Young Adult Friction: Chris Lynch’s ‘Angry Young Man’ examines a fragile psyche on the edge | Under Cover

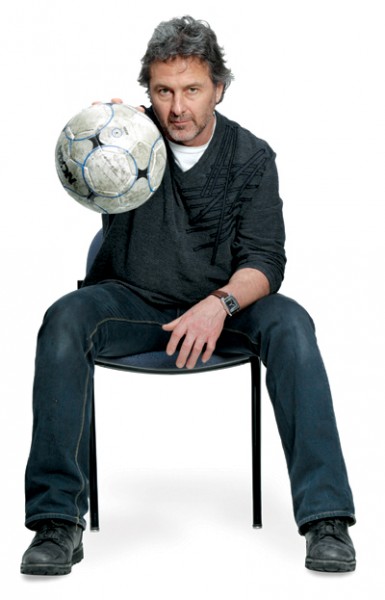

Photograph by Tsar Fedorsky/Getty Images for SLJ

In your new novel, Alexander and Robert are two teenage brothers being raised by their struggling mom. Can you give us a thumbnail sketch of them?

Sure. Alexander calls himself Xan because he likes the more exotic, outsiderish sound of it. He’s a guy like a lot of guys we know. He’s just a couple of ticks off of making his way in the world. Things just always misfire for him. I think the term outsider is wildly overused and, therefore, not very accurate. But he’s not inside of anything. He has an older brother, Robert, who pretty much makes him look worse by example, because he’s making his way and Alexander is not. And as often happens with these kind of guys, if they’re not fitting in with sports and academics and a social life, they find groups that are more interested in their particular skills—and anger is kind of a skill. So he’s a guy who winds up on the fringes of terrorism, but without any ideology at all. He’s just lost, and lost boys are dangerous boys.

I can’t stand the way Robert mistreats him—he’s such a jerk.

I think I like Robert a little better than you do. Somewhere out there my younger brother is laughing his head off.

Why’s that?

Because he’d be very pleased to have you on his side. I was really, really, really—you can put in as many extras reallys as you want to—because most of my life in the last 20 years has been an apology to my brother for the previous 30. Yeah, I was just wicked to my brother. I was an awful guy—please print that large.

You write about socioeconomic class with a sensitivity that’s seldom seen in young adult novels.

As soon as I have a subject and some characters, I kind of know where they are socioeconomically. Because I grew up without any money, I strongly relate. A lot of times, I’m generating thoughts out of my own childhood [in Boston]. I mean, my father died when I was five; my father was a bus driver. My mother was a widow with seven kids when she was in her 30s, and she was left with a car and no driver’s license. So these things very much inform my sensibilities.

Your prose is very precise and stripped down. There’s not an ounce of fat on it.

I work really consciously at leanness. I have this mode where I pull off, occasionally, the great trick of writing books that are both short and meandering, so I’m alert to that. One of the things that I teach my students is that you will write your best when you approximate as closely as possible the way you think into the way you construct books. When I look back at my life, I never see transitions, for example, I see moments. When I first encountered Joan Didion’s Play It as It Lays, I went shazam! I can do that, that’s how I think. She cuts from one thing to another to another.

How’d our photo shoot with you go?

I have a personal animosity for writer photos that say, “Look at me, look how grim and important I am.” So I really make a point of smiling all the time because I think writers should say, “Hey, I’m happy to be here.” But it was unavoidable with this particular theme and title. I know I did it to myself, but the whole time I’m going, “Oh, man. What are you doing?”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!