Two Libraries In One: When Schools and Public Libraries Share Space, All Users Benefit

These four carefully planned partnerships resulted in better access to materials and fiscally responsible resource sharing.

|

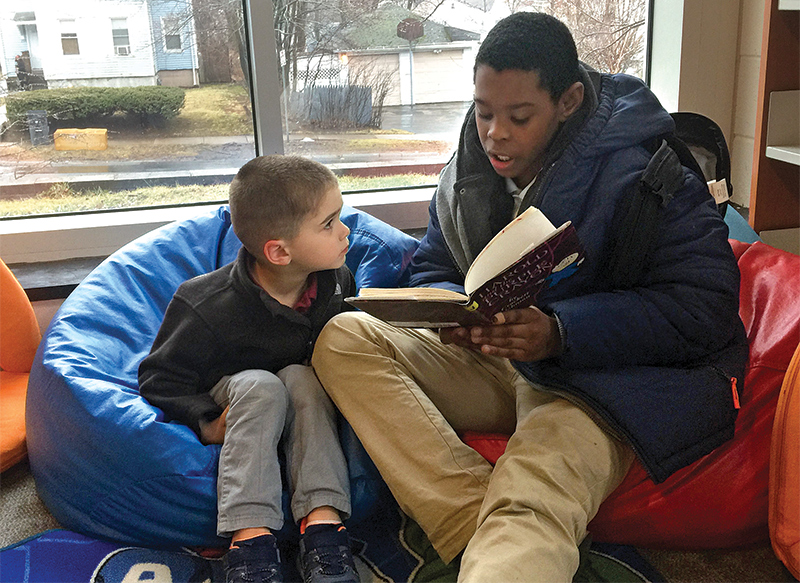

Students at Hartford’s Boundless Library, located at the Rawson School.Photo courtesy of Hartford Public Library |

In 2017, fiscal challenges in Hartford, CT, led to the closure of three Hartford Public Library (HPL) branches. “We knew we would have to work closely with the affected neighborhoods to consider new service models to meet their needs,” says HPL CEO Bridget Quinn-Carey.

One of the closed branches was in Hartford’s Blue Hills neighborhood, home to the K–8 Rawson School, which had a modern, but neglected, media center. Quinn-Carey approached Hartford Public Schools (HPS) superintendent Leslie Torres-Rodriguez to start the conversation about a library colocation partnership to serve the school and the public. With support from a corporate grant, the Boundless Library at Rawson opened in November 2018.

School-public library collaborations take many forms, with both sides committing to increase access and opportunities. Planning and implementing colocated libraries, where one site serves both an educational institution and the public, can be complex. But those who have established joint-use facilities say the shared libraries can greatly benefit both populations. Whether the partners are fully enmeshed in policy and procedure or have some autonomy, the goal is better access and fiscally responsible resource sharing.

In Hartford, a strong partnership was already in place when the Rawson Library opportunity came along. It sprang from the broader Boundless initiative between HPL and HPS, established in 2015. That resource-sharing agreement includes universal school-public library cards, an integrated school-public library system, collaborative programming, and a public library pairing with each district school.

The Rawson Library idea aligned with Torres-Rodriguez’s vision for a “community school,” Quinn-Carey says. “We’re seeing consistent, regular use from the neighborhood, folks coming by to use our computers and attend programs.” The library isn’t yet open on weekends or during the summer, but attendance has risen during the three afternoons it has public hours, from 3 to 6 p.m. The collection primarily reflects the school’s needs, while a small collection of adult materials is accessible during public hours, and HPL users can pick up holds.

First-year grant funds supported the hiring of a school media specialist, who is a full-time HPL librarian with teaching credentials; a library assistant; materials to refresh an outdated school collection; and acquisition of library equipment. General facility costs are covered by HPS. The Hartford Foundation has provided three additional years of financial support, and HPL and HPS are crafting a long-range funding plan.

The value is evident. The school reported an uptick in daily attendance, and “we have already found significant increases in fifth grade reading scores by the end of 2019,” says Quinn-Carey. She attributes the success to open communication and the presence of a media specialist on staff with HPL. “Having an employee who is truly integrated into the school and public library teams is a fundamental underpinning.”

|

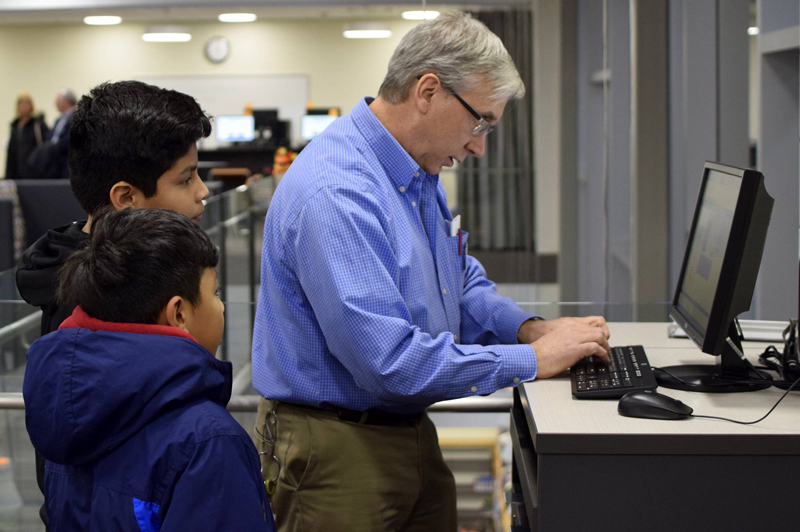

Patrons at the shared high school-public library branch in Kelloggsville, MI.Photo courtesy of Kent District Library, Kelloggsville branch |

Flexibility in Kelloggsville, MI

Many residents who live near the high school in Kelloggsville, MI, have transportation barriers that prevent them from reaching branches of the public Kent District Library (KDL). After a successful bond measure resulted in a new, state-of-the-art media center at Kelloggsville High School, a representative from Kelloggsville Public Schools (KPS) approached KDL about a colocated community library there. “We knew we needed to try and make this work” in the economically disadvantaged area, says Lindsey Dorfman, KDL director of branch services.

“Anyone considering a project like this needs to focus on relationships and come from a place of flexibility,” says Dorfman, who has shifted course as needed. A $150,000 grant to KPS from the Steelcase Foundation jump-started the partnership by funding staffing, programming support, technology, and a collection supplied by KDL. The high school removed its old collection, and KDL provided materials for all ages.

Initially, the books floated—meaning that if another KDL branch patron requested an item and placed it on hold, it wouldn’t come back to the high school library unless returned there. Floating collections are a strategy to fine-tune branch collections to community needs, but in this case, all the popular titles disappeared, and circulation dropped. After the floating collection idea was abandoned, circulation rose.

Public patrons can access all KDL’s electronic resources via eight KDL-networked computer stations. The machines have Children’s Internet Protection Act–compliant filters.

Start-up grant funds provided an initial 20-hour staff person in the library—a KDL librarian who also worked part-time at a different branch. But as money ran out, the school-day hours decreased. Last fall, KDL hired a full-time teen services paraprofessional, Clare O’Tsuji, as lead on the partnership, plus a full-time media specialist.

“The teachers were not especially warm or open to working with [O’Tsuji],” says Dorfman. “There was a fear of possibly losing the partnership.” As O’Tsuji promoted the messaging of “school media center first, public library second,” relations with staff and students warmed.

Like Quinn-Carey, Dorfman says that getting the right person to staff a colocated project is key. “With an actively engaged public librarian to support the media center, we’re seeing 30 to 40 students coming to her after-school drop-in programs.”

Currently, the Kelloggsville branch operates as a public library on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday from 3 to 8 p.m., with regular morning and early afternoon hours in the summer, though KDL may adjust hours to match usage statistics. The popular Saturday family and adult programming, as well as free summer meal service, will be repeated this summer.

|

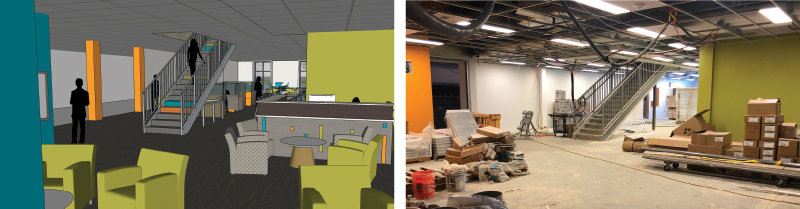

A rendering of a planned shared facility in a Bozeman, MT, high school (right); the facility under construction.Rendering by Cushing Terrell Architects |

A “baby branch” in Bozeman, MT

Gallatin County (MT), home to the city of Bozeman, is the fastest growing county in the state, and the city is the fastest growing of its size in the country. “Our city is exploding,” says Susan Gregory, Bozeman Public Library (BPL) director, “but revenues have not kept up with growth. Our general fund has only increased by one percent or so over the past year.” A new high school is slated to open in fall; when its design was still on the drawing board, the school superintendent at the time, Rob Watson—who was also on the library foundation board—asked if BPL could establish a presence there.

The superintendent was working with faculty at Montana State University to investigate lagging third grade reading levels. “Even in a town that’s as affluent and well educated as ours, there’s still a gap,” says Gregory. “The library is a trusted community organization that can help lay the groundwork for improvement in reading scores.”

The request for partnership with BPL “shows that you should always be building these kinds of relationships,” she adds.

Gallatin High will be located among “miles of new suburban neighborhoods,” Gregory says. The reality of a BPL presence there hinges on final budgeting for the next fiscal year, but Gregory is hopeful. “It’s politically a very popular project, with the school board and city council all very excited.”

The space will be a fully operational school library during the day, and swap over with BPL staff after school. Public services would ideally be staffed from 4 to 8 p.m., Monday through Friday, with four hours on Saturday for early literacy programming. The city budget for BPL would provide staffing during public hours, pending approval. “Our worst-case scenario is to postpone the project for six months,” says Gregory.

The public library will bring in a selection of the “Most Wanted” books, a browsing collection of adult best sellers. The site will also serve as a pickup location, with BPL materials brought over to fulfill holds. The school collection and school-based tech won’t be accessible during public hours, when BPL-provided laptops will operate on the school’s network. The public library ILS will stay separate, too. “The idea is to get a BPL footprint on this side of town with the end goal of opening up a new full-service branch,” says Gregory. “Hopefully this ‘baby branch’ will demonstrate that there’s a need for a library, and we can begin to build support.”

|

Right: Staff at the shared Pungo-Blackwater Library in Virginia Beach, VA; hands-on programming at the library.Photos courtesy of Pungo-Blackwater Library |

Decades of sharing in Virginia Beach

In the spring of 1997, the Virginia Beach Public Library (VBPL) board and staff presented a plan to the city council. It aimed to “improve after-hours access to school libraries and resource sharing between city and school libraries” and proposed renovating and expanding the 1,000-square-foot rural Pungo-Blackwater Library, says Sarah Bell, branch manager.

The city council approved the project, and after discussions, a colocated library at Creeds Elementary School, next to Pungo-Blackwater, seemed the best way to meet the goals. After planning meetings, public conversations, contractual work, and construction, the new Pungo-Blackwater Library opened as an addition to Creeds Elementary in 2000.

While the public library is inside the school, with external public access and an inward-facing entrance, it’s staffed and run as a VBPL branch, says Bell. “The school has its own library media center; the two staffs don’t work in each other’s spaces.” Patron information is kept separate, and the city’s library budget covers the public library needs, while the school maintains ownership of the building itself and provides facility maintenance. Still, the VBPL staff let students check out school library materials after hours and “provides programs above and beyond what the school can do on their own,” Bell says.

Pungo-Blackwater attendance numbers are higher than at the prior location, a community building with a police substation and a parks and recreation office. Evening library hours encourage families picking up their kids to stop in. The arrangement also broadens teachers’ access to materials to support school curriculum, beyond school library offerings.

The future of this long-lasting partnership is bright: Bell is working on “more innovative ways for public library staff to visit the classrooms and provide programming,” she says.

Her next collaboration goal? The school and public library have been working with the Senior Resource Center, located in the old Pungo-Blackwater space, Bell says. That partnership will bring together “three organizations that are bridging all generations.”

April Witteveen is a community librarian at Deschutes (OR) Public Library.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!