2018 School Spending Survey Report

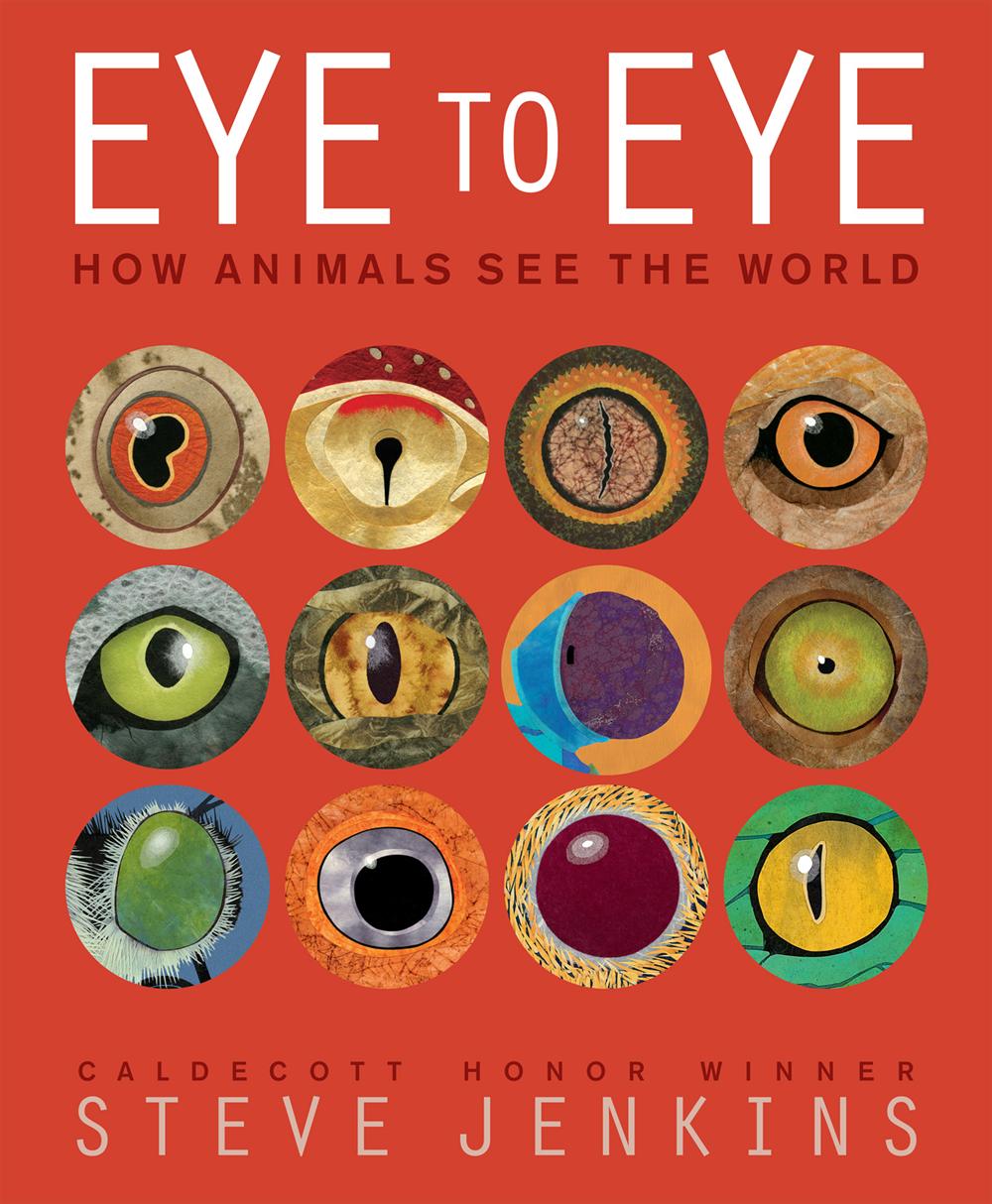

Eye to Eye: How Animals See the World

illus. by Steve Jenkins. 32p. bibliog. diag. glossary. Houghton Harcourt. Apr. 2014. Tr $17.99. ISBN 9780547959078.

COPY ISBN

Gr 3–6—The ability to perceive light and dark first developed in simple animals approximately 600 million years ago. Since that time, multiple variations of eyes have evolved from four main types: eyespot, pinhole, compound, and camera. Toward the end of the book, Jenkins devotes a page to describing the "evolution of the eye," enabling readers to easily follow the changes. Jenkins's outstanding torn- and cut-paper illustrations offer a fascinating look at these important organs, which range in size from the tiniest holes (starfish) to basketballs (colossal squid). Eyes not only allow animals to find food and avoid predators but can also assist in swallowing food and aid in attracting a mate. Large, colorful pictures of more than 20 animal eyes are accompanied by a small illustration of the entire creature and a brief paragraph of intriguing information (for example, as a halibut ages, one eye moves until both end up on the same side of its head, the panther chameleon can operate both eyes separately, and the hippopotamus has a clear membrane that enables it to see while underwater). Animal facts, a bibliography, and a glossary round out this slim volume that will captivate readers of all ages.—Maryann H. Owen, Children's Literature Specialist, Mt. Pleasant, WI

Gr 3–6—The ability to perceive light and dark first developed in simple animals approximately 600 million years ago. Since that time, multiple variations of eyes have evolved from four main types: eyespot, pinhole, compound, and camera. Toward the end of the book, Jenkins devotes a page to describing the "evolution of the eye," enabling readers to easily follow the changes. Jenkins's outstanding torn- and cut-paper illustrations offer a fascinating look at these important organs, which range in size from the tiniest holes (starfish) to basketballs (colossal squid). Eyes not only allow animals to find food and avoid predators but can also assist in swallowing food and aid in attracting a mate. Large, colorful pictures of more than 20 animal eyes are accompanied by a small illustration of the entire creature and a brief paragraph of intriguing information (for example, as a halibut ages, one eye moves until both end up on the same side of its head, the panther chameleon can operate both eyes separately, and the hippopotamus has a clear membrane that enables it to see while underwater). Animal facts, a bibliography, and a glossary round out this slim volume that will captivate readers of all ages.—Maryann H. Owen, Children's Literature Specialist, Mt. Pleasant, WIThe origins of the eye lie in the need for animals to detect light, as Jenkins explains in the opening to this excellent presentation of the structures animals use to see. After a brief description of the four major types of eyes that have evolved in animal species (eyespots, pinholes, compounds, and cameras), we get to the eyes themselves, prominently featured in well-designed layouts that serve both as study guide and display for the beautifully rendered and reproduced cut-paper artwork. Each page features a single organism in two images: a main close-up of the animal's eye area(s), carefully framed to illustrate position and function relationships; and a smaller, full-body image of the animal itself. The juxtaposition is very useful -- readers can use both images to make sense of the text, filled with fascinating information about eyes that are large (colossal squid), odd (stalk-eyed fly), all over the head (jumping spider), and extremely mobile (ghost crab). Additional field guide-like facts about the twenty-two featured animals are listed at the end of the book. danielle j. ford

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!