Brace Yourself: SLJ’s school library spending survey shows the hard times aren’t over, and better advocacy is needed

Remember how last year’s spending survey was such a downer? Well, according to the results of our 2010–2011 survey, the picture remains bleak. School librarians, especially those out West, are still struggling to get by on bare-bones budgets. Media specialists are still battling to keep pace with a slew of additional duties—everything from serving as student advisors to maintaining their buildings’ online networks. And although most school libraries’ doors remain open 35 to 40 hours a week..

Remember how last year’s spending survey was such a downer? Well, according to the results of our 2010–2011 survey, the picture remains bleak. School librarians, especially those out West, are still struggling to get by on bare-bones budgets. Media specialists are still battling to keep pace with a slew of additional duties—everything from serving as student advisors to maintaining their buildings’ online networks. And although most school libraries’ doors remain open 35 to 40 hours a week, one-seventh of our nation’s library media centers (LMCs) are open 20 hours per week or less.

On the other hand, since last year’s survey, book collections have grown slightly, media specialists’ salaries in SLJ’s sample have climbed 10%, and perhaps best of all, the worst budget cuts may be behind us. There are also encouraging local signs.

Scores of school librarians who responded to the survey have used these tough times as a clarion call to action. It’s time to “show your staff and students what you can do, don’t just tell them,” wrote a Texas elementary school librarian. “Don’t wait for an invitation. Know the curriculum and how to use it!”

Other media specialists have urged their colleagues to pump up the volume about the key role that school libraries play in boosting kids’ academic achievement. “Speak at school board meetings and community forums,” suggested a Pennsylvania high school librarian. “Get yourself on the schedule to speak to incoming students and their parents. Toot your own horn whenever possible (not something most librarians are comfortable doing, but you have to!). Get on state and local committees to review resources, or review for a journal and let administration know that you’re donating those resources to the library.” Such actions are essential to the profession’s survival during these challenging times.

NOT A PRETTY BUDGET PICTURE

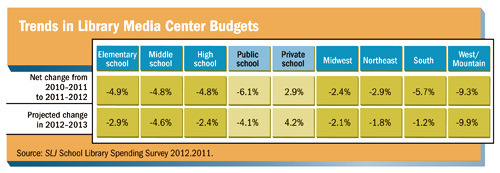

LMC budgets have declined on average since SLJ’s 2009–2010 survey, and media specialists expect even more cuts this year. Those who work in elementary and middle schools reported a dip of 4.8% in their budgets. The situation was slightly better for high school librarians, who reported budget declines of 3.4%. Although budgets are expected to fall in 2012–2013, the cuts aren’t likely to be as deep, with budgets for elementary schools expected to slump by an additional 2.9%, middle schools by 4.6%, and high schools by 2.4%. The picture is brightest in the Northeast, where school library budgets dropped by a comparatively low 2.9%, and dimmest in the West, where they plummeted by 9.3%. Overall, those figures are consistent with trending seen in SLJ’s last couple of spending surveys.

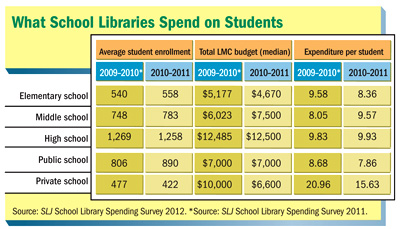

In some areas, private school libraries have outshone public school counterparts. For example, although private schools’ library budgets slipped 2.9%, public schools’ skittered 6.1%. And while public schools spend $7.86 per student annually (down from $8.68 reported in last year’s survey), private schools anted up nearly twice that amount, or $15.63 per student (compared to $20.96 reported the year before).

The bottom line? The median total school library budget was $7,000, ranging from $4,485 in the West to $9,000 in the Northeast, and from $4,670 for elementary schools to $12,500 for high schools. That’s a change from our previous survey, when the median LMC budgets were $5,177 for elementary schools, $6,023 for middle schools, and $12,485 for high schools. The mean figures in our most recent report were sometimes as much as $4,000 higher, indicating that a few LMCs have appreciably deeper pockets than the vast majority of their counterparts. (see the charts on this page.)

As mentioned, most school libraries stay open between 35 and 40 hours a week. But parsing the data yields a less rosy picture: about one in seven LMCs were open roughly half that time or less—and that includes one-fifth of elementary schools and those in the West. And one-tenth of LMCs in middle schools, high schools, and private schools were open less than half the school day. Roughly 80% of LMCs reported no change in hours.

THE STAFFING SITUATION

Salary is one area in which public school librarians came out on top, with the median salary of head public school librarians at $55,000, compared to $43,000 for those in private schools. Dollars-wise, media specialists in the Northeast lead the pack with a median salary of $68,000. And although overall salaries reported this year are up 10 % from the previous survey, middle and high school librarians’ earnings remained flat.

Almost 90% of respondents are full-time credentialed school librarians, although the number dips to 79% at the elementary school level and to 75% in private schools. Almost one-fourth of high schools have two or more full-time school librarians. Part-time media specialists usually worked around 20 hours a week. Compared to the previous year, the professional staffing rate was stable for 94% of LMCs.

In general, there’s a negative correlation between the presence of site-based media specialists and district coordinators, particularly at the elementary school level. A little more than half of public school respondents said they have a district-level library media coordinator or director, with three-fourths of them working full time. Districts in the Northeast and Midwest were least likely to have a coordinator or director (45% and 47%, respectively), while 54% of media centers in districts in the West and 70% of those in the South had one.

As for support staff, about one-third of LMCs have a full-time clerk (about 4% have two), with the positions mostly found in the Midwest (49%) or the South (44%). Media centers in the West (43%) and Northeast (38%) are more likely to employ a part-time clerk or aide, and private schools are the least likely to have one.

As a result of budget cuts, many school librarians have turned to adult volunteers for help. Overall, almost half (about 46%) of LMCs have adult volunteers, and two-thirds of elementary schools and three-fourths of private schools have an average of five and six volunteers, respectively. Only one-third of middle schools and a quarter of high schools have adult volunteers, since students’ parents often aren’t as involved in the upper grades. Three-fourths of school libraries saw no change in volunteer trends, but the remaining quarter experienced a net increase, particularly in the Midwest (23%) and middle schools (22%), where they’re finding alternative ways to staff the media center.

As student volunteers go, the usual patterns persisted: one-third of elementary schools, two-thirds of middle schools, and almost three-fourths of high schools use student helpers. Elementary schools averaged three volunteers, and middle and high schools twice that number. Only one-third of private schools had student volunteers (and averaged just two students), probably because the responding schools serve mostly younger students.

In terms of regional representation, about two-thirds of Western LMCs have student volunteers, compared with 56% in the Northeast and South, and 45% in the Midwest. But the average number of student volunteers per region reflected a different pattern, with a mean of three helpers in the Midwest, four in the West, and five in the Northeast and South.

FEELING S-T-R-E-T-C-H-E-D?

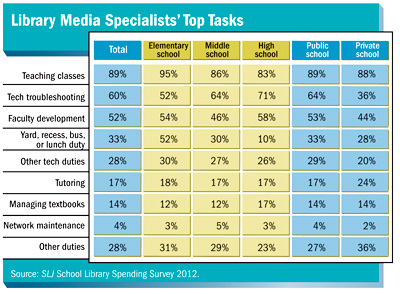

Lean budgets and worries over possible layoffs have prompted many school librarians to volunteer—or administrators have asked them to “volunteer”—for additional duties. On the bright side, some new duties also stretch the potential impact of the person in the role. For instance, media specialists now routinely teach classes: about 89% say they offer instruction, although it’s unclear if they’re teaching traditional library classes or classroom courses. Elementary school librarians tend to teach the most (95%) and those in high schools the least (83%). About a sixth of librarians also tutor students, with roughly 24% of private school librarians leading the way. When it comes to tutoring, there are also significant regional differences, with only 6% of Midwest media specialists offering that type of instruction, compared to 17% in the Northeast, and a robust 22% in the South and 23% in the West.

Overall, 60% of survey respondents also engage in technology troubleshooting, including 52% of elementary school librarians, 64% of middle school media specialists, and 71% of those in high schools. Interestingly, only a third of private school media specialists handle that task, compared to two-thirds of their public school counterparts. About one-quarter of school librarians also had other tech responsibilities, especially those in the South (about a third). Again, private school librarians—approximately one-fifth—are least likely to have additional tech duties on their plates. (See the chart below for more information.)

Slightly more than half of all media specialists conduct professional development programs—although that percentage sinks to 44% in private schools.

On the downside, some new duties retract the impact of the role. For instance, as one might expect, elementary school librarians (52%) are at the top of the heap when it comes to covering playground duty or breaks—which makes us wonder how their media centers can possibly remain open during those times! Only 28% of private school librarians, who tend to work in K–8 schools, were responsible for supervising the playground and break times. About a quarter of school librarians also reported doing “other duties as assigned” (such as monitoring study halls, leading book fairs, and supervising morning announcements), particularly those in the South and in private schools (approximately one-third for each group). While it may appear that private school librarians are getting off a little easier—with more narrowly defined roles—than public school librarians, they’re actually assuming many new duties that aren’t traditionally associated with media specialists, such as serving as student advisers.

When asked for advice on how librarians can enhance their value as educators, many respondents mentioned the need to keep up-to-date with new developments, especially with the latest advances in technology. Several also encouraged librarians to learn about grants and how to write effective ones. Others brought up the importance of engaging in professional development opportunities (both at school and in professional associations) and staying current with the professional literature. Still other media specialists stressed the need to be proactive. “Find ways to become integrated into every course in the building,” urged one school librarian. “Show your administrator what you are doing and how it reflects on student data. Make yourself the go-to person.”

Another set of suggestions focused on sharing resources and forming partnerships, including networking with a variety of stakeholders, sponsoring book exchanges, and encouraging interlibrary loans. Respondents also urged libraries to host parent meetings, reading programs, and tutoring sessions. Some respondents reminded their peers to seek community sponsors for events and cultivate volunteers for the library. Several librarians also noted the need to volunteer for extra responsibilities, such as coordinating online learning and credit recovery programs.

Good old-fashioned competition also has a role to play, some noted. “Talk to other teacher-librarians in your state and find out how they got books, technology, etc. and formulate your own plan,” recommended a Rhode Island librarian. “Don’t be afraid to use a community’s sense of healthy competition. For example, ‘Town A has X and we don’t. How do you feel about those children having a resource that our children don’t? How can we work together to level the playing field?’”

CALLING ALL COLLECTIONS

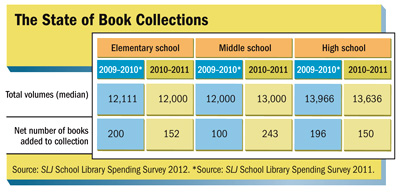

Historically, the size of a school library’s book collection has correlated positively with grade level and student enrollment. Elementary school LMCs have roughly 12,000 books on their shelves, middle schools offer around 13,000 titles, and high schools weigh in with 13,636 titles. Public school libraries edged out private, with an average of 12,500 volumes to 11,000, respectively. On the whole, book collections grew slightly, with a net increase of 200 titles each. (See the above chart.)

The picture of LMCs’ book expenditures is more varied. The median total book budget was $5,000, with elementary schools spending $4,500 in contrast to middle and high schools, which each laid out $6,000. Private school libraries dished out a median of just $3,342, compared with $5,061 by public schools.

What was the average expenditure per pupil? The total for all school libraries was $11 per student, which varied from $8 at the elementary level to $10 at the high school level, and ranged from $10 in the Midwest to $5 in the West. Private school libraries doled out $16 for each student, and public schools spent half that amount.

Reference collections have continued to shrink, probably because school librarians have reclassified many of these books as general circulating items and now put a greater emphasis on using subscription databases. Nevertheless, relative to the total collection, things are surprisingly stable. Although one to two percent of LMCs don’t have a reference collection, the vast majority do: elementary schools have a median of 100 volumes, middle schools 400, and high schools 1,000. LMCs in the Northeast had a median of 314 reference books, followed by those in the South with 280, the Midwest with 250, and the West with a scant 200 volumes.

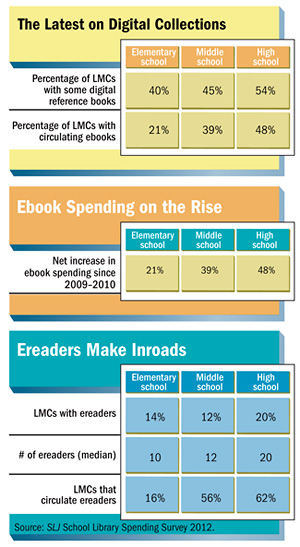

How many of those reference titles are digital? On average, about 6%. Surprisingly, the majority of LMCs don’t have any digital reference works. Private schools boast an average of 9% digital reference books, compared with 6% for public schools. Elementary school collections average 5%, middle schools 7 %, and high schools 8%. Among high schools there was a huge swing: 3.5% had reference collections in which the majority of titles were in digital format—and 50% of high schools didn’t have a single digital reference title. The digital divide yawns. (See “The Latest on Digital Collections” on p. 42.)

HEY, WHERE ARE THE EBOOKS?

Although digital books may be the rage, school libraries have been slow to join the party. About two-thirds of LMCs don’t have any circulating ebooks—ranging from four-fifths of elementary schools to about half of high schools. The difference between the mean (average) and median (the half-way point) was startling: an average 1,277 ebooks, with 1,281 for elementary schools, 763 for middle schools, 1,741 for high schools, with a median of just 50 items. Nevertheless, overall spending for ebooks rose an average of 8% over the previous year, with the greatest gains (around 14%) in high school libraries and in the Northwest and Midwest. Ebook spending was pretty much flat in middle schools, the South, and the West. (See the above chart on ebook spending.) To learn more about e-books in school libraries, check out Library Journal and School Library Journal’s 2011 ebook penetration and use survey.

Where are media specialists buying them? Fifty-seven percent of ebooks come from Follett, with Gale/Cengage a distant second at 24%. About 11% of school libraries order directly from publishers, and other sources include NetLibrary and Barnes & Noble (8% each), Amazon (6%), OverDrive (4%), and public domain materials or other digital resources (28%).

How about ereaders? A full 84% of school libraries don’t have any. For those LMCs fortunate enough to own some, the median number of digital devices is 12 (ranging from 10 in elementary schools to 20 in high schools). Not surprisingly, 84% of elementary school libraries that do have devices don’t lend out their ereaders, while half of middle schools and two-thirds of high schools and private schools circulate their devices. (To learn more, see “Ereaders Make Inroads” on the left.)

The overall budget for ebooks remains small: an average of $275. Two-thirds of that money came from local school board appropriations, another fifth came from federal funding, and the rest from local fund-raising efforts and gifts. Elementary schools and Western LMCs fared the worst (spending less than $70 on average for ebooks), while private school LMCs did the best, with an average of $388 spent on digital titles.

As for the most popular ereaders, Nooks are the preferred choice in 50% of LMCs, with Kindles and iPads running neck and neck at about 40%, and Sony’s ereader bringing up the rear at 9%. About half of high school libraries that have ereaders own Kindles and/or iPads—with iPads the clear-cut favorite in private schools by a 2-to-1 margin.

Even with money to burn, however, without the necessary infrastructure and hardware, ebook adoption remains purely a dream. One New York City elementary school librarian seemed to sigh as she wrote, “The reason I can’t buy ebooks is that the computers in my library are so old that the web browsers don’t load ebooks. The web browsers can’t be updated until the operating systems on the computers are updated. That’s why, even though I have $15,000 to spend from the Robin Hood Foundation, I spend $0 on ebooks; no one will replace my computers. In such a high-poverty area, very few of my students have computer access at home either.”

DIGITAL, BEYOND BOOKS

Sixty percent of LMCs spent money on web-based information resources, averaging $1,509. Predictably, high school libraries racked up the biggest bill, averaging $3,259. Librarians in the Northeast and in private schools were also among the biggest spenders at $2,409 and $2,009, respectively. As expected, elementary school libraries were the most frugal in this category, spending just $373. More than 90% of the funding for online information resources came from local school boards.

Media specialists aren’t spending much on audiovisual goods and services, such as CDs, DVDs, video players, digital cameras, camcorders, SMART boards, PDAs, and cable video streaming. The average amount they plunked down on these items was $510, with two-thirds spending a median of $100, with roughly 90% of those dollars coming from local schools and districts. Curiously, librarians spend slightly more on the equipment needed to support AV—an average of $668—than on the audiovisual products themselves.

Media specialists aren’t spending much on audiovisual goods and services, such as CDs, DVDs, video players, digital cameras, camcorders, SMART boards, PDAs, and cable video streaming. The average amount they plunked down on these items was $510, with two-thirds spending a median of $100, with roughly 90% of those dollars coming from local schools and districts. Curiously, librarians spend slightly more on the equipment needed to support AV—an average of $668—than on the audiovisual products themselves.

About 56% of LMCs purchased an average of $594 of computer software—although most libraries within that group spent a miniscule amount, typically less than $200. Interestingly, the West fared the best, spending an average of $974 on software (most likely on reading programs), and far outdistancing Midwest LMCs, which laid out an average of $358. Local school boards accounted for roughly 83% of the funding, with another 5% coming from federal funds, and the balance from fund-raising activities.

School librarians are also reconsidering the desktop computer. On average, LMCs purchased just one desktop machine in 2010–2011, and 9 times out of 10, they used nonlibrary funds to buy it. Media specialists plan to purchase the same number of desktops this year, which probably means they’re just replacing existing machines. However, the other reason for the tiny number of desktop acquisitions is the rise of laptops and notebooks in LMCs: an average of 2.6 (two in elementary schools, the South, and the West, compared to six in the Midwest LMCs). As with desktops, laptops are also bought with nonlibrary funds more than 90% of the time, and LMCs anticipate buying only one or two laptops this year.

Tablets are also beginning to hit the scene, with LMCs likely to own one or two wireless devices. Most school libraries bought a tablet in 2010–2011, and they expect to buy another one this year, using nonlibrary dollars.

Computer hardware was purchased by 56% of LMCs, averaging $1,182 per site. About two-thirds of the funds came from local school boards; federal funding accounted for about 10%, and the rest was fund-raised. Private LMCs spent only an average of $617, elementary ($776), and Western ($780). LMCs also spent relatively little in comparison with high schools ($2,048).

AN ETHICS DISCONNECT

AN ETHICS DISCONNECT

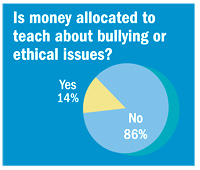

If money talks, it’s tough to tell if schools really value ethics and digital citizenship. Less than five percent of LMCs set aside funds for digital-citizenship speakers or programs. Elementary school libraries (5%) were a little more likely than middle and high schools (3% each) to promote these programs. Private school LMCs (19%) were much more likely to allocate fund to teach ethics and digital citizenship than those in public schools (about 3%).

Interestingly, almost 11% of school libraries used some kind of plagiarism software—about 7% of those in the Northeast and West and 3% in the Midwest and South. A strong positive correlation exists between plagiarism software and faculty workshops, which may imply that curative rather than preventative measures are being taken relative to intellectual property issues. A case could also be made that faculty concerns, such as worries about plagiarism, drove this funding support.

GET READY, GET SET, ADVOCATE!

Numbers, although important, tell only part of the story. When survey respondents were asked to write down a single piece of advice they’d like to share with their colleagues, the number one suggestion was: Hang in there! The second most popular piece of advice: Advocate, advocate, advocate! Advocacy is an essential part of being a 21st-century librarian—and not just for our own sakes, but for the sake of our students, our programs, and the teachers we work with. To that end, one media specialist encouraged her colleagues to take advantage of SLJ, the American Association of School Librarians (AASL), and other sources of professional advocacy materials. (SLJ has just launched an advocacy blog, “Make Some Noise!,” by former AASL president Sara Kelly Johns.) Several respondents also urged peers to increase their visibility and tell the library story to stakeholders including other educators, administrators, parents, and school boards.

Be ready to provide compelling evidence of how school libraries enhance student learning. It also never hurts, especially around budget or contract-renewal time, to have quantitative records of library usage (including records of circulation, individual and class visits, and space use), lessons taught, time spent on technology, staff requests, and student programs, links to library materials that support the school curriculum, evidence of the impact on student achievement, and a record of the increased cost of materials, items lost, extra duties performed, and tasks that can’t be done because of limited staffing or funds. Don’t be afraid to “rock the boat,” advised a Kansas high school media specialist adding that, “If budgets are cut, services must also be cut to prove what is necessary.”

Remember, noted others, that it helps to keep things in perspective. “I’ve been a teacher-librarian for 28 years and budgets have been restrained for about 22 of those years,” wrote a California middle school librarian. “We’re always fighting for funding and recognition. Just remember that by working with students every day, we help educate them and assist them in becoming their best selves. No matter what the current fiscal crisis, we still foster in our students the love of reading, learning, and doing research. That makes all we do worthwhile.”

| Author Information |

| Lesley Farmer (lfarmer@csulb.edu) coordinates the librarianship program at California State University Long Beach. |

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!