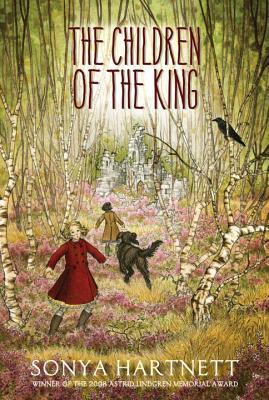

Children of the King

Children of the King, Sonya Hartmett

Candlewick, March 2014

Reviewed from ARC

Luxuriant prose, complicated and resonant themes, contemplative characters — Hartnett’s historical fiction is actually a bit of a genre-blender with thin fantasy elements woven in. Traditionally, the Printz committee rewards books that mix genres — but RealCommittee choices also tend to skew older, and Children of the King has been pegged by publisher and reviewers as a middle grade title. It’s happened before — David Almond comes immediately to mind; Hartnett’s rich descriptions and haunting strains of magic woven into the plot invite that comparison.

So when the RealCommittee sits down to discuss CotK, what will they bring up? Hartnett’s beautiful descriptions of the setting and of nature are endlessly quotable; they made me wish I was listening — or reading it aloud to someone. Her descriptions and her dialogue — of Snow Castle, of characters’ reactions, Peregrine’s compelling storytelling — are strong but instead of quoting the entire book, maybe I just need to say that I appreciated most of the characterization here. Cecily and May (and their pairing is also delicious — they come to understand each other and learn to forgive each other) in particular stand out. Jeremy’s anguish and frustration are palpable; the scene with him on the stairs was powerful. The choices he makes from then on feel totally set: irreversible.

The power of choice, the effect small choices can have on the wider world, is just one of many themes in the text. History’s effect on the present was my favorite theme; I loved the storytelling device. I loved the way Snow Castle was a physical embodiment of history in the present (here but not, part of life but otherworldly). Hartnett is skilled at using the micro to illustrate the macro. Under the themes of power, described particularly as “kingmaking,” she illustrates war time’s effects on civilians, especially children.

Peregrine is linked to Richard III — Peregrine has the power of controlling the story (and describing the king with real sympathy and understanding)…and also as a manipulator. Or is he just innocently sharing? He moves from ominous to kind to insightful to nurturing. It all culminates with him giving May the Richard III locket, and it’s hard to know what to make of all those shifts. On the one hand, kingmaking is a complicated business and there are always costs (Richard pays the price with blood, but are Peregrine’s hands any less dirtied? How many millions of people died in WW2?). On the other hand, the ending feels a little muddled by all these complications and considerations.

In fact, the ending as a whole is sudden in comparison to the tense, stately pace of the rest of the plot. Peregrine’s storytelling is dragged out over days; the two princes don’t always appear in Snow Castle even though May and Cecily seek them out regularly; Jem and his mother work through a silent and prolonged conflict before he takes any action. The tension created by this slow pace is delicious, but in the rushtotheend it has no where to go and feels wasted. The mild magic feels somewhat shoehorned in, too — she could have had similar themes and images without having Cecily and May talk to the Princes or sending them to help Jem.

I’ve been struggling the most with the question of audience here. It’s been marked for middle school (technically ages 10+), and I don’t disagree with that assessment. But when I brought it to my students yesterday and read a portion of it aloud, nearly all the students described the audience as ranging from teen to adult. Admittedly, this is a small sample size, and they only heard a tiny bit, but I still think this is food for thought. Each committee each year has to resolve the “age question” for themselves, but it’s fair to say that Printz often gives the award to “older” books. Is this a case where talking to teens would help committees through that process? Or would it be helpful to have Newbery-like wording about intended audiences and high standards (referring here to page 69 of the Newbery criteria, which is merely part of the “extended definitions and examples appendix.” I nearly passed out with jealousy at typing that sentence. SO MUCH PROCESS-Y INFORMATION TO DIGEST)?

Will all the good stuff take the day? Will the committee’s considerations about audience ultimately keep this book out of the running? Or are there enough small flaws to make all these other questions moot?

![]()

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!