Choosing Not To Highlight Dr Seuss Books Is Not Censorship | Opinion

A librarian and intellectual freedom advocate on Dr. Seuss, library policies, and cancel culture.

Many books by well-known and beloved authors are problematic due to racist imagery or stereotypes, as librarians and educators have long been aware. Examples include the “Little House on the Prairie” books, as well as the “Dr. Dolittle,” “Peter Pan,” and “The Indian in the Cupboard” series. Authors may also be problematic due to personal behavior and publicly expressed beliefs—authors such as Roald Dahl, J.K. Rowling and others come to mind.

Recently, Dr. Seuss was in the news after Dr. Seuss Enterprises decided to stop publishing six of his 48 books.

Most school and public Libraries, as well as some academic libraries, own some or all of the six Dr. Seuss books in question. As public institutions, libraries must abide by the First Amendment, and cannot remove books because we disagree with the ideas in those books—that would be censorship. Our school libraries keep books unless they meet board-adopted criteria for deselection (weeding/removal): they are rarely or no longer checked out by library users; are damaged or unappealing in appearance; contain incorrect outdated facts, and so on. Every library has—or should have—a policy and a form that community members may fill out to ask for a book’s removal; for schools, that decision often goes to the school board.

READ: Six Dr. Seuss Titles Deemed “Hurtful and Wrong” Taken Out of Print

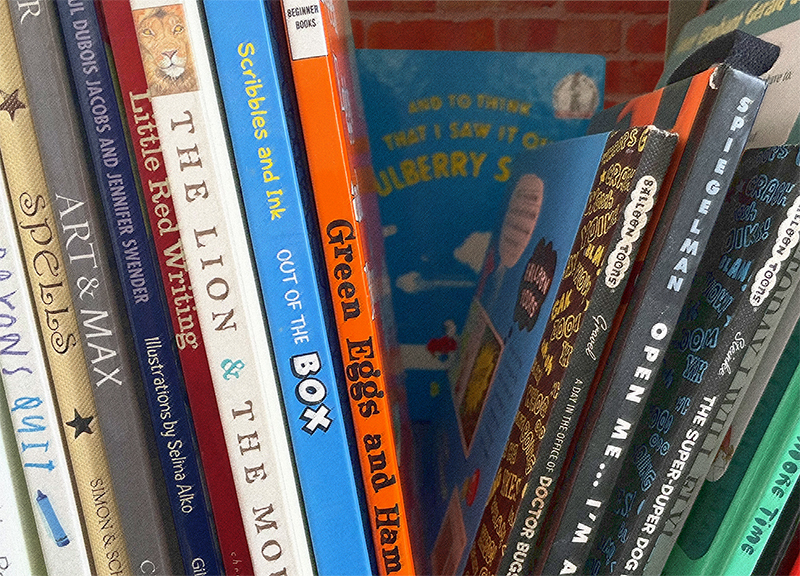

However, while we cannot remove library books, librarians and library staff can and do choose not to promote every book in the library. We choose better, more recent, more diverse, antiracist titles to highlight instead. We can decide not to add the problematic books to book displays, read them aloud to classes, or recommend them to teachers and students. We may also let library users know about racism, stereotypes, or other issues in books, and then suggest different titles as alternatives.

We also often select books other than Dr. Seuss for celebrations of Read Across America Week. This is the approach a school district took this year in Virginia, and it’s a good one. The district did not remove any library books; they simply made better choices for their celebration. As Loudoun County Public Schools said in a statement, "We continue to encourage our young readers to read all types of books that are inclusive, diverse and reflective of our student community, not simply celebrate Dr. Seuss.”

Choosing not to display or highlight problematic titles is not censorship or “cancel culture.” It’s teachers and professional librarians using their judgement to benefit children and families. When we update our curriculum and the novels students read as a class, we also consider these issues. There are millions of books available. Why not skip books with racist illustrations, stereotypes, and other serious problems in favor of books that will be the “windows and mirrors” for all children, as described by Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop?

Many school districts and public libraries have adopted and implemented Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) policies. We have decided that EDI is a priority in our schools and libraries. Those decisions should and do play a role in deciding which books we purchase, highlight, and use in our classrooms and our library programs.

Yes, it’s possible to read a classic novel or picture book with a class or group of children (or with your own child) and point out the racist imagery or other problematic content. However, this does not always happen in practice. In addition, just showing that imagery can do harm. Librarians, teachers, and parents constantly make choices about what to teach and read. Professional judgement calls for knowing and using more current and diverse children’s literature in place of books with harmful content.

Libraries cannot and should not remove books due to content. Library staff can, however, help educate library users. We can use our collection development policies—which describe how and why we buy books—to add amazing new titles. Teachers can pick the best books for their classroom libraries and for their lessons, not books with racist, sexist, homophobic, and otherwise problematic illustrations and text. Public librarians can do the same for their story times and events. We can and must promote, display, and recommend books that provide windows and mirrors for all students and their families.

Miranda Doyle is the intellectual freedom chair for the Oregon Association of School Libraries and one of the district librarians for Lake Oswego (OR) School District. Previously, she was a librarian with San Francisco Public Library.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!