Fact-Finding: Teaching News and Media Literacy Skills

In a time of deep distrust and widespread propaganda, news and media literacy skills are more vital than ever.

|

SLJ montage. Characters by Olga Kurbatova and cosmaa (both Getty Images). |

ResourcesTeaching News Literacy in the Age of AI |

The new year has barely begun, but there is one thing we know about 2026: Over the next 12 months, fake photos will be shared as real and lies repeated as truths. The information and images will move swiftly across social media platforms and into conversations in school hallways and at kitchen tables across the country. Complicating matters, technological advances will, no doubt, further hinder the ability to easily know fact from fiction.

There is perhaps nothing more important right now than knowing how to separate fact from falsehood, to spot and stop misinformation and manipulation. Adults struggle with these media and news literacy skills and kids must be taught, a job that is often the responsibility of library media specialists.

Media literacy, according to the National Association for Media Literacy Education, is the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, create, and act using all forms of communication. News literacy is the ability to determine the credibility of news and other information and recognize the standards of fact-based, high-quality journalism, according to the News Literacy Project (NLP).

Teaching news and media literacy was once about helping students confirm facts. With the introduction and proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI), the skills are as much about determining what is real as what is true. And educators must not only manage the breadth of sources of information and the advancements of technology but also pierce a growing distrust.

“What we find is this concept of deep doubt,” says NLP’s Director of Community Engagement Alee Quick. “We’ve kind of gotten to this point where we’re like, ‘Well, can we trust anything we see at all?’ Even things that are genuine, we may be skeptical or cynical and just assume that everything is completely suspect.”

Educators and students alike can’t just throw their hands up in defeat and say it’s everywhere, why bother even trying to figure out if something is real or AI-generated, fact or misinformation, Quick says.

“Media literacy, news literacy, is more important now than ever,” she says. “It is a solution. There’s hope.”

But it is an uphill battle.

Breaking through distrust

According to an NLP report, “‘Biased,’ ‘Boring’ and ‘Bad’: Unpacking perceptions of news media and journalism among U.S. teens,” released in November 2025, 45 percent of teens said that journalists do more harm to democracy than protect it.

This distrust comes at a time when “truth is under attack,” according to 2025 School Librarian of the Year Tim Jones, who added, “We are witnessing propaganda going viral.”

This year, the United States will celebrate its 250th anniversary as history is being rewritten and, in some cases, erased. Additionally, the country will hold what will undoubtedly be contentious elections for all 435 members of the House of Representatives, 35 Senate seats, and 39 governorships. Students need news and media literacy skills to navigate their world and learn how to grow up to be engaged citizens.

“Of course, there’s a connection [from media literacy] to democracy and to taking part in civic life,” says Cathy Collins, middle school librarian in Sharon, MA, and author of Teaching News Literacy in the Age of AI: A Cross-Curricular Approach, an ISTE-ASCD publication. “If you know how to evaluate quality news, then you’re going to be in a better position to take part in democracy.”

“Of course, there’s a connection [from media literacy] to democracy and to taking part in civic life,” says Cathy Collins, middle school librarian in Sharon, MA, and author of Teaching News Literacy in the Age of AI: A Cross-Curricular Approach, an ISTE-ASCD publication. “If you know how to evaluate quality news, then you’re going to be in a better position to take part in democracy.”

First, students must learn who to trust. NLP reported that nearly 70 percent said that news organizations intentionally add bias to coverage to advance a specific perspective. The words used most often to describe news media were “crazy,” “boring,” “biased,” and “fake.”

The study “should give us all reason to pause,” says Collins. “I think we’re in trouble, because when young people tune out credible journalism, they’re not just losing touch with current events, they’re at risk for losing evidence itself. When students distrust all information equally, they become easy to mislead.”

That manipulation and its impact is something Oklahoma high school librarian Molly Dettmann discusses with her students when looking at AI-generated images of real events.

“We [have] had really good discussions looking at examples where people are sharing AI images after actual disasters,” Dettmann says. She asks her students, “Why do we need AI–generated images when we have real images, we have real people dealing with these things?” and “How does that distort our sense of reality and what’s really going on in the world?”

No matter the technology, platform, source of information, or subject matter, the basics of media and news literacy instruction remain the same. It starts with knowing what makes a credible source and the editorial standards used by quality journalists. Don’t assume students know who should be considered a journalist and what that job entails when done properly. A 2024 NLP study showed that teens struggled to differentiate between news, opinion, and advertising and misidentified movie and television characters in other professions as journalists.

“They are blurring the lines between…what I refer to as the standards of good quality journalism and influencer content,” says Collins.

Once the source of the information is vetted, media literacy requires students to read laterally to confirm the information and do a reverse image search, if applicable.

|

Cathy Collins uses historical photos of nearby Boston Commons, altering one and asking her

|

It can sound like asking students to do a lot of extra work—so many steps beyond just reading what is in front of them—which might seem overwhelming, but educators are actually helping with the cognitive overload, Collins says.

“By teaching them things like lateral reading, slowing down, and asking questions, we’re giving our students what I call scaffolds that help to lighten that information overload,” says Collins.

News literacy can be worked into the curriculum of any subject, according to Dettmann, who creates lessons for English and science teachers, among others, using subject-specific examples. Dettmann likes to draw from pop culture and current viral videos to spark conversation among her students. The topic may start off seeming insignificant but digs deeper as kids ask more questions. For example, can bunnies really jump on trampolines? Is it so bad if someone creates a video where they do? Who created the algorithm that then sends one animal video after another into my feed?

Making it hands-on can help, too, Collins says. For one project, students find a historic photo; Collins then shows them how easy it is to use a tool such as Canva AI to alter it. She’ll show them a picture of nearby Boston Commons, then add some dogs, and show them both photos.

“It’s changing a slight detail and then having them guess [which is real],” Collins says. “It’s visual literacy—helping students slow down and build habits of careful observation.”

Next, she has the students create altered images and the class plays a quiz game to see if they can guess which images were changed by classmates.

“If we can tap into students’ creativity while we’re teaching, that’s ideal,” says Collins.

|

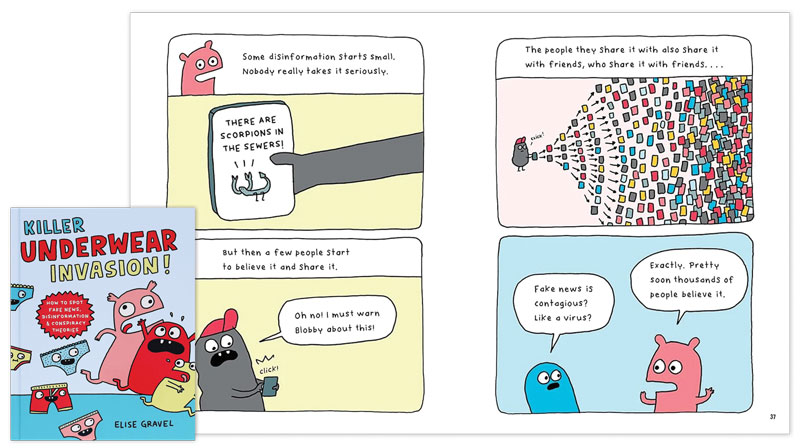

Gabrielle Casieri uses Killer Underwear Invasion by Elise Gravel to help prompt discussions about mis- and disinformation with her sixth grade students.

|

Mandating media literacy

And these are lessons students actually want. According to NLP’s study, an overwhelming majority of teens—94 percent—say that schools should be required to teach media literacy. But in most places, it’s not mandatory.

Nineteen states have taken some legislative action to elevate K–12 media literacy education, but according to a 2024 study by Media Literacy Now, at that time only eight states required that media literacy instruction be included in at least some K–12 classrooms. As few as nine have included language in their media literacy legislation that is inclusive of news literacy. Just three—Connecticut, Illinois, and New Jersey—explicitly require some news literacy instruction.

The New Jersey information literacy legislation, signed into law in 2023, was the first in the country. But those who opposed the legislation said the mandated K–12 curriculum would teach students to trust certain media sources based on their political leanings and lead to indoctrination. A conservative parents’ group said that the disinformation the bipartisan legislation sought to combat was actually just “things people don’t agree with.”

This politicization of information, media, and news literacy can make it difficult for educators, who fear complaints from parents and may face consequences from their administration.

|

Looking at news after a sporting event like the Super Bowl can show how coverage may differ depending on the location of the news organization.

|

“I have to acknowledge that is a valid concern. I do understand why people may feel uncomfortable,” says Gabrielle Casieri, president of the New Jersey Association of School Librarians, which is helping to write the state’s new information literacy standards and working with the NJ Department of Education on curriculum and implementation.

But library media specialists, she says, can do research and curate topics that won’t create controversy to use in their lessons or offer to classroom teachers. One of Casieri’s favorite ways to teach media literacy and avoid any hot-button topics is to look at coverage of sporting events. She’ll show students headlines from newspapers in the location of the winning and losing teams.

“It’s the perfect way to show bias [and] viewpoint and how these events can be viewed in two totally different ways,” says Casieri. “We have to be careful to plan so that people aren’t distracted by the content. Theoretically, as students get older and they have these information literacy skills, they can recognize that even with controversial topics they can then evaluate their sources and decide for themselves what they are going to believe.”

Casieri explores mis- and disinformation—and the motives behind them—with her sixth graders, sparking the conversation by reading aloud Killer Underwear Invasion: How To Spot Fake News, Disinformation and Conspiracy Theories by Elise Gravel.

For those willing and able to broach all subjects, media literacy can be a good way to enter important and complex conversations.

“I always look at media literacy as an opportunity to have open dialogue, to be curious about how people think about information, but also about how they think about the things that are affecting them [and] the way in which the media has had implications in their lives,” says Belinha S. De Abreu, global media literacy educator and editor of Media Literacy for Justice: Lessons for Changing the World. “It’s looking at the media as a whole and then looking at how it relates to the individual.”

For those afraid of having conversations that could turn contentious, De Abreu recommends I Never Thought of It That Way: How to Have Fearlessly Curious Conversations in Dangerously Divided Times by Mónica Guzmán. Once ready to take on that discussion, educators must educate themselves to be well-versed on the particular subject, seeking information outside their personal perspective.

For those afraid of having conversations that could turn contentious, De Abreu recommends I Never Thought of It That Way: How to Have Fearlessly Curious Conversations in Dangerously Divided Times by Mónica Guzmán. Once ready to take on that discussion, educators must educate themselves to be well-versed on the particular subject, seeking information outside their personal perspective.

“Pop the bubble and go outside of that so that you can get to more sources of information,” says De Abreu, founder of the International Media Literacy Research Symposium. “Our algorithms are limiting the way in which we’re getting things. The way in which we choose and select information is also a part of the process. It requires a lot more footwork as educators in order to step outside of those filter bubbles.”

Once informed, educators must learn what their students know, and the sources of that information.

“You need to know who your students are. You need to know what media engages them, what are they interested in right now?” says De Abreu. “They may not be interested in politics, because it’s too much, but they’re interested in things like the music industry. They’re interested in the way in which AI is playing around with deep fakes. They’re interested in pop culture. We need to go into their worlds in order to bring them into other spaces so that they can see the leveling up of how one thing relates to the other.”

Simply declaring, “This is news and this is why media literacy is important” is not helpful, she says. For all age groups, the key is to find out what media they are watching, listening to, and participating in, and create a lesson that engages them in their interests that will later connect to bigger and broader media literacy lessons.

Says De Abreu, “Understand who they are as a media consumer and then look deeper.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!