family and life in the town before the war. He’d lived in many countries after the war and knew eight languages, but English wasn’t one of them. Lucky for me, it turned out he’d lived in Spain, so we spoke in Spanish! Everything came full circle. It was a blessed moment. I imagined my grandmother looking down and smiling.

AG: Was there anything interesting in your grandmother's story, or anything interesting you found in your research, that didn't find a place in the book?

RB: I was torn about the ending. I knew my grandmother’s grandmother had not made it to Cuba, that she had chosen to stay behind in Poland, not realizing the horror in store for her and other Jews. I struggled with how to tell that story. I finally decided to leave Bubbe’s fate as unknown in the novel, and discuss it instead in the Author’s Note. I also considered adding an epilogue, in the granddaughter’s voice, telling the story of her grandmother’s later migration to the United States. In the end, I decided to keep the book focused on the time period in the late 1930s.

AG: You have a doctorate in cultural anthropology from Princeton University, and you're a professor of anthropology at the University of Michigan. What is cultural anthropology, and how has it guided your other career as a writer?

RB: Cultural anthropology is the study of humanity in all of our vast cultural diversity. It began as a profession that sought to understand cultures not one’s own, but anthropologists now also study their own cultures and delve into the study of identities as both outsiders and insiders. Although it was a field born out of colonialism, there were cultural anthropologists who, from the earliest days, spoke out against racism and other forms of prejudice and bias. The Cuban anthropologist, Fernando Ortiz, is one such figure. He carried out extensive research on the Yoruba culture brought to Cuba by enslaved Africans. This culture was preserved by creating parallels with the saints of Catholicism, thereby producing the blended religion known as Santería. His research was crucial in validating an often-misunderstood religion and in raising awareness of anti-Black racism. Ortiz also spoke out against anti-Semitism in the late 1930s, and for that reason he makes a cameo appearance in Letters From Cuba. As an educator for over thirty years, I believe deeply in the importance of education. Lives are enriched and saved by stories that teach us not only about our own culture but those of others as well. Writing fiction for young readers is another way for me to participate in this educational mission. As I wrote Letters from Cuba, I thought about how a character like Esther didn’t exist in children’s books when I was a child, and how nice it will be for her to be part of our literary canon, representing a story that is part of our vast cultural diversity.

AG: Much of your writing until recently was nonfiction for adults. Why the transition to writing fiction for young readers?

RB: Actually, my nonfiction writing for adults and my fiction writing for young readers are not as different from each other as might appear. Topics that have interested me all my life, such as cultural identity, vulnerability, immigration, storytelling, and crossing borders, have migrated to my fiction. There’s a certain fluidity between the different genres and audiences I’ve tried to reach in my writing. And yet, I also have to say, I’ve always loved fiction and put fiction writers on a pedestal. It was my dream forever to write novels. But having been trained as a cultural anthropologist, who took careful fieldnotes and faithfully transcribed recorded interviews, it was scary to shift into storytelling where I could make things up. I toiled for many years on an adult novel that I finally set aside. Somehow, another story then emerged, in the voice of a ten-year-old girl, and that became Lucky Broken Girl, my first novel, based on my experience of being bedridden for a year after our arrival from Cuba. I found it liberating to speak with a child’s innocence, fierce honesty, and sense of wonder. It felt as if a door had opened and I wanted to keep walking through it, into my second life as a fiction writer for young people.

AG: What's your writing process? Are you a pantser (writing by the seat of your pants), or a plotter?

RB: I am a mix of a pantser and a plotter. I outline and plot out plans for a story and I do a lot of research and reading before I get started. When I finally sit down to seriously write, I become a pantser, letting the characters surprise me as I enter into their lives. In other words, I need a map to get started, but once I’m in the territory of the story, I throw the map away and let myself wander around until I am completely lost. I think I won’t find my way, but then I do, and I feel grateful. Watching as the words fill the page, I’m often whispering, “Thank you, thank you.” I have an altar next to my desk with pictures of my ancestors and candles and seashells. I’ll look to them and think I can hear them saying, “Have faith, Ruti.”

Thank you for your questions, Alan! I’ve really enjoyed answering them!

AG: Fantastic. Thank you, Ruth! I’m glad your personal journey took you to writing for young readers, and that we have your books to read and learn from and enjoy!

Click here to enter to win a copy of Letters from Cuba by Ruth Behar!

SPONSORED BY

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!