School Librarians Excel in Coding Instruction, Maker Ed, SLJ Survey Finds

School librarians are recognized as tech leaders in their schools and communities—and say their tech skills boost job security, according to SLJ's 2019 technology survey.

Download SLJ’s full Technology Survey Report |

School librarians are leading the charge to integrate tech into learning, spearheading coding initiatives, and serving as tech experts, according to SLJ’s 2019 technology survey.

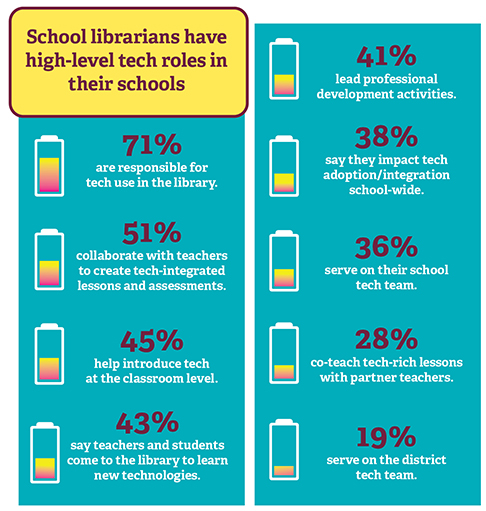

Today, 71 percent of school librarians are responsible for tech usage in the school library, survey respondents say. Additionally, 51 percent collaborate with teachers to create tech-integrated lessons and assessments, while 41 percent serve on their school or district tech team. Notably, tech skills afford 78 percent of respondents increased or somewhat increased job security.

A total of 1,008 U.S. school librarians responded to SLJ’s survey with information on how they are using robots, green screens, and virtual reality devices to enhance learning in their schools, along with details about their evolving leadership roles vis-à-vis technology.

More tech in the job title

As the school librarian job is expanding, so are the many titles used to describe what librarians do. More than half (52 percent) of respondents say their job title is “school library media specialist.” While only 16 percent are officially “teacher librarians,” most job descriptions include teaching in some capacity, either directly with students or through collaborations with teachers.

Other job titles include “21st century learning specialist,” “director of library technology,” and “director of information literacy.”

Other job titles include “21st century learning specialist,” “director of library technology,” and “director of information literacy.”

“My role is a blend of library and technology,” says Stacy Brown, who is the 21st century learning coordinator at Atlanta’s Alfred and Adele Davis Academy. “I love being able to influence the students’ learning in all areas of technology usage while cultivating a reading culture.” Brown supervises two librarians and oversees the technology spaces, including tech labs and makerspaces. Some of her projects include mentoring student technology leaders (“Network Sherpas”), a library ambassador program, an author podcast series, robotics education, and book clubs.

Most respondents (67 percent) describe their school or district tech coordinator as “supportive” or “very supportive” of their role integrating technology into the school.

The positions of certified librarian and instructional technology facilitator are frequently combined into one, often as a cost-saving measure. Many respondents enjoy the additional responsibilities, including Elizabeth Scola of Waterford Township (NJ) Schools. Scola says her job has transformed over the years as she has picked up additional duties. She currently introduces tech into classrooms, teaches STEAM classes, runs the library, administers standardized testing, analyzes the data from benchmarks to fix areas of weakness, and manages the student information system.

Scola’s district increased her pay rate to compensate for the additional responsibilities, but this isn’t the case for all respondents. In schools where the added work isn’t compensated, combined positions leave some respondents feeling like it’s a lot to manage. Erin Seretta, librarian/instructional technology coach at Papillion La Vista Community Schools in Bellevue, NE, says the dual nature of her position allows for collaboration with students and teachers. As a tech coach, Seretta incorporates the 4 Cs (communication, creativity, collaboration, and critical thinking) into classroom and library lessons.

“I appreciate the perspective this role gives me, but it is hard to do two roles justice,” she says. However, she adds, “I [am grateful for] the voice I have at the table to advocate for change and growth, which I [might] not have as a school librarian only.”

“I appreciate the perspective this role gives me, but it is hard to do two roles justice,” she says. However, she adds, “I [am grateful for] the voice I have at the table to advocate for change and growth, which I [might] not have as a school librarian only.”

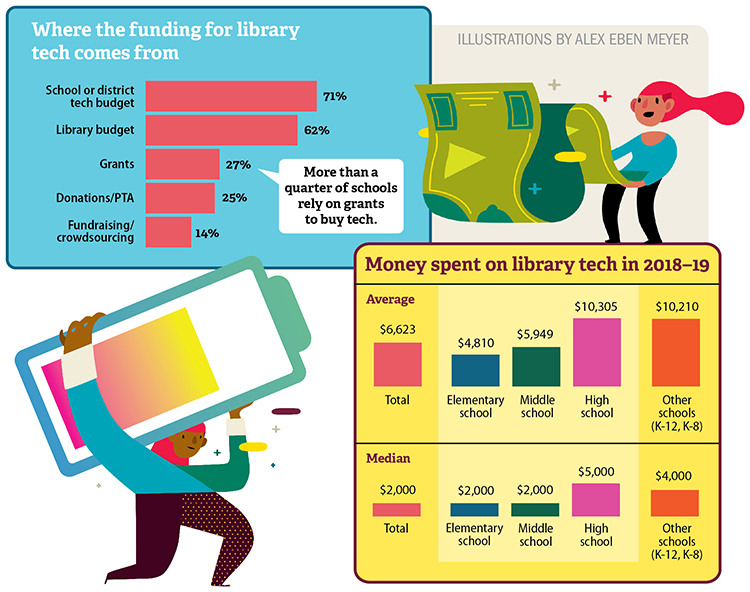

The average amount of money from all sources spent on tech for a school library was $6,623, with a median of $2,000. For those school libraries that dip into their library operating budget for technology purchases, an average of 30 percent goes toward technology. While most tech purchases are made at the district level, almost a quarter of respondents, mostly at the elementary level, bought digital subscription services, circuitry kits, or robotics.

Restrictions on websites can still significantly slow down instruction, respondents say. The sites most commonly blocked include social media, streaming services, gaming sites, and YouTube. Where those are restricted, 58 percent of librarians can unblock them. There’s good news on bandwidth, however. Now, 79 percent of school librarians report that their school has adequate bandwidth to support current Internet needs, much improved since SLJ’s 2016–17 school librarian tech survey, when that figure was 68 percent.

Maximizing creativity

Collaboration and convenience are two enormous benefits of technology. Half of the librarians surveyed say their libraries provide a dedicated space for collaborative, project-based learning. Almost 89 percent regularly use a learning management system, such as Google Classroom, for saving paper, differentiating assignments, and collaboration.

Respondents have many favorite tools; the most popular are laptops or iPads, Google Classroom, WeVideo, Flipgrid, NoodleTools, Ozobots and Spheros, Green Screen, Google tools, and Nearpod. “Both NoodleTools and Google Docs allow for the teacher or me to work alongside the student and to guide the research and writing process,” says Cathy Rettberg, head librarian at Menlo School in Atherton, CA. Free, web-based tools such as Google Earth are also popular; 93 percent of respondents have used them at least once, and 43 percent take advantage of them regularly. Open educational resources such as OER Commons are widely used, by 56 percent of respondents, and 63 percent take advantage of video chat applications such as Skype or Google Hangouts with students.

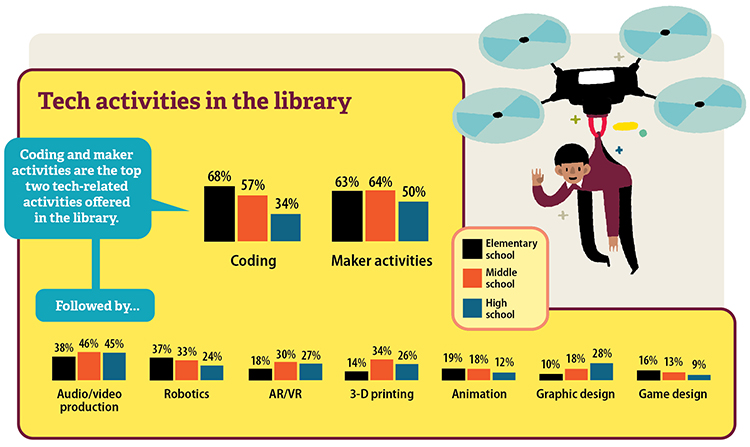

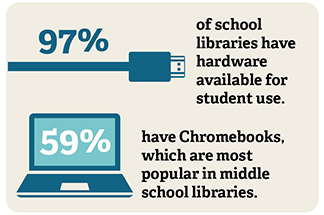

Many school librarians find that increasing numbers of students use technology to create projects for authentic audiences. For instance, Mishell Rose’s students at Bonsall West Elementary School in Oceanside, CA, print student-created books, which get cataloged and circulated. Podcast and video creation is on the rise, with 79 percent of librarians using audio hardware or software with students regularly, and 82 percent using video hardware and software with students. More than half (55 percent) of respondents interact with students using social media. Other tools available for student use and on the rise include 3-D printers, found in 18 percent of school libraries (and 29 percent of middle school libraries), and AR/VR headsets, in 16 percent of school libraries (and 23 percent of high school libraries).

Many school librarians find that increasing numbers of students use technology to create projects for authentic audiences. For instance, Mishell Rose’s students at Bonsall West Elementary School in Oceanside, CA, print student-created books, which get cataloged and circulated. Podcast and video creation is on the rise, with 79 percent of librarians using audio hardware or software with students regularly, and 82 percent using video hardware and software with students. More than half (55 percent) of respondents interact with students using social media. Other tools available for student use and on the rise include 3-D printers, found in 18 percent of school libraries (and 29 percent of middle school libraries), and AR/VR headsets, in 16 percent of school libraries (and 23 percent of high school libraries).

Michele Kirschenbaum, school library media specialist at New York City’s PS 452, is among those taking advantage of tech’s creative potential. “I enjoy using any ebook creation apps. My students love making research project ebooks. Putting the research together, typing their sentences, and adding graphics are all exciting for young kids, and it makes it easy to share their work with their parents,” she says. “I can simply share by email or embed their books on my website.”

The Ozobots Byway is a creation of Donna Knott, librarian at Thomas Dale High School in Chester, VA. Students grouped into teams are assigned a location in Virginia. The teams have to code three actions for the Ozobots to perform along a local route, which students also research for local tourism opportunities. “I am a librarian, after all,” says Knott.

Among the respondents who use these tech tools to promote library events, Lorraine LeSage of Wisconsin’s Cedarburg School District takes advantage of her green screen to make digital citizenship movies and for library promotions, such as Read Across America. Lisa Manganello of South Brunswick (NJ) High School used Adobe Spark to create videos advertising their town-wide read, which was a joint event with the school district and the public library. “My students also use it to make videos showcasing their new understandings and research,” she says.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is an area of emerging interest for librarians. The technology, found in voice assistants like Amazon’s Alexa or Apple’s Siri, allows computer systems to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence. These tasks include speech recognition, decision-making, translation, and machine learning, the intel that allows Netflix to make suggestions. The many potential uses in the classroom include speeding up administrative tasks such as grading through automation, which would potentially allow more individual time for students and teachers. Another is adaptive learning programs such as Khan Academy, which identifies levels and gaps and adjusts content accordingly.

A recent study from eSchool News predicts that the use of AI in the education industry will grow by 47.5 percent through 2021, although only about one in five librarians has a positive attitude about AI as an education tool. Nearly half of responding librarians don’t feel they know enough about AI to answer.

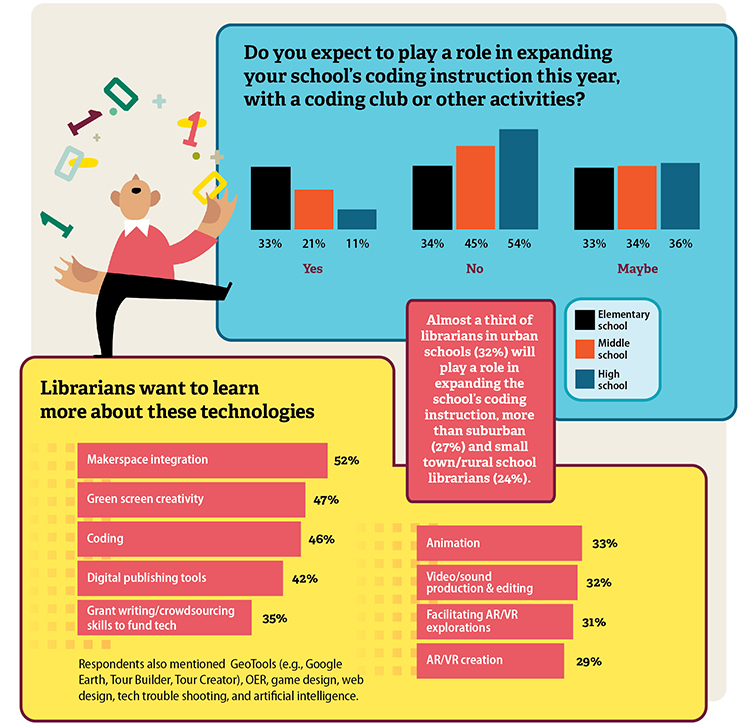

Overall, the technologies that librarians are most excited to learn more about are makerspace integration (52 percent), green screen creativity (47 percent), coding (46 percent), and digital publishing tools (42 percent). As for how they stay informed about new tools and ideas for integrating tech into the school, respondents say that they learn through colleagues and faculty (75 percent) and conference or association meetings (74 percent). Also, 68 percent use professional journals, and 68 percent turn to social media.

Coding center stage

While coding projects and maker activities don’t always occur together at schools, the skillsets used complement each other. This may explain why maker activities and coding are the two most common tech-related activities offered in the library. A whopping 65 percent of respondents use coding tools with students frequently, a significant increase from the 45 percent recorded in the 2016–17 survey. The most common tools used are code.org, Scratch, Hour of Code, Ozobots, and Spheros. Librarians who are expanding coding curricula most often work in elementary schools.

In nearly half the schools surveyed, however, coding instruction isn’t part of the school curriculum. In schools where all students are required to have coding instruction, librarians are most likely to supplement learning with coding activities, particularly in public schools. While more private schools—88 percent—include coding in the curriculum, librarians there are the least likely to offer supplemental coding opportunities.

Karen Reiber is in a small district in Ohio, at a school that offers no computer science classes until high school. As the school media/technology specialist at Wyoming Middle School, Reiber has fifth graders use code.org and then teaches them how to code Spheros.

“The real value lies in future-ready skills such as logical thinking, cause and effect, critical thinking, and problem-solving,” she says. “I believe it helps students with building character traits of perseverance, persistence, and maybe even grit. Coding empowers students to create and innovate.”

When students are not coding, Reiber offers lots of low-tech maker activities, including creating duct tape wallets and plastic window cling decorations. “I believe that these no-tech activities build those same future-ready skills,” Reiber stresses. “Sometimes the project involves reading and following technical instructions. Oftentimes students need to collaborate to complete projects, which is another skill that does not come naturally to some students.”

The most popular maker tools among respondents include circuit kits, LEGOs, and KEVA planks. “Our students use 3-D printers and sewing machines to create their own choice of projects,” says Rose. “We are pursuing a philosophy of ‘Let’s make mistakes and learn from them.’ ”

|

Methodology: SLJ emailed the school technology survey invitation to a random selection of U.S. school librarians on June 7, 2019, with a reminder on June 20. The survey link was advertised in the “Extra Helping” newsletter and via social media with a “please share” request. The survey closed on July 10 with 1,008 respondents. The data reported in total and by region has been weighted to represent the elementary, middle, and high school breakdowns in the United States. |

Jennifer Snelling writes about education technology and the transformation of learning.

Jennifer Snelling writes about education technology and the transformation of learning.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!