Reading Around the World

Ranging in subject matter from folklore-style offerings to tales that touch upon more serious issues, these titles have been chosen for their ability to evoke a specific setting or culture while revealing universal themes.

Encourage kids to explore other places and ways of life with this round up of recently published picture books set across the globe. Ranging in subject matter from slice-of-life stories to folklore-style offerings to tales that touch upon more serious issues, these titles have been chosen for their ability to evoke a specific setting or culture while also revealing universal themes. Arranged geographically, the tales can be shared with students to introduce studies of cultures and countries, or to foster a sense of global community. Through these picture books, children will learn about the lives of other people, discover similarities and differences, and develop both self-awareness and empathy for others.

The Broad View

The Broad View

In This Is How We Do It (Chronicle. May. 2017; K-Gr 4), Matt Lamothe provides a glimpse at how children from seven countries go about their daily lives. Based on real kids (from Italy, Japan, Peru, Uganda, Russia, India, and Iran), the themed spreads combine charming illustrations and brief text to introduce topics such as living accommodations, foods, favorite pastimes, household chores, and dinner customs. General statements (“This is what I do in the evening”), encourage readers to add their own specifics to each scenario, make comparisons, and identify similarities and differences. Each child is pinpointed on an endpaper map, and a glossary and photos of the featured families are appended. Baptiste Paul and Miranda Paul’s Adventures to School (Little Bee. May. 2018; Gr 1-5) illustrate the various modes of transportation utilized by children around the world. Illustrated by Isabel Muñoz, bright spreads show a child riding a teleférico (cable car) from one mountain-top city to another in Bolivia; youngsters climbing down a sheer cliff on a “heaven ladder” in Sichuan Province, China; a girl braving the rain during a three-hour trek along steep mountain roads in Samdrup Jongkhar, Bhutan; and other scenes. Supported by additional facts, these fictionalized vignettes will spark curiosity about the featured locales and underscore the characters’ passion for seeking an education.

Africa

Students can begin their journey by exploring gems of human wisdom From the Heart of Africa (Tundra, Jan. 2018; K-Gr 5). This handsome volume, compiled by Eric Walters, gathers together 15 astute aphorisms from a variety of African peoples and regions, each presented in large text along with a source note and stunning full-page illustration. Interpretations of each saying are also included, helping readers to put meaning into context and broadening the age appeal of the book. Some maxims will be familiar, such as “Many hands make light work” (from the Haya people of Tanzania) or “It takes a village to raise a child” (the Igbo and Yoruba peoples of West Africa), underscoring the universality of the human experience. Ranging from more traditional interpretations to the more abstract, the enchanting illustrations showcase an array of styles and add additional layers of meaning. “Children are the reward of life” (Bakongo people of Central Africa) is paired with French Canadian artist Rogé’s sepia-hued portrait of a smiling boy, while “Traveling is learning” (Kikuyu people of Kenya), features Sindiso “R!OT” Nyoni’s (an artist born and raised in Zimbabwe) comic-book-style image of a female astronaut. Use this book as an entrée point to explore the various countries and cultures represented, encourage discussion of the aphorisms and their meanings, and highlight insights into the commonalties we all share.

Wanuri Kahiu’s The Wooden Camel (Lantana, 2017; K-Gr 4) features Etabo, a Turkana boy who lives in northwest Kenya, where he dreams of becoming the best camel racer ever. However, as the price of water rises and the family’s financial situation worsens, the camels must be sold, Etabo’s older siblings are forced to find work, and he is left to tend their goats alone. Praying to Akuj the Sky God for help, Etabo is told, “Your dreams are enough.” These repeated words of wisdom, along with a thoughtful gift from his sister Akiru—a herd of hand-whittled wooden camels—eventually help to restore the boy’s hope for the future. Manuela Adreani’s flowing paintings depict sweeping grasslands and expressively depicted characters. This tale of family affection and the power of resiliency ends with Etabo tucked into bed, “clutching his new best friends,” while his dreams soar.

Based on a real school in Mtwapa, Kenya, Patricia Newman’s fictional story introduces a young girl who dreams of getting an education but whose family is unable to afford the high cost of uniforms and supplies. Walking to town to sell her basket of fruit one day, Neema spies another girl and follows her to a classroom, where she meets a teacher who is determined to help her fulfill her goals. Engagingly told in an accessible first-person narrative, Neema’s Reason to Smile (Lightswitch. May. 2018; PreS-Gr 4) is illustrated with Mehrdokht Amini’s lovely collage-style artwork, which shimmers with verdant colors and eye-catching patterns. Backmatter includes quotes and photos from actual Jambo Jipya students, discussion questions and activities, and a note on the book’s origins.

Also illustrated by Amini, Nnedi Okorafor’s Chicken in the Kitchen (Lantana, 2017; K-Gr 4) stars another resourceful female protagonist. It’s the night before the New Yam Festival in Nigeria, and Anyaugo is awoken by a strange noise. The girl quietly creeps toward the kitchen, where she discovers a giant-size bird with spectacular, bright-hued feathers. Worried that this uninvited visitor will spoil the food her mother and aunties had prepared for the harvest celebration, she asks for help from the Wood Wit, a nature spirit that lives in the wooden walls of her house. However, as readers who look closely at the illustrations will suspect, the Wood Wit might be a bit of a trickster. Could the mysterious chicken be one of the powerful masquerade spirits that visit “the community during festivals, ceremonies and events”? It will take all of Anyaugo’s courage and cleverness to discover the truth. Lively text and vibrant artwork serve up a glimpse at this festival along with a playful perspective and bit of suspenseful adventure.

Nigerian storyteller Atinuke uses rhythmic text and sensory details to describe what happens when Baby Goes to Market (Candlewick, 2017; PreS-Gr 2) in a bustling community in West Africa. Tied onto his mother’s back with a colorful wrap, this charismatic tot charms wares from a variety of vendors, tasting a bit of each treat and then adding the remainder to the wide-brimmed shopping basket his mother balances on her head. “Market is very crowded./Baby is very curious./Baby is so curious that/Mrs. Ade, the banana seller,/gives baby six bananas…Baby eats one banana…/and puts five bananas in the basket.” Before long, Baby has accrued four juicy oranges, three sugary chin-chin biscuits, two roasted sweet corn, and one piece of coconut. Young readers will chuckle along as Mama, busy with her shopping, remains oblivious to Baby’s activities until story’s end, when all is revealed and a taxi is hired to take them home. The buoyant language is as irresistible and Angela Brooksbank’s bright-hued, mixed-media illustrations delightfully depict the setting and echo the lighthearted humor.

Americas

The Field (NorthSouth, Mar. 2018; K-Gr 4), an open space on a lush Caribbean island, calls to a group of children who set up goals made from bamboo, chase grazing cattle away, choose teams, and begin an energetic soccer match. When “Shutters bang./Sun hides./Clay dust stings./Sky falls,” it looks like the game might be over, but the determined athletes kick off their shoes and play on, slip-sliding, belly-flopping, splash-dashing until the weather clears, the sun begins to set, and Mamas call everyone home. Baptiste Paul sprinkles this rhythmic ode to fútbol with Creole words from his native Saint Lucia (defined along with pronunciation guide at book’s end) and Jacqueline Alcántara vivid paintings reflect the youngsters’ exuberance, passion for the game, and joy in spending time together.

In Cuba, a boy and his parents load cake and gift into their old car to drive All the Way to Havana (Holt, 2017; PreS-Gr 4), where they will celebrate the birth of a new baby. Like many of the island’s pre-1959 American automobiles, Cara Cara has been lovingly repaired and inventively jury-rigged to last through the decades. Today, however, her usual chicken-like cacophony (“cara cara, cara cara,/cluck, cluck, cluck” ) is sounding a bit diminished (“Pío pío,/pío pío,/pfffft”). Never fear, Papá pulls out his toolbox, and after some tenacious tinkering, soon has the 1954 Chevy ready to go. Margarita Engle’s rhythmic text and Mike Curato’s charming mixed-media artwork convey a strong sense of place and offer a family adventure teeming with sweet affection and the spirit of perseverance and ingenuity.

Set in a fictional river town in Brazil, Eymard Toledo’s picture book is narrated by a boy who spends the afternoons with a loving relative while his mother works at a nearby factory. Uncle Flores is The Best Tailor in Pinbauê (Triangle Square, 2017; Gr 2-5), and Edinho enjoys helping him while listening to his stories about the history of the town, and how things have changed since the factory was built (growth and pollution have left the water of the Velho Chico polluted, fishermen without fish, and everything covered in gray dust). Now his uncle only sews gray factory uniforms, and then loses even that contract when cheaper clothing is flown in from abroad. When the boy finds colorful material once used for “beautiful dresses and fancy suits” stowed away in a drawer, he comes up with an idea to restore his uncle’s business as well as the heart of his town. Handsomely illustrated, this intergenerational story shines light on themes of family, community, ecology, and changes wrought by industrial development, and ends on a hope-filled note.

Written by two Latin American collaborators and originally published in a Spanish Language edition, Jairo Buitrago and Rafael Yockteng’s Walk with Me (Groundwood, 2017; Gr 1-5) provides a thoughtful, emotionally powerful glimpse at the day-to-day difficulties faced by a child whose living situation involves an absent parent. Offering a simple flower, a girl asks an intimidating lion to accompany her on her way home from school. As adults react in fear (and children with excitement), the pair wend their way through city streets, pick up her baby brother from daycare, buy food at a store “that won’t give us credit anymore” (except when there’s a lion to roar at the shopkeeper), and prepare and share a meal in a spare apartment in need of repair. When their tired mother gets home from work, the girl releases the lion back to the hills, with the reminder to “come back when I call.” In a family portrait displayed on the final spread, the father’s bushy hair resembles the mane of a lion (the flower rests in front of it), encouraging readers to think more deeply about the child’s family situation, and offering opportunity to provide context. Dusky illustrations satiate the understated first-person narration with detail and atmosphere, creating a poignant tale worthy of discussion.

Canada

Shauntay Grant’s lyrical text and Eva Campbell’s lovely oil paintings offer a child-eye’s view of Africville (Groundwood, Sept. 2018; K-Gr 4), a Black community once located in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The first-person narration features a modern-day girl looking back in time, witnessing nostalgic scenes of outdoor activities (picking blueberries, rafting on Tibby’s pond, a summer evening bonfire at Kildare’s Field) and special family moments. The pages radiate a strong sense of history and community—paying tribute to a place “where memories turn to dreams,/and dreams turn to hope,/and hope never ends.” An author’s note explains the roots of Africville (it was settled by Black Loyalists who migrated during the American Revolutionary War and refugees who fled enslavement during the War of 1812), the fact that the town was denied equal services through the years yet remained a “vibrant, self-sustaining community,” and the forced relocation of residents when officials demolished it in the 1960s. Annual reunions on the site have been held since 1983, providing the framework for an evocative book that brings a unique, vibrant community to life.

In Joanne Schwartz and Sydney Smith’s Town Is by the Sea (Groundwood, 2017; K-Gr 4), a boy describes a summer’s day in a Cape Breton mining town in Nova Scotia during the 1950s. His sparkling-with-light activities—playing with a friend at an “old rickety playground,” a baloney sandwich lunch back at home, a walk over to the Main Street grocer for his mom, a visit to the grave of his grandfather (also a miner)—are juxtaposed with those of his father, who toils “deep under the sea, digging for coal,” black layers of textured rock seeming to weigh heavy atop a narrow lamp-lit tunnel. “One day, it will be my turn. I’m a miner’s son. In my town, that’s the way it goes.” Eloquent text filled with sensory details and beautiful brush-stroked artwork paint a telling portrait of a way of life and a moment in history.

David Alexander Robertson and Julie Flett provide a Cree heritage story that touches upon the history and legacy of Native American residential schools. Spending time with her grandmother, a girl asks, “Nókom, why do you wear so many colours?” or “why do you wear your hair so long?” The woman explains that as a child, she was sent to a school far from home, where she and other youngsters were forced to wear dull colors and have their hair cut short. But When We Were Alone (Highwater Pr., 2016; K-Gr 4), Nókom explains, they piled autumn-hued leaves over their clothing “to be colourful again,” or braided blades of grass into their hair to make it long again—always trying to hold close the way of life they left behind. Using this questing-and-answer format, the text reveals how residential schools tried to enforce conformity and separation from family; more impactfully, the narrative highlights the ways these resilient children managed to cling to their cultural identities, and aspects of daily life that Nókom now celebrates every day. Presented with a deep sense of empathy and illustrated with lovely collage artwork, this book introduces a harrowing topic in a manner accessible to young children, while also celebrating the strength that comes from family and cultural traditions, and creating a mood of empowerment and hope.

Southern Asia

Southern Asia

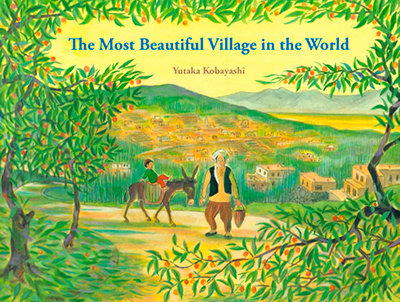

Yutaka Kobayashi’s lush paintings and flowing narrative depict a fictitious town in Afghanistan. Summertime has brought a bounty of fruit to The Most Beautiful Village in the World (Museyon. Sept. 2018; K-Gr 4), but this year, Yamo’s older brother is not there to help with the harvest; there is war in their country, and Haroon is now a soldier. When Yamo accompanies his father to town to sell their produce, the day is filled with the excitement of unfamiliar sights and sounds, but the shadow of war is ever present—in conversations with townsfolk, and in illustrations that often include images of men patrolling with machine guns. Father and son sell all of their wares, and their homecoming is filled with hope for Haroon’s return next spring. Abruptly, and affectingly, the final, text-only page reads: “In the winter, the village was destroyed in the war. It no longer exists.” Detailed paintings create a strong sense place, a mood of warm family affection, and an appreciation for what once was. This book opens readers’ eyes to the devastating losses that result from war.

India

Chitra Soundar and Kanika Nair follow their delightful Farmer Falgu Goes on a Trip (2016) with a second tale set in rural India. This time, Farmer Falgu Goes to Market (Karadi Tales. Apr. 2018; PreS-Gr 4) after loading his brightly painted, oxen-drawn cart with tomatoes, onions, green chilies, cilantro, and eggs. Unfortunately, there are some unexpected bumps along the road (everything from potholes to errant duck crossings), resulting in cracked eggs and squashed vegetables, but the optimistic—and resourceful—protagonist figures out the perfect solution to guarantee a successful day. Utilizing bold lines, earth tones, and splashes of color, the energetic artwork provides just enough detail to convey the lively action and locale. Filled with ear-pleasing rhythms and onomatopoetic language, this picture book is engaging and fun to read aloud. Share this along with Farmer Falgu Goes on a Trip (2016) with students to discuss the folklore-style telling and launch explorations of the setting.

Set in a village in eastern India, Mina vs. the Monsoon (Yali. Dec. 2018; K-Gr 4) introduces a soccer-loving protagonist who is determined to chase away the gray weather so that she can get outside and shoot goals. Though her ammi (mother) and the doodh wallah (milk man) point out the benefits of the rain, impatient Mina still tries everything—playing the tabla (a percussion instrument), dressing in a red-orange shalwar kameez (“a traditional outfit consisting of a long tunic, a scarf and loose pants”) to perform a dance, and even a bit of made-up magic (with the help of her elephant toy)—to chase away the clouds. However, it takes an unexpected discovery (Ammi’s folded-away soccer jersey) to both reinforce a close family relationship and turn the day around. Urdu and Hindi words are woven into Rukhsanna Guidroz’s accessible text (and defined along with a pronunciation guide at book’s end). Devasmita Dasgupta’s vibrantly hued illustrations (featuring charismatic characters with expressive windowpane eyes) are filled with emotion and action. Both words and pictures provide context for the book’s cultural and geographic setting while revealing universal themes.

It’s springtime in India, and siblings Chintoo and Mintoo enthusiastically prepare for Holi, Festival of Colors (Beach Lane. Jan. 2018; PreS-Gr 4). “Holi, hai” (“It’s Holi”), they whisper, as they gather fresh flowers from a lushly blooming garden (effervescent full-bleed spreads reveal that “hibiscus flowers make red,” “orchids make purple,” etc., and encourage reader participation). The blossoms are then dried in the sun, separated into petals, and pressed into fine powder. When all is ready, the youngsters’ family, friends, and neighbors—all clothed in white—head outdoors, where the powders are tossed, and with a repeated “POOF!— colors explode in a joyous celebration. Now covered in rainbow splatters, the smiling participants return home to commemorate a “festival of fresh starts./And friendship./And forgiveness…[and] fun!” Kabir Sehgal and Surishtha Sehgal’s short, accessible text and Vashti Harrison’s cinematic-style illustrations draw readers into the action, providing a brief introduction to this festival while also depicting a strong sense of family and community.

Margarita Engle, Amish Karanjit, and Nicole Karanjit take readers to Nepal to introduce A Dog Named Haku (Millbrook. Sept. 2018; Gr 1-4) and the five-day Hindu festival known as Swanti, Tihar, or Deepawali (Diwali or Deepavali in India). Thinking back to the earthquake that had struck Kathmandu in the spring, and the search and rescue dogs that worked tirelessly to help locate those trapped in the rubble, brothers Alu and Bhalu are determined to find a “stray dog—a kukur—/to honor with food/and gratitude.” They roam the city, but it’s not until evening that they find a puppy on a dark corner, “wandering/homeless,/motherless,/lonely.” Naming her Haku (black) for her soft fur, they bring her home, where she is fed festival treats, draped with garlands of orange flowers, and eventually accepted into the heart of their extended family. Ruth Jeyaveeran’s illustrations, done in dusky hues with bright splashes of pattern and color, convey the setting and the characters’ emotions. Sprinkled with Nepali words (glossary appended), the lyrical text grippingly describes the boys’ adventure (inspired by Amish Karanjit’s boyhood experiences) and expertly blends cultural traditions with intimate family moments.

Eastern Asia

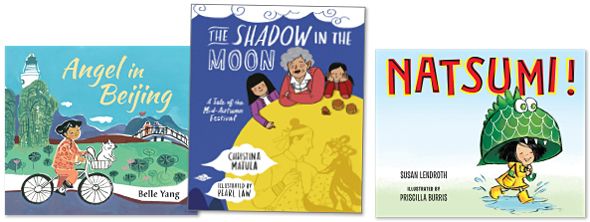

Belle Yang’s Angel in Beijing (Candlewick. Jul. 2018; K-Gr 4) showcases modern-day life in a city in China, as a girl goes in search of a missing pet. Startled by a firecracker on New Year’s Eve, the fluffy white cat ends up cowering in a gingko tree in the narrator’s courtyard, and the two quickly becomes inseparable. As the girl bicycles around the city, Kitty contentedly rides in a basket, answering each “Trrring-trrring” of the handlebar bell with a “ Niaow-niaow.” During a trip to Tiananmen Square on the day of the Dragon Boat Festival, Kitty chases after an enormous dragon kite, is lifted into the air, and disappears from sight. Her heart “down in [her] shoes,” the youngster searches everywhere, visiting both historic sites and quieter backstreets; days pass, and she gives up hope. Then, while riding through an alley, the sound of her bell is unexpectedly answered. Pushing open a gate, she finds Kitty, now in the care of lonely old lady, and makes a difficult decision…along with a new friend. The first-person text and lovely, gouache paintings provide a vivid look at life in Beijing while telling a tender tale.

A family dinner during the Chinese Mid-Autumn Festival, when “the moon is biggest and brightest,” provides a framework for Ah-ma to tell her granddaughters the legend of The Shadow in the Moon (Charlesbridge. Jul. 2018; K-Gr 4). Long ago, a brave archer named Hou Yi saved his people from the blazing heat of 10 suns by shooting nine of them, and was rewarded with a magic potion of immortality. His wife, Chang’e, courageously swallowed the potion to prevent it from falling into the evil hands of a thief, and become the Spirit and Lady in the Moon. Realizing her fate, Hou Yi honored his beloved by putting out her favorite foods, including round cakes. Today, mooncakes serve as a remembrance of “two brave souls whose courage gave us peace and harmony between the heavens and the earth.” Sated by both story and food, the young narrator contemplates all that she is thankful for, including her family, and makes a wish for the coming year “to be kind of heart and wise of mind.” Illustrated with Pearl Law’s colorful artwork, Christina Matula’s engaging holiday tale ends with an author’s note and a recipe for mooncakes with red-bean filling.

Natsumi! (Putnam. Mar. 2018; PreS-Gr 3), who lives in Japan, does “everything in a big way”—splashing through puddles, tearing through the park, slamming doors, and slurping noodles “like a sumo wrestler.” As her village prepares for a festival of tradition arts, she over-enthusiastically shakes the bouquet of flowers she is arranging with Grandmother (resulting in a “cloud of pollen, leaves, and ants”), whirls tea leaves “into a cyclone” during the tea ceremony with Father (splattering his glasses), and inadvertently launches her fan across the room during dance rehearsal with Mother (while pretending to lead troops into battle). Never fear, her supportive grandfather helps her find the right fit for her exuberant nature—becoming the youngest member in a troop of taiko drummers. Susan Lendroth’s lively text, filled with fun-to-read aloud rhythms and sound effects, and Priscilla Burris’s dynamic spring-hued artwork, deftly incorporate aspects of Japanese culture and setting while telling a tale that will have universal appeal for misfits—and budding individualists—everywhere.

South-Eastern Asia

South-Eastern Asia

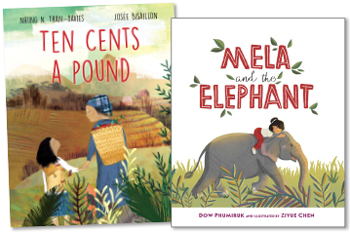

In Ten Cents a Pound (Second Story Pr. Apr. 2018; K-Gr 4), Nhung N. Tran-Davies, whose family came to Canada as refugees from Vietnam in 1979, shares a story of familial love, sacrifice, and finding the courage to dream big. A young girl longs to go to school and get an education, but is reluctant to leave her mother and her mountain village behind. The woman works in the coffee fields, and the girl worries about Mama’s “coarsened and scratched” hands, “calloused and blistered” feet, stooped-in-pain back, and “blurred and strained” eyes. Each time the girl declares that she will stay, her mother insists that she must go, repeating the phrase, “Ten cents a pound is what I’ll earn,” money that will allow her daughter to find a better life. Switching back and forth between the two characters, the lyrical first-person narrative shines with eloquence and emotion. Josée Bisaillon’s handsome paintings depict a realistic setting along with a breathless sense of wonder. In the end, the child agrees to go but promises to return, and the final image—a closeup of their two hands, fingertips touching with a coffee blossom between them—is both powerful and poignant.

Set in a village in northern Thailand, Dow Phumiruk’s Mela and the Elephant (Sleeping Bear Pr. Mar. 2018; K-Gr 4) blends folktale-style action with a moral message to convey a modern-day fable. When Mela sets out to explore the banks of the Ping River, her little brother wants to come along. “What will you give me if I take you?” she asks, but he has nothing to offer and is left behind. Boarding her uncle’s tiny boat, she is swept downstream. Lost and alone, she asks for help getting home from various jungle animals. However, a crocodile, a leopard, and monkey trio all snatch their promised rewards without providing any aid. Now in tears, Mela is carried home by a generous elephant, which requires nothing in return, a lesson in kindness that she pays forward to her brother the very next day. Ziyue Chen’s eye-catching digital artwork depicts the action and the setting with lush greens and flowing lines. An author’s note provides an intro to Thailand and its customs. This book makes a wonderful launch point for exploring Thai culture, and making comparisons with fable-like tales from other geographical regions and cultural traditions.

|

For additional picture books with global settings, see Joy Fleishhacker’s “Reading Around the World.” |

RELATED

Who Will Rule the Trees?

Go Bananas!

The Dark Is For

Spirit Shadow

Turtle Slept In

Planting Hope

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!