Something to Shout About: New research shows that more librarians means higher reading scores

Librarian Marie Slim knew the cuts were coming. She just didn’t know they’d be this bad. For nearly 10 years, there had been a certified media specialist—and a full-time paraprofessional—at each of the six high schools in her California school district.

Then things slowly began to change.

In 2009, the district got rid of four librarians, leaving Slim and another media specialist to serve the six high schools. This month, Slim will be the only librarian standing—and it’s left her with an enormous sense of guilt, not to mention dread, knowing that she’ll be completely overstretched.

“Across the state, the cuts have been crushing,” says Slim, who’ll go from serving 2,600 kids in the Fullerton Joint Union High School District to more than five times as many this fall. “It’s made me feel rotten. I have survivor’s guilt. And I know I won’t be able to make a huge dent in the reading skills of 14,000 students across the district. But I’ll keep trying, one student at a time.”

Countless media specialists around the country have had similar stories, but does anyone know how librarian cuts during this recession have hurt our students? Although it’s too soon to tell in Slim’s case, the overall news isn’t good.

For the first time, we’ve conducted a groundbreaking study using data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) to document the impact of librarian layoffs on fourth-grade reading scores between 2004 to 2009. The results are what you’d expect: in many cases, fewer librarians translated to lower performance—or a slower rise in scores—on standardized tests.

For the first time, we’ve conducted a groundbreaking study using data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) to document the impact of librarian layoffs on fourth-grade reading scores between 2004 to 2009. The results are what you’d expect: in many cases, fewer librarians translated to lower performance—or a slower rise in scores—on standardized tests.

Our research also indicates that these lower reading scores can’t be blamed on cuts to other school staff. Regardless of whether there were fewer classroom teachers schoolwide, students in states that lost librarians tended to have lower reading scores—or had a slower rise on standardized tests—than those in states that gained librarians.

The news doesn’t surprise Barbara Stripling, director of library services for New York City’s Department of Education, who says although some principals still recognize the value of highly qualified librarians in these tough economic times, many more have no qualms about getting rid of them.

Stripling says that she doesn’t yet know the extent of the damage to her district, but she suspects librarians who’ve retired won’t be replaced and others will be moved to classrooms. “Principals don’t understand what a librarian brings to the position that an aide or parent volunteer cannot,” she says. “If libraries are kept open by volunteers, then they become little more than warehouses. The negative impact on student achievement may not be immediately evident, but it will be substantial.”

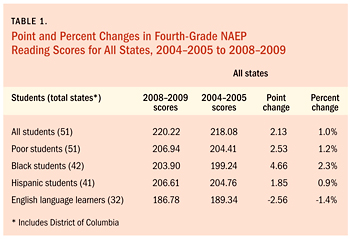

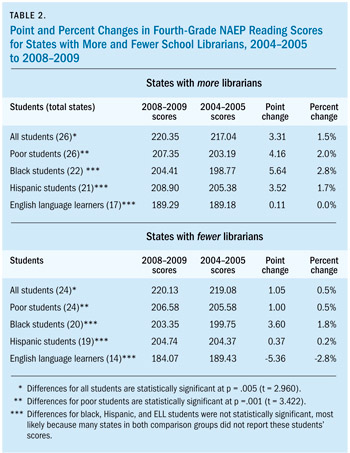

Stripling’s right. Our findings show that states that gained librarians from 2004–2005 to 2008–2009—such as New Jersey, Tennessee, and Wyoming—showed significantly greater improvements in fourth-grade reading scores than states that lost librarians, like Arizona, Massachusetts, and Michigan. Why did we examine fourth graders? They were the most widely reported scores available at the state level during 2004 to 2009 and anecdotal evidence shows that media specialists are being lost disproportionately at the elementary level.

We found that 19 of the 26 states that gained librarians saw an average 2.2 percent rise in their National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) fourth-grade reading scores. Meanwhile, 9 of the 24 states that lost librarians had a 1 percent rise. Why is this important? Because of the proportion of the difference—the increase in scores of states that gained librarians was two times that of states that lost librarians. Scores remained unchanged for 6 states that gained librarians and 12 that lost librarians. Three states that lost librarians had an average decline of -1 percent, and one state that gained librarians experienced a -0.5 percent decline in scores.

Even though these numbers may seem small, minor shifts are quite meaningful since there tends to be little overall change with fourth-grade NAEP reading scores over time. So the fact that our study shows some change in reading scores if a state gains or loses librarians is significant and worthwhile.

Minnesota’s Robbinsdale Area School District is one that’s managed to avoid layoffs—and keep a strong school library program. “I’m proud to say there are no cuts in my district,” says Sally Mays, the media specialist at the K–5 Robbinsdale Spanish Immersion School and president of the Minnesota Educational Media Organization, the state professional association. “Each of our 13 schools has a full-time media specialist—and our test scores show it.”

Every elementary school in Mays’s district has had above-average growth in math and reading from fall 2010 to spring 2011, according to the most recent results of the Measures of Academic Progress, an assessment designed to monitor student learning. Individual grade levels across all district schools—made up of kids from a wide demographic pool—also had an average increase of more than 6 percentage points in reading and 7 percentage points in math. “We have a great group of teachers who work with school librarians, some in Spanish,” Mays adds. “It makes the difference. The standards taught through a library program are aligned and correlated to classroom standards. When they are taught in authentic lessons by a certified librarian, scores are impacted and learning takes place.”

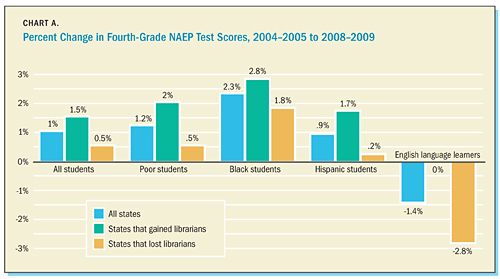

Indeed, when we compared states that gained or lost librarians to each other or to all states, those that gained librarian positions consistently fared better. States such as Alaska, Maryland, and Oklahoma, for instance, all of which gained librarians, had average reading scores for all students increase by 1.5 percent—a half a percentage point more than all states (1 percent) and almost three times more than states that lost librarians (0.5 percent).

At the same time, the average reading scores for poor students in states that gained librarians increased by 2 percent—almost twice as much as the percentage change for that group in all states (1.2 percent) and four times the percent change for states that lost librarians (0.5 percent).

That makes perfect sense to Connie Williams, a teacher-librarian at California’s Petaluma High School and a former president of the California School Library Association. “If you factor in the fact that for students in poverty the school library is most likely the only access to books, instruction, and reading advisory that they have, then yes, the school librarian can be shown to be a direct influence on student achievement,” says Williams, who also chairs the advocacy group California Campaign for Strong School Libraries.

When it came to black students, average reading scores in states that gained librarians increased by 2.8 percent—a modest boost compared to gains for that group in all states (2.3 percent), but a substantial hike over states that lost librarians (1.8 percent).

Meanwhile, the average reading scores for Hispanic students went up by 1.7 percent—almost twice the percent change for that group in all states (0.9 percent)—and, on average, a whopping eight and a half times better than states that lost librarians (0.2 percent).

English language learner (ELL) students were particularly vulnerable to the negative effects of losing school librarians. They were the only group in which averages actually decreased over time, both for states that lost librarian positions and for all states. Only in states that gained librarians did ELL scores hold their own—showing no change over time. Overall, the reading scores of ELL students in all states declined by -1.4 percent. For states that lost librarians, on average, ELL student scores dropped -2.8 percent—a loss twice as bad as the one suffered across all states.

English language learner (ELL) students were particularly vulnerable to the negative effects of losing school librarians. They were the only group in which averages actually decreased over time, both for states that lost librarian positions and for all states. Only in states that gained librarians did ELL scores hold their own—showing no change over time. Overall, the reading scores of ELL students in all states declined by -1.4 percent. For states that lost librarians, on average, ELL student scores dropped -2.8 percent—a loss twice as bad as the one suffered across all states.

Slim says she fears this trend will follow her ELL students now that’s she’s forced to serve six schools. “We have English language learners and special education students who will definitely suffer,” she explains. “Many of our teacher-librarians have spent a lot of time and energy to inspire and/or cajole those populations to read. Our most needy students will now go without. The districts say that the public libraries can fill the void, but the public libraries don’t have immediate access nor do they have the collection development priorities that we do.”

We also uncovered further evidence of the negative impact of librarian cuts on student achievement by examining the relationship between the percent change in the number of school librarians and the percent change in reading scores over time. We did this by conducting a correlation analysis, which shows whether these two factors were related, and if so, was the relationship positive or negative. Correlations can range from -1.00 (the two factors are perfectly negatively related) to 1.00 (the two factors are perfectly positively related). A 0 indicates no relationship between the two factors.

Our study showed that the percent change in the number of school librarians from 2004–2005 to 2008–2009 was significantly and positively correlated with the percent change in the reading scores for all groups except for black students (see Table 3). This means that when the percentage of school librarians increased, a percent increase was also seen in reading scores for all students, whether poor, Hispanic, or ELL. The finding that the correlation for black students was not significant is likely due to a combination of two factors: a smaller number of states reporting scores for black students and the comparatively dramatic improvements in scores of black students across the board during this period.

Our study showed that the percent change in the number of school librarians from 2004–2005 to 2008–2009 was significantly and positively correlated with the percent change in the reading scores for all groups except for black students (see Table 3). This means that when the percentage of school librarians increased, a percent increase was also seen in reading scores for all students, whether poor, Hispanic, or ELL. The finding that the correlation for black students was not significant is likely due to a combination of two factors: a smaller number of states reporting scores for black students and the comparatively dramatic improvements in scores of black students across the board during this period.

Why did we choose to examine the period between 2004 and 2009? The latest school year for which NAEP reading scores are available for most states is 2008–2009, which happens to be the one full school year during the Great Recession of 2007–2009. The 2004–2005 school year is roughly halfway between the two most recent U.S. recessions of 2001 and 2007–2009. Because data was readily available, we also compared test scores for poor students (i.e., those eligible for the National School Lunch Program), black, Hispanic, and ELL students. It is important that these types of variables—poverty, race and ethnicity, and language—are taken into account because they are major factors that can impact any analysis of test scores.

The second strongest correlation we found is between the number of school librarians and the reading scores of ELL students, which is likely due to the fact that media specialists serve the special needs of these students with targeted individual tutoring, reading motivation programs, and collection development. But as librarian staffing in school libraries decreases, it’s reasonable to expect that such activities will become rarer or disappear altogether, something that saddens John Schumacher. “If a school doesn’t have a dedicated teacher-librarian, kids will read less and be less comfortable evaluating information,” says the media specialist at Brook Forest Elementary School in Oak Brook, IL. “Kids will have gaps in what they know about technology and how to use it ethically and responsibly.”

Some might wonder if student test scores have less to do with school librarians and more to do with cuts to the overall school staff. But our study also takes into account the percent change in total school staff—including classroom teachers. What we found is that the magnitude and significance of the relationship between librarian staffing and test performance was reduced only very slightly when taking into account overall staff changes in schools (see Table 3). Translation? Whether a school had a librarian remained an important factor in reading test performance, regardless of what was happening with overall staffing numbers.

Just how severe are job losses for school librarians? Data from NCES tell us a lot about the scale of school librarian layoffs—and the pace of these cuts before and during the recession. Between 2004–2005 and 2008–2009, 2,036 school librarian positions were cut across 24 states, and 1,696 positions were added across 24 other states and the District of Columbia, resulting in a net loss of 340 positions or a 0.6 percent decline. (Only Utah reported the same number of school librarians both school years.)

The situation grew dramatically worse between 2008–2009 and 2009–2010, the latest years in which NCES documented librarian positions. During that period, 1,517 school librarian positions were lost across 34 states and DC. This was offset by gains of only 253 positions in 16 states, which resulted in a net loss of 1,264 positions or a decline of -2.3 percent. (Only Arkansas reported the same number of school librarians for the two most recent school years.)

But don’t be fooled. While the raw percentages of school librarian positions lost during the last two years may seem small, they reflect an alarming trend: in one recent year, our nation lost almost four times as many librarians as it had during the preceding four years (-2.3 percent vs. -0.6 percent).

Indeed, we can no longer mask the speed at which media specialists are disappearing. In the last six years, the number of states (including DC) that have axed school librarians has increased by almost 50 percent, from 24 to 35. Meanwhile, the number of states that have gained positions has dropped to 16 from 25—and the number of positions gained has dropped to 253 from an annual average of 424.

Mays says Minnesota has already felt the impact of its losses. Last year, a media specialist in her state’s largest school district, Anoka-Hennepin, agreed to serve four schools—and those that cut librarians were disappointed with their test scores. “As a result, administrators, staff, and students were not getting their critical literacy needs met, and this was conveyed to district-level administrators from several stakeholder groups,” Mays explains.

They got the message. For this 2011–2012 academic year, the district will ensure that no media specialist will serve more than two schools—and in nine schools, teachers, administrators, and students will have a full-time media specialist.

What impact will all this have on student achievement? “Well, it’s difficult to play catch-up,” says Mays. “But check back with me at the end of the school year. I’m certain we’ll see some gains in test scores where media specialists have been returned.”

Despite the fact that our study is based on state rather than local data, doesn’t include data about continuing cuts during the past school year, and doesn’t have more control variables in addition to poverty, race and ethnicity, and language, this is the first direct quantitative evidence that supports the stance that cutting school librarian positions is harmful to students.

Over the past two decades, dozens of studies based on single-year, snapshot data have documented that higher test scores tend to be associated with stronger school library programs led by professional librarians. In the current crisis facing school librarianship, however, these oft-cited studies continue to fall on deaf ears. To address the crisis at hand, more direct evidence is needed to show that school librarian cuts have led to declines in student performance on academic tests—proof that will no doubt further support what we do.

Over the past two decades, dozens of studies based on single-year, snapshot data have documented that higher test scores tend to be associated with stronger school library programs led by professional librarians. In the current crisis facing school librarianship, however, these oft-cited studies continue to fall on deaf ears. To address the crisis at hand, more direct evidence is needed to show that school librarian cuts have led to declines in student performance on academic tests—proof that will no doubt further support what we do.

Lou Ann Jacobs knows better than anyone about the difficulty of advocacy during these tough economic times. As the legislative advocate for the Illinois School Library Media Association, she’s fully aware that libraries and their staff are always among the most vulnerable when there are fewer funds available to schools.

“No doubt, many get discouraged,” says Jacobs. “But this should be the time when we keep up the pressure and talk about student learning and achievement. If we can get through these difficult days, we will be able to prevail.” She tells librarians to contact their legislators to let them know how a bill will affect them and their students—and to always include a personal anecdote about how it ties into student learning and achievement.

It’s not good enough to say children really love coming to the library. Schumacher says he constantly updates his superintendent, principal, colleagues, and even local newspapers, with specific details about his library’s successes and always emphasizes what’s possible when there’s a dedicated teacher-librarian.

Carl Harvey, a school librarian at North Elementary School in Noblesville, IN, and president of the American Association of School Librarians, says his goal is to ensure that his administrator knows more about school libraries than he could ever dream about. That way, he becomes the library’s strongest advocate. “A proactive approach of building a strong relationship with an administrator can hopefully help avoid having to defend a position when there are cuts,” Harvey says.

Unfortunately, administrators must sometimes fail before they realize the importance of a full-time, certified library media specialist on long-term student achievement, says Krista Taracuk, president of the Ohio Educational Library Media Association, which is dedicated to excellence in the state’s library programs. But when library programs are eliminated, it’s the students who suffer the most.

“The greatest impact we’ll see on students as their libraries disappear is the disappearance of the community that a school library creates—not just as a learning environment, but as a place for students to come to meet up with each other, to create together, to find something good to read and have someone there to talk to them about it, a place to be inspired—and then motivated,” says California’s Williams. “Learning just doesn’t happen in a classroom, it needs to be encouraged, supported, directed, and inspired—all those things happen in the strong school library.”

| Author Information |

| Keith Curry Lance consults independently and with the RSL Research Group. He led the research teams that examined the impact of school libraries in Colorado and many other states. Linda Hofschire is a research analyst at the Library Research Service, a unit of the Colorado State Library. |

The data and further research

All data for this preliminary study came from the National Center for Education Statistics. Counts of librarian positions came from the Common Core of Data (CCD), and test scores came from the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

State counts of librarians include librarians at all grade levels. As for all positions tracked by CCD, these counts of librarian positions are based on a definition that specifies what the individual does, not what credentials she or he may have. Thus, it’s impossible to know how many of the librarian positions reported here are state-certified librarians.

In the coming months, we’ll develop this analysis further by incorporating state-level data on more control variables, and, if possible, taking it from the state level to the school-building level. In addition, Colorado—the state that initiated the wave of impact studies over the past two decades—will be the first to attempt to replicate these findings using its own state test, the Colorado Student Assessment Program, and building-level data about changes in both school library staffing and test scores. Conducting such a study at the building level will make it possible to better align data on librarian staffing and reading score variables by grade level, as well as incorporate more control variables.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!