Choosing Restorative Justice: Engagement, not Punishment, Fosters Community and Respect in the Library

A common goal is to build positive connections while helping to stem negative impacts traditionally associated with wholly punitive discipline, such as school suspensions and expulsions.

|

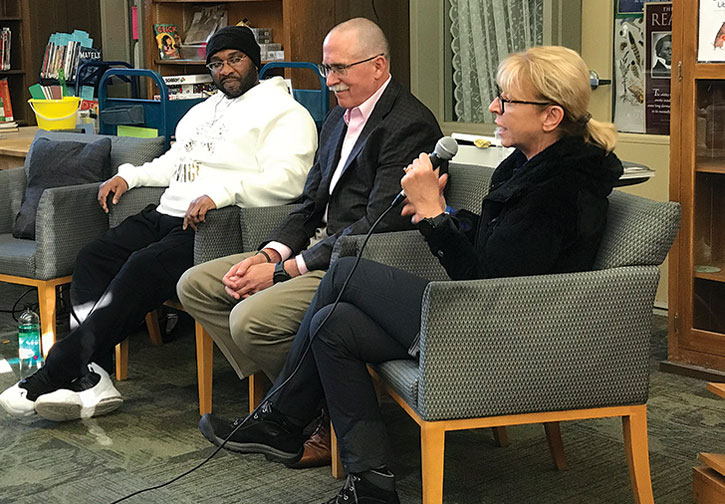

Jason Samuel (left), who served 22 years for the attempted murder of police officer Tom Morgan (center),

|

Related article:Restorative Justice: Putting Ideas into Practice in School Libraries |

Working in jails and prisons for five years and then in juvenile hall for 16 years gave Amy Cheney, director of libraries for Oakland Unified School District (OUSD), a front row seat to what she calls the bureaucracy of incarceration and punishment.

“It was disturbing to see that a basic tenet of our democracy—innocent until proven guilty—seemingly did not apply to most of the youth in juvenile hall who had not had charges against them adjudicated,” Cheney says.

That experience spurred Cheney to seek alternative ways to support young people in the criminal justice system. She wanted to help produce more positive outcomes than those associated with the trauma they had experienced and/or had inflicted on others. She began to explore restorative justice programs.

“I engaged in many trainings, the most intensive of which was Victim Offender Education through the Insight Prison Project,” says Cheney. “As a juvenile hall librarian, I brought programming, practices, and speakers focused on healing rather than punishment, to the institution.” For example, in Cheney’s Victim Offender Education program, students in juvenile hall explored their transgressions and met survivors of crimes similar to those they’d committed.

In recent years, many school districts, and public and school libraries throughout the country (including those now overseen by Cheney in OUSD), have also implemented restorative justice programs and practices. Used at all levels, from elementary school to high school, these programs are reshaping the way many districts approach school discipline. A common goal is to build and maintain strong communities while helping to stem negative impacts traditionally associated with wholly punitive discipline, such as school suspensions and expulsions. They are also seen as a way to foster more positive communication among students and staff.

Circling up

“Restorative justice refers to how we respond to incidents of misbehavior or actions that cause harm to individuals and the community,” says Christine Cray, director of student services reforms for Pittsburgh Public Schools (PPS). Because schools have different configurations and environments, restorative justice looks a little different in each building, and practices can vary depending on the age group. Cray cites one example of an elementary school shifting traditional lunch detention to a “restorative lunch.”

During these meals, students engage in conversation about various behaviors and actions. “This might include looking at what it means to be responsible and how they can show responsibility at home and at school, rather than simply sitting silently in a room to serve lunch detention,” she says.

The five-year-old restorative justice program at PPS was inspired by a strong interest from district and community leaders in being more culturally responsive and reducing racial disparities in the use of exclusionary discipline. Studies show that students of color face harsher penalties for similar school infractions than white counterparts.

“In traditional disciplinary models, students receive a consequence for misbehavior but often do not talk about what occurred or hear about who has been affected by their behavior,” Cray says. “Restorative justice focuses on who has been impacted and how, rather than what rules have been broken. Hearing that you have disappointed someone who cares about you…is hard.”

With restorative justice, the goal is not to make students feel bad. “We aim to use that shame in a positive way, to make sure that the individual understands that their actions were unacceptable, but that they are still an important member of the school community.”

Read: Books About Doing Time | Read Woke

In PPS, this might involve engaging students in conversation about their mistakes to evaluate their behaviors and actions and to create a plan to make it right. Depending on the situation, restorative justice can be used along with or in lieu of traditional punishment.

The PPS program also uses proactive strategies designed to build strong relationships and community by promoting an environment where everyone feels included and valued. One example is circles, where a class is gathered to sit so that all can see one another. An underlying theory is that ongoing opportunities for open communication and community connection build empathy and trust. Those positive connections may reduce behavioral issues and bullying.

Students respond to prompts ranging from get-to-know-you questions like “Who is your favorite superhero?” to topics aligned with academic content, such as “What do you admire about the character in this story?”

Cray says that “everyone shares and listens,” and facilitating adults participate alongside students.

To foster engagement and deeper conversation, circles can be used in different ways for different age groups. A middle school might use a check-in, check-out circle to begin and end the week with students. Circles might also be used during parent meetings to guide discussion on topics like bullying or academic dishonesty.

The circle and restorative questions “provide adults and students with safe, predictable routines and ways to talk about serious issues,” says Cray. Restorative questions focus on an incident and vary by situation but might include “What were you thinking about at the time?” and “Who has been affected by what you have done?”

Oakland Unified has pioneered this approach since it began implementing restorative justice in its schools in 2007. The district’s program also uses circles in the first tier of a three-tier system of support. “We focus on identifying shared values, providing proactive social-emotional support, and creating connections and community,” says David Yusem, restorative justice coordinator.

|

Fremont (CA) High School students bond while wrapping up a circle.Photo courtesy of Oakland Unified School District |

They often take place in the school library. “Librarians have been doing circles for years,” Yusem says. “Libraries are larger, feel-good spaces where students can have those conversations. We can mingle classes or have professional development groups in.”

Typically, a librarian or teacher will have students relate socially or emotionally to a book, character, or quote, and use the restorative process to have a conversation that helps cultivate a sense of community. This mirrors the bibliotherapy often used in trauma-informed libraries, where students may identify with a character and feel more comfortable talking about the character than themselves. Group discussion helps students develop insight to cope or respond differently in the future.

“Restorative justice can at once be about instructional practices and strengthening social-emotional learning muscles like self- and social awareness, empathy, and patience,” Yusem says. “Everyone brings a value in a culturally responsive way and we create a foundation for ongoing conversation.”

In the second tier, smaller groups deal with a specific harm or conflict, and staff try to get to the bottom of what happened using a restorative approach. For example, a student who causes harm might go into mediation or a restorative circle process with all the stakeholders—i.e., the children responsible for the harm and the those who were harmed.

In terms of restorative library policies, Cheney says that everyone in the school is responsible for the library. “If harm occurs—in the smallest of examples, a book is lost or damaged—we talk about how the book belongs to the community and discuss how to rectify the situation without punishment. Stakeholders [create] a plan to repair the harm as best as possible and follow through and follow up.”

The district’s final tier focuses on individualized support. They might welcome a student back from a difficult time or embrace an international student through a support circle. Or they may have a farewell circle for a librarian going on maternity leave and then a welcome circle for the substitute librarian. Yusem describes tier three as offering a healthy way to cultivate community, which the district considers essential to fostering the empathy and connection needed to promote positive behavior.

Yusem says that another important reason OUSD uses restorative justice and practices is to embrace civil rights and address the “overuse of suspension and expulsion.”

“Punitive discipline disproportionately affects students of color due to cultural biases that have been finely crafted over the years,” he says. “We need alternatives to exclusionary discipline to [make] school a place of equality and equal treatment.”

RESOURCESThe International Institute for Restorative Practices provides information on restorative circles and free webinars on restorative leadership Restorative justice at the Oakland Unified School District The Schott Foundation offers a toolkit and list of resources on restorative justice WeAreTeachers.com has general information about restorative justice and how it can work in the learning environment |

Reducing suspensions

Staff in Arizona’s Pima County Public Library system (PCPL) were also looking for alternatives to exclusionary discipline for youth.

“We recognized higher suspension rates among our young customers than those of our adult patrons,” says Em Lane, interim branch manager at Wheeler Taft Abbett Sr Library and founding member of the library’s Restorative Practices for Youth team. “At that time, however, suspension was our only tool.”

The library began to research how schools used restorative practices and met with the county’s community justice board. “[That] inspired us to set up restorative boards in branches that had high youth suspension rates,” Lane says.

Since its 2017 pilot program, PCPL has implemented restorative practices at 26 branches. The focus is on active listening, open-ended questions, and co-creating alternatives to suspension. The goal is to build relationships with local youth before issues arise.

“Traditionally, a young customer would receive a suspension if they violated our code of conduct,” says Lane. Now, in the immediate aftermath of a specific incident (e.g., a student breaks a chair), staff who are also trained in restorative approaches are encouraged to ask, “What happened?” and then listen to the youth explain themselves.

In Pima County libraries that have a restorative practice board—two to three trained community members and a youth worker—the youth meets with the board for 30 minutes to talk about what happened. Those meetings might involve filling out worksheets, brainstorming how to avoid repeats of the behavior, and/or discussing strategies for controlling emotion or anger. Usually, the result is an agreement between parties that involves a consequence, but one where the youth is still welcome at the library.

Read: New Book Explores Solutions for Black and Brown Girls Disproportionately Disciplined at School

“The goal is to help the young person understand the impact of their behavior on customers and library staff,” Lane says. “These are essential life skills to learn and build upon.”

An ideal space

Pima County Library has seen a reduction in youth suspensions, but the process of implementing restorative practices has had some challenges. “The main [one] has been helping staff understand that the library is changing the way they interact with youth,” Lane says.

For OUSD, long implementation times and budget constraints are ongoing hurdles. “Restorative justice takes years to implement and fully understand,” Yusem says. “It is not just about policy and procedures, but embracing a philosophy.” This requires training and opportunities for educators to practice these processes.

Cray agrees that implementing anything new in a large organization like Pittsburgh Public Schools can be challenging. But she says that as school staff and students became accustomed to using restorative practices, school interactions and relationships have grown more positive.

Lane echoes that sentiment. “[In our libraries], we have seen an increase in heartfelt conversations, jokes, and high fives, and kids feeling more comfortable to approach us with questions,” he says. “That is what happens when you focus on the whole person instead of just the ‘bad’ behavior.”

Though there is no one-size-fits-all approach to alternative discipline in schools, Cheney believes that the library is an ideal space for restorative justice to flourish. “The library provides a solid space for community and diversity of thought that is often respected and upheld by the community,” she says.

“Also,” she adds, “in part because the library is the most beautiful and comfortable space on the campus, our restorative justice program is likely to expand—if not blow—student’s minds. That is the best thing a library can do.”

Kelley R. Taylor has covered food literacy, trauma-informed librarianship, and web accessibility for SLJ.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!