2018 School Spending Survey Report

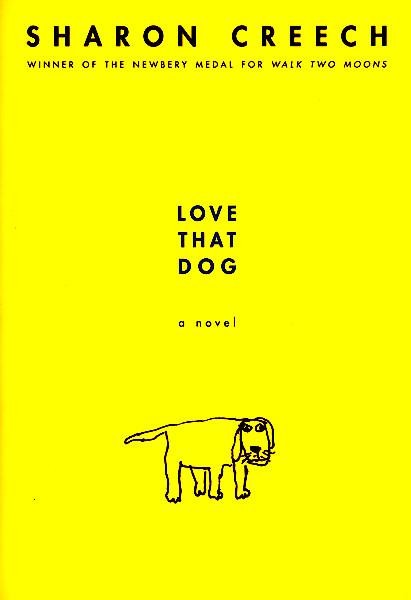

Inspiring Reluctant & Struggling Readers with Sharon Creech’s "Love That Dog" | In the Classroom

How a classroom teacher used Sharon Creech's Love That Dog to effectively engage even her most reluctant readers.

Creech’s novel in verse was a constant hit for struggling and proficient readers alike. The blue color of the letters and the use of negative space meant the words didn’t visually overwhelm dyslexic readers. Students who have difficulty processing long, complex sentences instead found themselves enjoying a fluent reading of the plot. In reading conferences, the sincerity imbued in the voice of the narrator always came up. The protagonist, Jack, struggles to understand and write poetry. Students sympathize. They feel “he’s just like me when it comes to reading.” They also laugh at his worries about being a boy writing poetry. Their reading responses contain advice on how to shed this idea that poetry is for girls. One student wrote, “Just write. Share your emotions!” The book’s length, at 86 pages, is yet another reason why it is a great fit for reluctant readers; it doesn’t intimidate them. I should note, though, that there is no loss of depth in the narrative left on the cutting room floor. Creech’s effective word choice fills the short tale to the brim with meaning. It is a model text for students learning to read not just the words on the page but what is left unspoken and between the lines. For instance, a phrase as simple as “and maybe it would look good on yellow paper” subtly communicates the protagonist’s burgeoning interest in the artistic presentation of his poems in class—a major shift from Jack’s early feelings of unease regarding poetry. The character of Ms. Stretchberry is another example of subtlety in the narrative because she is such a softly drawn portrait of a teacher. Her voice is never heard in the book; the reader can only get a sense of her from Jack’s responses to her assignments. In this way, she becomes the foundation for the conflict as a positive antagonist of sorts. First she challenges Jack by having him read and write poetry, then by telling him that his poetry is good and worth displaying in the room. Jack does not share her perspective, believing his poems are merely words in a column. This is a wonderful opener for a genre question with students. I love to ask them how they view Jack’s assessment of his own work. Most don’t share his view. They believe what he’s created is poetry because it is real and meaningfully written (about the loss of his dog). In these conversations with my students, Ms. Stretchberry reaches beyond the page to push my readers and Jack alike. She nudges us all to take risks in the classroom, ones that lead to personal growth. It is a lesson all struggling readers and the Jacks of the world need to hear: keep trying; what you’re doing is valuable even if it doesn’t always feel that way.

Creech’s novel in verse was a constant hit for struggling and proficient readers alike. The blue color of the letters and the use of negative space meant the words didn’t visually overwhelm dyslexic readers. Students who have difficulty processing long, complex sentences instead found themselves enjoying a fluent reading of the plot. In reading conferences, the sincerity imbued in the voice of the narrator always came up. The protagonist, Jack, struggles to understand and write poetry. Students sympathize. They feel “he’s just like me when it comes to reading.” They also laugh at his worries about being a boy writing poetry. Their reading responses contain advice on how to shed this idea that poetry is for girls. One student wrote, “Just write. Share your emotions!” The book’s length, at 86 pages, is yet another reason why it is a great fit for reluctant readers; it doesn’t intimidate them. I should note, though, that there is no loss of depth in the narrative left on the cutting room floor. Creech’s effective word choice fills the short tale to the brim with meaning. It is a model text for students learning to read not just the words on the page but what is left unspoken and between the lines. For instance, a phrase as simple as “and maybe it would look good on yellow paper” subtly communicates the protagonist’s burgeoning interest in the artistic presentation of his poems in class—a major shift from Jack’s early feelings of unease regarding poetry. The character of Ms. Stretchberry is another example of subtlety in the narrative because she is such a softly drawn portrait of a teacher. Her voice is never heard in the book; the reader can only get a sense of her from Jack’s responses to her assignments. In this way, she becomes the foundation for the conflict as a positive antagonist of sorts. First she challenges Jack by having him read and write poetry, then by telling him that his poetry is good and worth displaying in the room. Jack does not share her perspective, believing his poems are merely words in a column. This is a wonderful opener for a genre question with students. I love to ask them how they view Jack’s assessment of his own work. Most don’t share his view. They believe what he’s created is poetry because it is real and meaningfully written (about the loss of his dog). In these conversations with my students, Ms. Stretchberry reaches beyond the page to push my readers and Jack alike. She nudges us all to take risks in the classroom, ones that lead to personal growth. It is a lesson all struggling readers and the Jacks of the world need to hear: keep trying; what you’re doing is valuable even if it doesn’t always feel that way. RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Rosalyn Oliver-Jihnson

Please continue sharing the strategies you implement for struggling readers. They are helpful to teachers as well as parents/students.Posted : Feb 18, 2016 05:14

A Egan

"What you are doing is valuable" - words we should all live by daily. Very interesting article. You are to be commended and, YES, what you do is very valuable!Posted : Feb 17, 2016 12:24