2018 School Spending Survey Report

Tanita Davis's Coming-of-Age Novels Hit the "Sweet Spot" Between MG and YA | Under the Covers

Tanita Davis crafts multifaceted and diverse tween characters who deal with relatable issues.

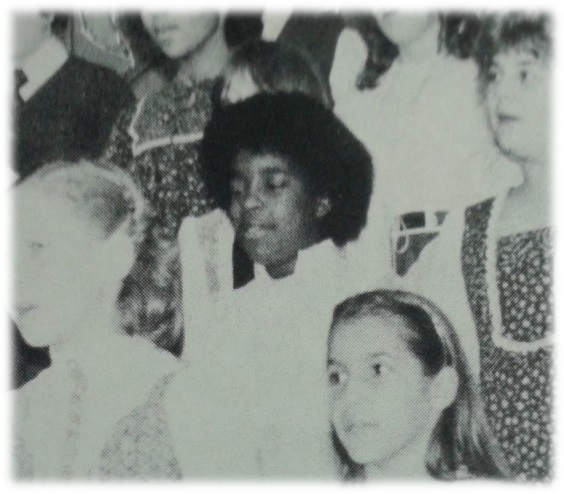

Center: Author Tanita Davis as a young tween.

Here I am, age 11, singing in the combined fifth to eighth grade choir. I was a very serious kid, wearing button-down shirts under V-necked sweaters and slacks to school. I wasn’t sporty or very coordinated but loved soccer. I had gigantic round glasses that were so heavy—and were frequently broken so I sported tape or took them off (thus my heavy-lidded squint here). I played “Chinese” (the game is German) Checkers with my classmates and read a lot of famous person biographies and religious stories, as my parents were strict about my reading. That, and Peanuts comic books, made up the bulk of my library loans. Favorite activities were reading, writing Mary Sue detective stories (Cagney & Lacey fan fiction?), singing with my friend Sharon, and nerding out as a mermaid in my friend Norma’s pool. Good times! Your books fill a much-needed spot between middle grade and young adult. You write about older characters facing serious problems, but without the content and language that is more appropriate for high school readers. Do you do this purposefully, and if so, why? It wasn’t purposeful at first…. My aim was to write books that would be considered good reading for kids who might skew younger than the cultural norm for their age, as I did, for whatever reason. Then I heard Shannon Hale speak about the gaps that she feels exist within middle grade literature, and I thought, “Huh! That’s probably where I fit.” It’s interesting to me as well, since when I was teaching, fifth through seventh graders were some of my favorite students. That’s the group still willing to speak candidly about hopes and dreams but also feeling their way through bigger themes. What do you think is the biggest difference between YA and MG? Have you considered writing a book that is strictly middle grade? I think the biggest difference between YA and MG is the extent to which the reader would consider an adult as part of the answer to any of their questions or concerns. By YA, adults are generally seen as trying to hold teens back from their desires; adults in MG books seem still willing to help kids achieve what they want. I have tried to write “straight” MG, but my one attempt has taken MUCH revision and is still on the operating table…so, we’ll see! Your book Happy Families dealt with high school students whose father is transgender. Since this book was published, the topic has gotten more mainstream media attention, and we are slowly seeing more books that address it. What prompted you to write about this topic? I didn’t at all expect to be timely—in fact, the inciting incident happened in about 2003. I was sitting in church, and the speaker was an older gentleman with Decided Views, and the jeering nastiness, the sneering curled lip with which he spoke—from the pulpit—about his brother-in-law Jack asking to now be known as Jacqueline.... It literally gave me sick chills. I wasn’t raised to get up and leave church when I disagree with something. (Frankly, I wasn’t taught to disagree—that’s a critical thinking skill many people of faith take years to learn, but that’s another story.) Consequently, I sat there, sick, teary, feeling helpless and weak. I thought, “I have to do something about this,” but I had no idea what to do. Eventually, the idea of “see something, say something” took shape in a book incorporating a faith community and person of nonconforming gender. It’s throwing a pebble in the sea, but I hope it helped more reluctant people to think…especially if they’re going to call themselves Christians. (Aaaand let me get right down off that soapbox.) My students often ask for historical fiction about African Americans that doesn’t deal with slavery or civil rights. Mare’s Ware addresses the fascinating topic of a grandmother who had been in the Women’s Army Corps during World War II. Are there any other historical topics you think would make a good story? I am learning that no matter what I think I’m “tired” of or made uncomfortable by, our whole history—including civil rights and slavery—needs to be told, just like it is within the dominant culture. However, I agree the roots of our history make a lopsided tree if those are the ONLY stories told, so…

book that is strictly middle grade? I think the biggest difference between YA and MG is the extent to which the reader would consider an adult as part of the answer to any of their questions or concerns. By YA, adults are generally seen as trying to hold teens back from their desires; adults in MG books seem still willing to help kids achieve what they want. I have tried to write “straight” MG, but my one attempt has taken MUCH revision and is still on the operating table…so, we’ll see! Your book Happy Families dealt with high school students whose father is transgender. Since this book was published, the topic has gotten more mainstream media attention, and we are slowly seeing more books that address it. What prompted you to write about this topic? I didn’t at all expect to be timely—in fact, the inciting incident happened in about 2003. I was sitting in church, and the speaker was an older gentleman with Decided Views, and the jeering nastiness, the sneering curled lip with which he spoke—from the pulpit—about his brother-in-law Jack asking to now be known as Jacqueline.... It literally gave me sick chills. I wasn’t raised to get up and leave church when I disagree with something. (Frankly, I wasn’t taught to disagree—that’s a critical thinking skill many people of faith take years to learn, but that’s another story.) Consequently, I sat there, sick, teary, feeling helpless and weak. I thought, “I have to do something about this,” but I had no idea what to do. Eventually, the idea of “see something, say something” took shape in a book incorporating a faith community and person of nonconforming gender. It’s throwing a pebble in the sea, but I hope it helped more reluctant people to think…especially if they’re going to call themselves Christians. (Aaaand let me get right down off that soapbox.) My students often ask for historical fiction about African Americans that doesn’t deal with slavery or civil rights. Mare’s Ware addresses the fascinating topic of a grandmother who had been in the Women’s Army Corps during World War II. Are there any other historical topics you think would make a good story? I am learning that no matter what I think I’m “tired” of or made uncomfortable by, our whole history—including civil rights and slavery—needs to be told, just like it is within the dominant culture. However, I agree the roots of our history make a lopsided tree if those are the ONLY stories told, so… - A nursing mystery starring a young Mary Seacole, or Nancy Drew–style sleuthery with a middle grade Jane Bolin (the first African American woman who graduated from Yale Law School).

- Imagine a Katherine Dunham dance novel or one about Nichelle Nichols, who did have a life before Star Trek.

- A book about the early NASA research mathematicians/human computers, like Melba Roy Mouton or Katherine Johnson. A story about Alton Yeats, the Air Force human speed tester for rockets, would be superb.

- Dorothy Lavinia Brown, the first black female cartoonist, or Edmonia Lewis, a Chippewa African American sculptor, would both make great books.

- A Mary Fields frontier novel would be awesome. She was an adventurous early Postal carrier. I imagine a story of Georgia Robinson, who in 1916 became the first female policewoman in L.A., or Eunice Carter, the lawyer and social worker who broke a mob-run prostitution ring in the 1920s.

- Even a story about the first African American sorority at Howard in 1908 might be worth telling.

la Carte, for example, Lainey wants to be a chef. When you were in middle school, what did you want to be “when you grew up”? Do you think that middle grade literature can offer readers dreams that might not occur to them otherwise? I wanted to be a police detective in middle school. SO badly. I blame Cagney & Lacey. And I really do think that even imagining that a career is open to A) girls or B) girls of color requires that this career is visible. In middle school, this is especially vital. Some of us don’t have realistic dreams modeled for us, so our books must do it for us first. Your books are often described as “coming of age stories.” I love the term bildungsroman! Do you purposefully set out to change your characters, or does the plot drive their changes? Purposefully…um, I wish! I am just not that slick. I don’t think I could “plan” a character shifting into the person that they need to be. I’m a seat-of-her-pantser and not a plotter, writing-wise, so the idea of outlining the character’s changes in the plot: no. A character, to me, naturally has to change, or there’s no movement in the narrative, and with no movement, there’s no purpose and no story. It seems a natural outgrowth of a character interacting with others and an expectation…but I still don’t plan it. And now I’m going to think about it every time I write! Because of the #WeNeedDiverseBooks movement, it seems we are seeing an increase in the number of books with diverse characters, but my African American students complain that the majority of books have African Americans in urban, lower-income settings. Do you have any recommendations of books that would have characters more like the ones you write? Well, prolific Brit Malorie Blackman’s books actually inspire me. She writes about kids who see ghosts, who happen to get kidnapped, who happen to get a transplant of a pig’s heart…and also happen to be brown-skinned and reading the world through that lens. A recent Elizabeth Wein offering, Black Dove, White Raven, is historical and features a suburban Ethiopian American boy who lives both in the United States and in Africa, though the book is marketed more to young adults. More middle grade–ish U.S. published suburban kid novels about African Americans include:

la Carte, for example, Lainey wants to be a chef. When you were in middle school, what did you want to be “when you grew up”? Do you think that middle grade literature can offer readers dreams that might not occur to them otherwise? I wanted to be a police detective in middle school. SO badly. I blame Cagney & Lacey. And I really do think that even imagining that a career is open to A) girls or B) girls of color requires that this career is visible. In middle school, this is especially vital. Some of us don’t have realistic dreams modeled for us, so our books must do it for us first. Your books are often described as “coming of age stories.” I love the term bildungsroman! Do you purposefully set out to change your characters, or does the plot drive their changes? Purposefully…um, I wish! I am just not that slick. I don’t think I could “plan” a character shifting into the person that they need to be. I’m a seat-of-her-pantser and not a plotter, writing-wise, so the idea of outlining the character’s changes in the plot: no. A character, to me, naturally has to change, or there’s no movement in the narrative, and with no movement, there’s no purpose and no story. It seems a natural outgrowth of a character interacting with others and an expectation…but I still don’t plan it. And now I’m going to think about it every time I write! Because of the #WeNeedDiverseBooks movement, it seems we are seeing an increase in the number of books with diverse characters, but my African American students complain that the majority of books have African Americans in urban, lower-income settings. Do you have any recommendations of books that would have characters more like the ones you write? Well, prolific Brit Malorie Blackman’s books actually inspire me. She writes about kids who see ghosts, who happen to get kidnapped, who happen to get a transplant of a pig’s heart…and also happen to be brown-skinned and reading the world through that lens. A recent Elizabeth Wein offering, Black Dove, White Raven, is historical and features a suburban Ethiopian American boy who lives both in the United States and in Africa, though the book is marketed more to young adults. More middle grade–ish U.S. published suburban kid novels about African Americans include: - "The Dork Diaries" by Rachel Renée Russell

- The Great Greene Heist by Varian Johnson

- How Lamar’s Bad Prank Won a Bubba-Sized Trophy by Crystal Allen

- The Magnificent Maya Tibbs by Crystal Allen

- The Lost Tribes by Christine Taylor-Butler

- The Perfect Place by Teresa E. Harris

- The Zero Degree Zombie Zone by Patrik Henry Bass & Jerry Craft

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!