2018 School Spending Survey Report

Separating a City—and Families

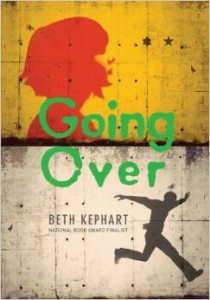

On the eve of the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, Beth Kephart's compelling YA novel 'Going Over' offers a story of the human impact of the barrier, which separated not just the city, but friends and families on either side.

Next month marks the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, perhaps the most memorable symbol of the Iron Curtain and Soviet communism. Construction of the wall began on August 13, 1961, and sealed off the border and travel between the free West Berlin and communist East. It was a means of keeping East German citizens from defecting, until fractions in the Soviet bloc and new policy decisions led to its eventual fall on November 9, 1989. Beth Kephart's compelling young adult novel Going Over (Chronicle; Apr. 2014; Gr 8 Up) offers a story of the very human impact of the Berlin Wall, which separated not just the city, but friends and families on either side. The novel takes place in 1983 and is told in the alternating perspectives of day care worker and graffiti artist Ada in the West and plumbing apprentice Stefan (“Your future is plumbing, the Stasi say.”) in the East. The teens are in love—their grandmothers were best friends as young women, and for years Ada and her grandmother have taken trips to the East to see Stefan and his grandmother—but the wall is an ever-looming barrier against future plans. There is a line between us, a wall. It is wide as a river; it has teeth. It is barbed and trenched and tripped and lit and piped and meshed and bricked—155 kilometers of wrong. Kephart’s use of first person for Ada’s narrative and second person in telling Stefan’s serves to further separate the storylines. Ada encourages Stefan to escape to the West, but Stefan, well aware of the potential pitfalls (from imprisonment to death), is far more hesitant. The West isn’t simply idealized though, and a subplot involving Turkish immigrants in Kreuzberg, where Ada lives, provides more historical context to the region. Woven into the narrative are true tales of defections—including the young border guard Conrad Schumann who leapt over the temporary barbed wired fence in 1961 and the Holzapfel family who escaped from the top of a building using a makeshift cable harness in 1965—which convey the risks real people were willing to take for a chance at life in the West. An author's note at the back further explains the Berlin Wall and escape attempts (Kephart quotes the number of deaths associated with defections at 136, though acknowledges that this figure may be higher) and successes (about 5,000), as well as the blending of fiction and fact in the novel. A list of selected sources includes both print and web resources that can be used for further study.

Next month marks the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, perhaps the most memorable symbol of the Iron Curtain and Soviet communism. Construction of the wall began on August 13, 1961, and sealed off the border and travel between the free West Berlin and communist East. It was a means of keeping East German citizens from defecting, until fractions in the Soviet bloc and new policy decisions led to its eventual fall on November 9, 1989. Beth Kephart's compelling young adult novel Going Over (Chronicle; Apr. 2014; Gr 8 Up) offers a story of the very human impact of the Berlin Wall, which separated not just the city, but friends and families on either side. The novel takes place in 1983 and is told in the alternating perspectives of day care worker and graffiti artist Ada in the West and plumbing apprentice Stefan (“Your future is plumbing, the Stasi say.”) in the East. The teens are in love—their grandmothers were best friends as young women, and for years Ada and her grandmother have taken trips to the East to see Stefan and his grandmother—but the wall is an ever-looming barrier against future plans. There is a line between us, a wall. It is wide as a river; it has teeth. It is barbed and trenched and tripped and lit and piped and meshed and bricked—155 kilometers of wrong. Kephart’s use of first person for Ada’s narrative and second person in telling Stefan’s serves to further separate the storylines. Ada encourages Stefan to escape to the West, but Stefan, well aware of the potential pitfalls (from imprisonment to death), is far more hesitant. The West isn’t simply idealized though, and a subplot involving Turkish immigrants in Kreuzberg, where Ada lives, provides more historical context to the region. Woven into the narrative are true tales of defections—including the young border guard Conrad Schumann who leapt over the temporary barbed wired fence in 1961 and the Holzapfel family who escaped from the top of a building using a makeshift cable harness in 1965—which convey the risks real people were willing to take for a chance at life in the West. An author's note at the back further explains the Berlin Wall and escape attempts (Kephart quotes the number of deaths associated with defections at 136, though acknowledges that this figure may be higher) and successes (about 5,000), as well as the blending of fiction and fact in the novel. A list of selected sources includes both print and web resources that can be used for further study. RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!