Sponsored

Graphic novels have become not just a fixture in the cultural firmament but also a true force in the literary world. While genres, styles, and topics may vary wildly, one thing that publishers agree on is this: Making graphic novels available in school libraries can give children access to stories they might otherwise miss.

The librarians huddled around a table at SLJ’s annual Leadership Summit probably hadn’t played with wooden blocks since they were in grade school themselves.

Recent releases from Cherry Lake include thorough overviews of special sporting events, clear and organized guides to Fortnite, and books about different ways kids can help others at home, at school, on the playground, and around town.

Scholastic has long embraced the power of story through our simple mission to encourage the intellectual and personal growth of all children, a growth that we believe begins with literacy. We know that stories empower, stories transport us to new worlds and introduce us to new characters, but perhaps most important of all, stories have the power to connect us.

Sera Reycraft’s American journey began in a United States Department of Defense school in Korea. At age ten, her mother married her stepfather, an American government official living abroad.

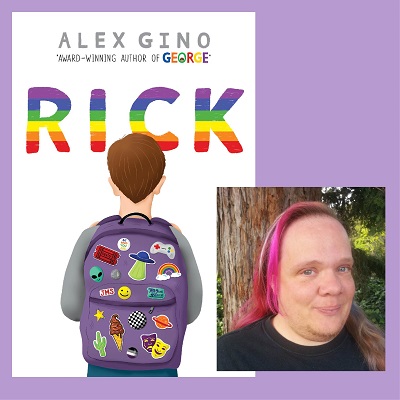

Stories are genuine. Stories can feel real, even when we don’t feel real to ourselves. Stories reflect who we are back at us and make it easier for us to know it’s true. This is especially important for those of us who aren’t cisgender, heteronormative, non-disabled white men from traditional families. That is, for most of us.

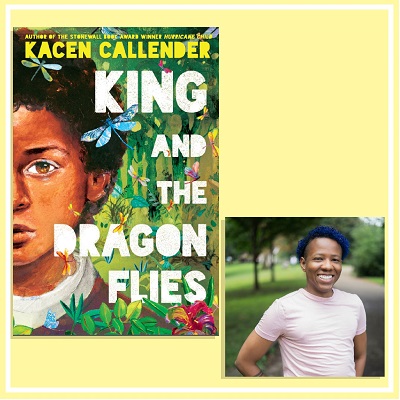

When I was young, I was bullied and isolated and felt no hope for my future. It was through reading that I felt I had friendships with the characters, that I felt someone saw me and loved me, even if none of my peers did. As an author now, I can see that someone did see me and love me—the authors of those books, who had perhaps once felt the same pain that I did.

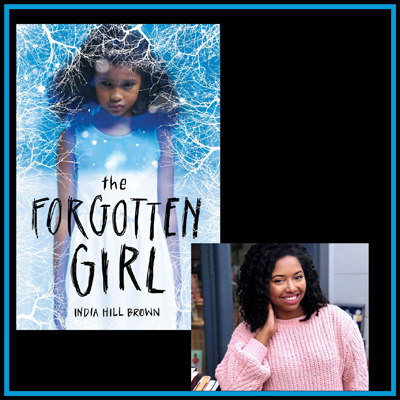

One of the reasons I wrote The Forgotten Girl was so that little girls who look like Avery and Iris and little boys who look like Daniel can see themselves on the page, and not have to spend their lives proving they are worthy of recognition from people who should realize their greatness anyway.

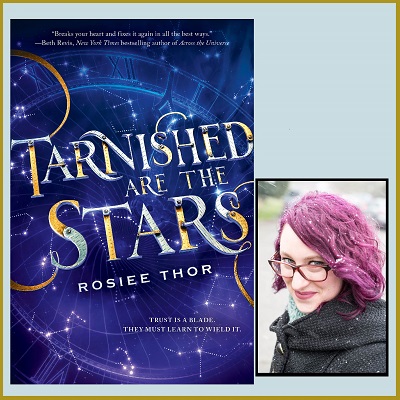

Now I know that I identify as aromantic bi-gray-asexual, and I never would have known if not for writing Tarnished Are the Stars. There’s inherent power in seeing yourself in the pages of a book, but there is power, too, in writing yourself onto those pages, in making sure your story is told.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing