Politically Motivated State Superintendents Wield More Power

State superintendent has become a partisan position that increasingly impacts day-to-day decisions in school libraries.

|

Map art: Getty Images/dikobraziy (modified) |

For 50 years, the South Carolina Association of School Librarians (SCASL) worked together with the state superintendent of education and department of education, assisting in writing standards and policies. But last August, the new state superintendent, Ellen Weaver, cut ties with the organization without warning or discussion.

South Carolina isn’t the only place where state superintendents are getting more involved in and attempting to take control of the day-to-day operations and collection development decisions of school libraries. Across the country, as book challenges have amped up and attacks on certain titles and authors have become part of political campaigns, state superintendents are becoming more involved in decisions that were previously left to school librarians and district administrators. Much like school boards, the office is becoming increasingly politicized, attempting to implement partisan policy and take over district decisions.

|

|

In Oklahoma, state superintendent of public instruction Ryan Walters, who was elected in 2022, wrote a proposal to ban “pornographic” materials from school libraries and appointed Libs of TikTok creator Chaya Raichik to the state’s Library Media Advisory Committee, which is responsible for making recommendations about which books and materials should be available in school libraries. Raichik, who lives in New York and California (and is registered to vote in Florida, according to the Washington Post), is known for her anti-transgender posts. The inflammatory rhetoric of Walters and Raichik has been cited by some as a contributing factor in the death of Oklahoma nonbinary student Nex Benedict, who died by suicide a day after being assaulted in a school bathroom.

In Montana, the state superintendent of public instruction has even impacted public libraries. Last year, the state became the first to withdraw its membership in the American Library Association. The decision was made by the Montana State Library Commission, which includes superintendent of public instruction Elsie Arntzen, who supported the decision. The same commission also cut the requirement for library directors in bigger cities to have master’s degrees. Opponents of the move argued it would deprofessionalize the field.

A new phenomenon

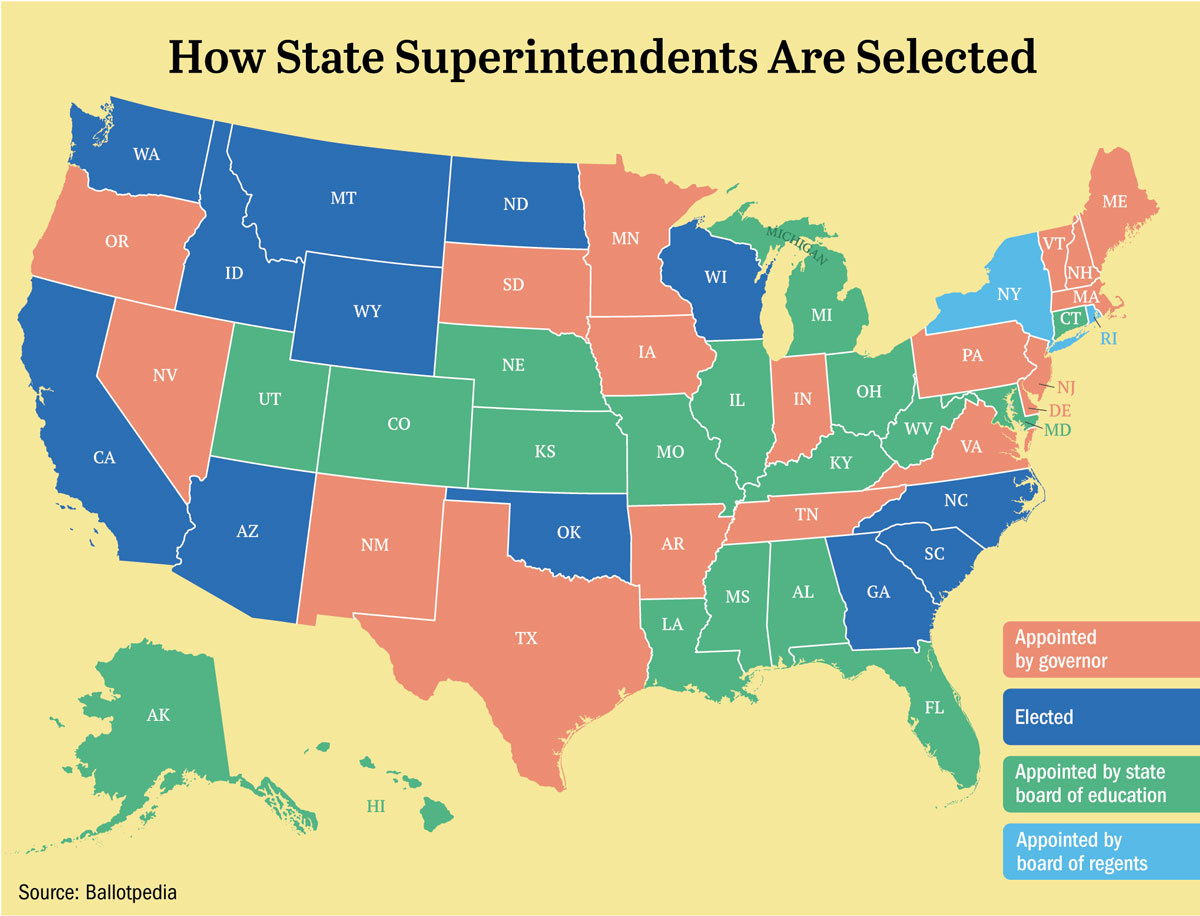

Only 12 states elect their state superintendent—also known as the superintendent of education, superintendent of public instruction, secretary of education, or chief school administrator. In the other 38, the position is appointed by the governor, the state’s board of education, or the state university’s board of regents (in the case of New York and Rhode Island). While the office is traditionally nonpartisan, eight current state superintendents have declared a party. All are Republicans.

This November, four states—Montana, North Carolina, North Dakota, and Washington—will vote on new superintendents. In North Carolina, Michele Morrow, a candidate who called public schools “socialist indoctrination centers,” won the March GOP primary and will face a former district superintendent, who is running on a Democratic ticket.

A 2023 analysis from ILO Group (bit.ly/3wFQviu), a national education strategy and policy firm, found that in states where the superintendent is appointed, candidates with political backgrounds are increasingly selected—especially Republicans.

“Our research shows that elected leaders of both parties are often using the selection of state superintendents as an opportunity to make political statements to increasingly predictable effect,” the report said.

In the past, states had no strong reasons to involve the state superintendent in issues around library collections, like establishing standards for per capita student expenditures, says John Chrastka, founder and executive director of the national library advocacy nonprofit EveryLibrary.

“Many states don’t even have that in place, let alone a directive from the state superintendent about materials that can or cannot be collected,” Chrastka says. “This is a new phenomenon, and it’s really driven by the politics of today rather than by any historic precedent or best practices around library management.”

In South Carolina, after severing the relationship with SCASL eight months into her tenure, Weaver and the Department of Education drafted legislation that would give the state—instead of local school boards—authority over school and classroom library materials. If passed, it could mean that when a book is challenged, the case could go all the way up to the state board. If the board decides to remove the book, it would be removed from all school libraries across the state. The move put SCASL and Weaver at further odds.

“Our first preference would be that we continue to put our support and trust in local school boards,” says Tamara Cox, SCASL president. “Even under great stress the last couple years, they have handled [book challenges] very well. Communities were happy with decisions that their local elected officials made. Ideally that’s what we would have liked to see remain.”

Cox became president when Michelle Spires resigned from the role, in part because of the stress of the Weaver situation and attacks from the public. The increasing involvement of the office of the state superintendent in library matters has had consequences for Cox, and other librarians, that go beyond the profession. Attacks have become personal. At a recent state board of education meeting, where Weaver’s proposed legislation was discussed, some participants in the public-comment portion accused librarians of fostering child trafficking and distributing pornography with their book selections.

“For educators who devote their lives to kids, it is so insulting to have someone say that about you,” Cox says. “The hardest part has been that these conversations have not been civil. They have not been professional. There have been personal attacks on our librarians. … It’s just emotionally painful to experience that.”

Both sides of the aisle

The ILO Group analysis suggests that state superintendents in Democrat-led states are also getting more involved in library issues, especially concerning book bans.

California state superintendent of public instruction Tony Thurmond, who was elected in 2018 on a nonpartisan platform, has been a vocal supporter of a bill that would impose consequences like fines on districts that remove any books for discriminatory reasons. It falls short of outlawing book bans broadly, but supporters say it’s a step in the right direction of protecting students’ right to read. Opponents say decisions like that should be kept local.

Betsy Snow, a librarian at Sequoia High School in Redwood City, CA, says she thinks teachers and librarians should be the central decision-makers when it comes to classroom and library materials. She supports the bill, and as a librarian she feels like Thurmond has her back.

Snow has not had any book challenges in her school library. But like Cox, she faced harassment nonetheless when her name appeared in a Fox News article claiming her library contained pornographic books.

“When I see our California leaders taking a stand, it is a sigh of relief,” Snow says. “It makes me feel like, OK, we’re going to be able to fight this and it won’t just be me fighting it alone.”

Snow hopes that California’s legislation will be a beacon of hope for other states where librarians may not have the support of their state superintendents when it comes to book challenges.

In South Carolina, Cox and her colleagues have advocated successfully for amendments to Weaver’s legislation that will make it a little easier for librarians dealing with challenges. Any complainant, for example, has a limit of only five challenges per month and one challenge per book. Also, challenges can be initiated only by a parent or guardian in the district rather than by any taxpayer. But the section about book challenges being allowed to rise up to the state level remains.

Despite the obstacles ahead, Cox remains hopeful. “We want all of our kids included and reflected in our library collections and feeling safe in all of our libraries,” she says. “So that’s what we’re going to keep working towards, no matter what regulations are given to us.”

Colleen Connolly is a Minneapolis-based journalist who writes about children and education and more. She can be found at colleenmaryconnolly.com.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!