2018 School Spending Survey Report

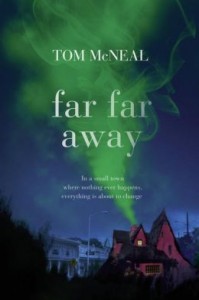

A Happily-Ever-After Ghost Story | Tom McNeal's 'Far Far Away'

Jacob Grimm, the folklorist, is dead, and stuck as a ghost. He wants to be reunited with his younger brother Wilhelm, who predeceased him. In Tom McNeal's suspenseful and haunting new novel, 'Far Far Away,' fairy tale and ghost story collide and merge.

Tom McNeal always wondered if he could handle "the complications of a ghost story." At the same time, he was also intrigued by the idea of using a fairy-tale structure. In his latest novel, Far Far Away (Random, June, 2013; Gr 6 Up) the author smoothly melds the two to create a suspenseful, haunting tale. At its center is the folklorist Jacob Grimm, stuck as a ghost. He's dead, but unable to reunite with his brother Wilhelm, who predeceased him. Jacob believes if he can help save the young Jeremy Johnson Johnson he may be able to move on. Here McNeal discusses his beguiling, macabre work. What appealed to you about the fairy tale set-up? In fairy tales, the situation changes but the characters don't. They tend to be stereotypes: the simple but kind youngest son, the girl whose true character isn't seen. What you basically have are flat characters that couldn't sustain a longer [story]. In thinking about them and reading about the Grimm brothers, the idea popped into my head: What if Jacob, the elder Grimm, became a ghost? That idea evolved…[until] the ghost story and the fairy tale collided and merged. The idea of a benevolent ghost is an interesting one, too. Jacob is almost a fairy godfather figure to Jeremy. I loved writing in the voice of Jacob. I've never written a novel in first person. Normally you have the constraints of a narrow point of view, but a ghost can observe lots of things. I found that really freeing. The story started with the characters—Jeremy and [his classmate] Ginger—and with the understanding that the ghost would intercede or try to protect them. I knew they were going to wind up in a basement, and I knew it would end happily—in accordance with the form—but I wasn’t sure how. You easily navigate the inner workings of a contemporary town, with phones and televisions, while still honoring the childhood experiences of exploring and pulling pranks in what feels like a safe place—until the children's disappearances. How did you strike that balance? As carefully as I could. I didn't want cell phones. I worried about any kind of modern technology, because I didn't want to spend a lot of the book explaining how Jacob perceives these devices. In an earlier version, there was quite a bit of that, and it was distracting. It's a fairly contemporary setting, but there are no benchmarks of time. Were you always a fan of the Brothers Grimm? You know so much about them, especially the little-known facts that come to light in the Uncommon Knowledge game featured in the book. No! I read fairy tales like everyone read fairy tales. I loved the idea of peering into your fondest hopes. You go out and do something good or generous and you win the king's daughter and live in a castle. Or looking into into your worst fears—being abandoned in the woods. Or being cut up and put in a stew by your stepmother—really, really, dark, ghoulish things—but then everything is reconstituted and made whole, and you can go about your day. The business of fairy tales is fascinating. Our attraction to them is universal. I knew very little about the Grimm brothers until I started researching them. I thought they'd written the fairy tales. I know a lot more about them now. The lifelong affinity of one brother to the other was really what was interesting to me. Most, if not all, of the Brothers Grimm tales involve someone confronting evil full on and moving through his or her fear. Was that something you wanted to work with from the beginning? Yes. I wanted Jeremy and Ginger to be tested in a severe way and to respond to the situation as their characters would, within their belief systems—that their reliance on their personal strengths would allow them to persevere, and, in the end, prevail. In an early version Jacob was the one who almost single-handedly saved them. I changed that later on—I wanted Jeremy and Ginger to participate to a greater extent in overcoming what is described in the book as evil. And through their ordeal, it's the stories Jeremy tells that sustain them. Yes. That was all new in the last version. You would have thought that would be there from day one. There's a wonderful observation that Jacob makes, "Every day, a child steps away from the parent by the littlest distance, perhaps just the width of a mouse whisker...." Yes, it's a very subtle, slow thing that happens. [As a parent,] you don't want to admit to that. You want to believe that your children need you as much as you need them. That was one of the things that was really fun about inhabiting this first-person ghost—it gave me a way to put down on paper the things I observe and think about.

Tom McNeal always wondered if he could handle "the complications of a ghost story." At the same time, he was also intrigued by the idea of using a fairy-tale structure. In his latest novel, Far Far Away (Random, June, 2013; Gr 6 Up) the author smoothly melds the two to create a suspenseful, haunting tale. At its center is the folklorist Jacob Grimm, stuck as a ghost. He's dead, but unable to reunite with his brother Wilhelm, who predeceased him. Jacob believes if he can help save the young Jeremy Johnson Johnson he may be able to move on. Here McNeal discusses his beguiling, macabre work. What appealed to you about the fairy tale set-up? In fairy tales, the situation changes but the characters don't. They tend to be stereotypes: the simple but kind youngest son, the girl whose true character isn't seen. What you basically have are flat characters that couldn't sustain a longer [story]. In thinking about them and reading about the Grimm brothers, the idea popped into my head: What if Jacob, the elder Grimm, became a ghost? That idea evolved…[until] the ghost story and the fairy tale collided and merged. The idea of a benevolent ghost is an interesting one, too. Jacob is almost a fairy godfather figure to Jeremy. I loved writing in the voice of Jacob. I've never written a novel in first person. Normally you have the constraints of a narrow point of view, but a ghost can observe lots of things. I found that really freeing. The story started with the characters—Jeremy and [his classmate] Ginger—and with the understanding that the ghost would intercede or try to protect them. I knew they were going to wind up in a basement, and I knew it would end happily—in accordance with the form—but I wasn’t sure how. You easily navigate the inner workings of a contemporary town, with phones and televisions, while still honoring the childhood experiences of exploring and pulling pranks in what feels like a safe place—until the children's disappearances. How did you strike that balance? As carefully as I could. I didn't want cell phones. I worried about any kind of modern technology, because I didn't want to spend a lot of the book explaining how Jacob perceives these devices. In an earlier version, there was quite a bit of that, and it was distracting. It's a fairly contemporary setting, but there are no benchmarks of time. Were you always a fan of the Brothers Grimm? You know so much about them, especially the little-known facts that come to light in the Uncommon Knowledge game featured in the book. No! I read fairy tales like everyone read fairy tales. I loved the idea of peering into your fondest hopes. You go out and do something good or generous and you win the king's daughter and live in a castle. Or looking into into your worst fears—being abandoned in the woods. Or being cut up and put in a stew by your stepmother—really, really, dark, ghoulish things—but then everything is reconstituted and made whole, and you can go about your day. The business of fairy tales is fascinating. Our attraction to them is universal. I knew very little about the Grimm brothers until I started researching them. I thought they'd written the fairy tales. I know a lot more about them now. The lifelong affinity of one brother to the other was really what was interesting to me. Most, if not all, of the Brothers Grimm tales involve someone confronting evil full on and moving through his or her fear. Was that something you wanted to work with from the beginning? Yes. I wanted Jeremy and Ginger to be tested in a severe way and to respond to the situation as their characters would, within their belief systems—that their reliance on their personal strengths would allow them to persevere, and, in the end, prevail. In an early version Jacob was the one who almost single-handedly saved them. I changed that later on—I wanted Jeremy and Ginger to participate to a greater extent in overcoming what is described in the book as evil. And through their ordeal, it's the stories Jeremy tells that sustain them. Yes. That was all new in the last version. You would have thought that would be there from day one. There's a wonderful observation that Jacob makes, "Every day, a child steps away from the parent by the littlest distance, perhaps just the width of a mouse whisker...." Yes, it's a very subtle, slow thing that happens. [As a parent,] you don't want to admit to that. You want to believe that your children need you as much as you need them. That was one of the things that was really fun about inhabiting this first-person ghost—it gave me a way to put down on paper the things I observe and think about.  From TeachingBooks.net, listen to Tom McNeal introduce and read from Far Far Away

From TeachingBooks.net, listen to Tom McNeal introduce and read from Far Far Away RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!