Ready, Set, High School: Supporting the Transition to Freshman Year

More preparation for students making the leap to high school is merited, according to middle and high school librarians. Here's how they are helping.

|

SDI Productions/Getty Images |

At Thurgood Marshall Middle School in Antioch, TN, Erika Long could see the gaps. Not the usual gaps researchers talk about, related to test scores or funding. She had worked in a high school library before moving to Thurgood Marshall, and she could tell that her middle schoolers were not going to be ready for what was coming after eighth grade.

The K–12 years are full of major transitions, from the first day of formalized schooling to college orientation. For most of those, educators have turned their focus to “readiness”—the skills students need to be successful at each new stage. Early education experts have developed kinder-readiness guidelines, and most states use some kind of measure to determine college readiness in high school students.

But other transitions are less well studied—specifically, the major jump from middle school to high school. While educator resources such as Edutopia, the Association for Middle Level Education, and even some state education departments offer tips and toolkits to smooth the shift, “high school readiness” has not been widely or formally researched. But more support for students making this change is merited, according to librarians.

“It’s not something we had been talking about or doing previously as a school building,” Long says. It took some time, but her school has started to choose curriculum and projects with high school preparation in mind, particularly those that involve research.

Long and others maintain that high school readiness is vital. Students who are prepared academically and emotionally will be that much further along for the next goal: college readiness. If students have foundational research, study, and social skills in place, they are more equipped to take on advanced coursework and make the most of their high school years.

More intense all around

It’s not so much that classes and social interactions are different in high school, says Len Bryan, library technical systems manager for Denver Public Schools. They just become more intense.

Students have a lot more to manage. In middle school, students adjust to changing classrooms and learning from different teachers throughout the day. In high school, those teachers don’t necessarily coordinate their syllabi with one another, which typically means more homework overall. Opportunities for extracurriculars also increase. While enriching, these can lead to busier, more stressful days for students.

At the same time, Bryan points out, grades matter more in high school, as students think about and apply to college.

In some schools, students can feel that pressure from day one. “Don’t fall into the trap of thinking freshman grades don’t matter,” says Lucy Ibarra Podmore, librarian at Clark High School in San Antonio. Podmore reminds freshmen that from their first day, their GPA is accruing. While they have time to correct early stumbles, that time could also be used to build momentum.

Like most librarians, Podmore welcomes freshmen, orients them to the library, and makes sure they know she’s there to help them learn the language and technology of research.

That proactive welcoming to the library space and resources is key; students will be far more likely to use the high school library if they already feel comfortable with the technology, systems, and tools inside, Long says. All the more reason that research skills like database searches, formatted citations, and annotated bibliographies can and should be mastered in middle school.

|

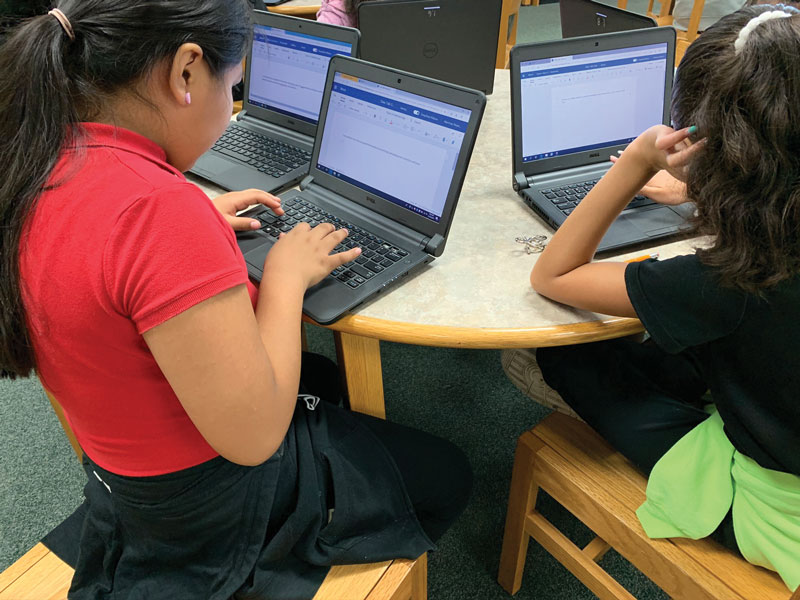

Fifth graders at the Thurgood Marshall Middle School library in Antioch, TN, learn to work in Microsoft Word. |

As her middle school adopted a more project-based learning curriculum that allowed students to choose topics of interest, Long coordinated with teachers to incorporate high school research skills. Because students have dedicated library time in her library, Long focuses on teaching key topics including MLA format, OPAC searches, and online literacy techniques without the pressure of GPAs hanging over them.

This way, Long reasons, when they get to high school, they will be ready to focus on the content of their research. Long helps them set up a research file on their Microsoft OneDrive that can follow them through high school. They could, in theory, have their own collection of research and get deeper into those topics each year.

Middle school librarians have a unique vantage point, says Melissa Thom, librarian at Bristow Middle School in West Hartford, CT. With a “bird’s-eye view” of the school, they can look across subjects to see where connections can be made to strengthen learning in every subject. Thom emphasizes that preparing students for high school requires collaboration across grade levels, as teachers and librarians align research formats and tools, curricula, and the functions of their respective libraries.

With those types of goals in mind, a Kentucky Department of Education toolkit suggests that where campus locations make it possible, students from middle and high school could team up. Clubs and service projects could potentially include students from both middle and high school, easing the social transition. The toolkit suggests a mentoring program wherein a high school student meets with a middle school mentee to help prepare for what to expect. Such programs need oversight, however. A librarian sponsoring such collaboration could provide both the space to meet and the supervision to keep participants safe and accountable.

Those kinds of “vertical conversations” among librarians teaching different middle and high school grade levels “are where we need to start,” says Thom. Middle school libraries can offer helpful activities and instruction, but they have to be tuned into what high schools are doing.

|

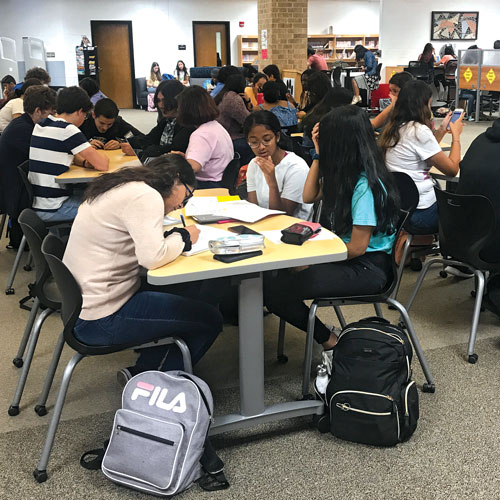

Students study at the Clark High School library in San Antonio, TX. |

Starting over, socially

The social transition to high school can be challenging, Bryan says, by putting many kids back to the sort of “square one” feeling they had entering middle school. Interactions in the library can help: There, things can be more relaxed without the structure of a club or a team, the pressure of a lunchroom, or the agenda of a classroom. Student-to-student or librarian-to-student interactions happen authentically, with students engaging or disengaging whenever they want, and without social or academic penalty.

If the world of high school is too overwhelming, Bryan says, “free, open access to a variety of books and other materials can help students find themselves in literature, in online communities, or even in established high school social circles.”

Podmore sees firsthand that not all kids like the freedom high school offers: It comes with the pressure to socialize, study, and “get involved” in just the right amounts. Any of those things can be terrifying to some teens; luckily, the library can help with all three. Students don’t have to “fit in” like they do in the cafeteria or hallways, they have access to academic help if they need it, and the library can be a hub for extracurricular interests.

When Podmore welcomes freshmen and offers academic advice, she adds a social reminder: They will be exposed to new people and opportunities in high school, and so will the friends they knew in middle school. Sometimes, this means friends grow apart, which can be upsetting and at times painful.

“Don’t struggle in silence,” she tells them. Counselors, teachers, and librarians can connect students to clubs or peers with similar interests. And the library facilitates chance meetings with others who share the same interests.

Importantly, librarians also have book recommendations to help freshmen struggling with the new high school environment. “There’s a whole YA genre that is full of friendship breakups or books featuring YA authors recounting their high school days,” Podmore says.

Lee Daugherty, an English teacher at Glasgow Middle School in Alexandria, VA, recommends a range of young adult fiction to her students as they navigate changing social situations.

Jason Reynolds is wildly popular among her students, as is graphic novelist Raina Telgemeier. A class reading of Reynolds’s Long Way Down prompted an entire unit on the concept of “choices.” Both authors deal with themes like changing friend groups, conflict, and feeling left out.

“That’s in a lot of the literature that middle school students read,” Daugherty says, and some of it never gets old. While Orbiting Jupiter (2015) by Gary D. Schmidt is one of the most popular books among her students, many also love S.E. Hinton’s 1967 The Outsiders, which deals with similar themes of belonging and stigma—both issues they will likely encounter in high school.

“[It’s all] those things that kids want to talk about, but are not often given space to,” Daugherty says.

Middle school librarians can also offer students opportunities and responsibilities that will help foster confidence when they move to high school. By doing things like offering volunteer hours for student assistants or sponsoring clubs, middle school librarians can give students a bridge from the heavily monitored world of elementary school to the more open range of high school, says Bonnye Cavazos, librarian at K–8 Hawthorne Academy in San Antonio.

Sometimes, preparing students means providing them with life skills that will transcend even college. Podmore tries to help her freshmen manage their schedules. If they haven’t used a calendar or planner before, Podmore advises that their first semester is a good time to start. As usual, she reminds them that she, and the library, are there to help.

“There are some great books in the library on time management, goal setting, and more,” she says. With such tips, small and large, librarians help develop not only better students, but more capable adults down the line.

Bekah McNeel is a freelance writer based in San Antonio.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!