Powerful Partnerships: Librarian-teacher collaborations yield robust, original ideas

The strongest partnerships show the depth of librarians’ expertise, enrich curricula, and engage students in deep learning.

|

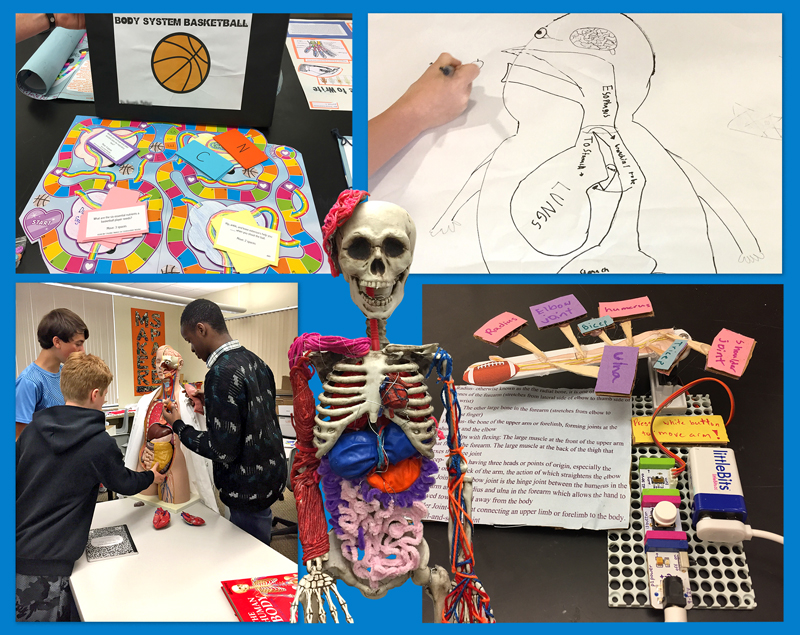

Aspects of Janine Johnson’s human body study (clockwise from top left): a body systems board game; a student drawing; a littleBits-powered throwing arm; a skeleton showing how body systems work together to pat a dog; students collaborating. |

![]() Every day, school media specialists partner with classroom teachers to share a trove of skills, tips, and best practices. The strongest partnerships show the depth of librarians’ expertise, enrich curricula, and engage students in deep learning.

Every day, school media specialists partner with classroom teachers to share a trove of skills, tips, and best practices. The strongest partnerships show the depth of librarians’ expertise, enrich curricula, and engage students in deep learning.

Many of these activities are short-lived, designed to teach one skill or check a box in a particular grade’s standards. But fostering long-term, fruitful collaborations is an essential aspect of school librarianship, library leaders say.

Partnerships solidify librarians’ standing and influence among colleagues and administrators, while also forging valuable alliances among faculty. Students also benefit from the out-of-the-box, original ideas that collaborative thinking can yield.

There’s a reason that multi-week projects with teachers aren’t as common as they should be: Comprehensive, cohesive initiatives can be hard to set up and challenging to sustain. The stakes can feel so high that some may shy away altogether: Carrying out a less-than-successful project could damage relationships with teachers throughout the school and dampen enthusiasm for future collaborations. You have to deliver.

However, it’s vital that school librarians initiate partnerships and see them through, says Ann Carlson Weeks, co-founder of the Lilead Project and professor at the University of Maryland College of Information Studies. Laying the groundwork for successful partnerships happens before planning starts, notes Weeks. While many librarians are afraid of seeming “pushy” in proposing projects, she says, explaining one’s expertise and suggesting how it can help teachers meet academic goals is essential.

It’s key for librarians to cultivate multiple faculty relationships in part because staff turnover can be so frequent, adds Stephanie Ham, a former Lilead Fellow and director of library services for Metro Nashville Public Schools. Being a “proactive collaborator” means suggesting projects while remembering what goals a teacher needs to obtain, Ham says.

A supportive administration helps. “The principal is more responsible for a quality library program than anyone in the building,” Weeks says. “For partnerships to exist and flourish, there has to be support and structure.”

Even if a first effort doesn’t go smoothly, building a trusting relationship can increase the likelihood that a teacher will engage in more.

The complexities of a soccer kick

Librarian Janine Johnson’s collaboration was born from dissatisfaction. Seventh grade science teachers Charlsie Vanderrest and Kelly Hall thought teaching the six body systems (including muscular, skeletal, and circulatory) separately kept the students from understanding how various components worked together. The two teachers at Scotts Ridge Middle School in Ridgefield, CT, came to Johnson and said they wanted to invent a new approach. Looping in assistant librarian Emily Shiller and the district’s tech integrator, Kim Moran, the five started meeting.

Creating a method to track progress and assign tasks to each member quickly became important. The team created a Google site, uploaded the curriculum’s rubric, and marked each member’s progress. They wanted the project to meet the upcoming Next Generation Science Standards as well as carry a technology and research component.

The group built a semester-long project that challenged students to show in a multimodal format how the various body systems coordinated to complete simple everyday acts, such as kicking a soccer ball or playing the piano.

Students started with research, using virtual reality, websites with 3-D images, and printed materials to learn about the human body. Along the way, they learned how to search databases, use advanced filters, and construct proper citations. As they started to create their projects, students had the option of making videos using WeVideo, building a mock Wikipedia entry, or creating a 360-degree model of human body.

They went “from learning about to figuring out,” Johnson says.

The groundwork for this successful partnership, which won the American Library Association’s 2018 Collaborative School Library Award, started well before planning began, Johnson says. The principal of this 500-student school, Timothy Salem, encourages his staff to take risks, in part by turning school meetings into time where staff can explain new resources and tools, sparking potential collaborations.

One of Johnson’s challenges is “keeping up with the curriculum, because it’s always changing,” she says. While she consults with teachers to learn about their needs, she also updates them frequently on new items added to the school’s growing maker lab, such as a green screen students can use for film projects or a classroom set of Google Cardboard viewers.

|

A Parker School student tests an invented art machine; teachers and school librarian Mary Catherine Coleman (second from left) brainstorm. |

Artful inventions for the youngest students

One concern in putting together multi-week projects is making sure that the pacing works for students. Too slow, and you risk boredom and the bad behavior that invites. Too fast, and some students fall behind. Johnson and her teachers set many mini-deadlines within the project, knowing if students had too much time, the work would expand to fill the space.

That challenge was front-of-mind for Parker School librarian Mary Catherine Coleman. While the private pre-K–12 Chicago school prides itself on experiential learning, leaning on the teachings of John Dewey, Coleman knew that a seven-week project with first graders might not work. “It’s a bit of a risk. The concern with younger kids is their attention span,” she says.

Coleman, the school’s three first grade teachers, and the education tech specialist decided to create a project around Peter H. Reynolds’s acclaimed book The Dot, which details the journey of a girl, Vashti, who slowly discovers her artistic ambitions and learns how to help others reach their potential. “On the surface, the story seems simple,” says Coleman, but it carries a deep message.

Coleman used a half-day meeting with her team to map out how to bridge the book’s lesson into a project where six-year-olds could learn what it means to make their mark on their community.

The students met in groups and explored how they could collaborate with others, creating words that helped show the benefits of working together. The project culminates when students build a simple machine that can create a painting.

This building challenge is emblematic of how projects can improve as they are repeated. Coleman says in the first year students connected a motor with a fan to a plastic cup outfitted with a magic marker. While the results were fine, there wasn’t a lot of variety. The next year, they used a machine that featured squirt bottles of paint. “That was really messy,” Coleman says with a laugh. “The art ended up being really cool, but there was still a limit to what they could build.”

This year, Coleman and her team didn’t show kids those previous inventions and allowed them to use a wide range of materials in the library makerspace, from cardboard to circuits. “There was a lot more trial and error,” she says, which involved building, testing, and revamping their work to overcome perceived deficiencies. “There was a lot more student design in this version. We didn’t end up with 30 of the same project.”

This new approach added two weeks to the project timeline. But the project’s past success prompted teacher and librarian to take more of a risk.

It’s a reminder not to let limitations cap what your children can accomplish. Consider the case of Tatanisha Love, library media specialist at Loch Raven Technical Academy in Towson, MD. When Love strategized how to teach students about bullying, she knew she wanted to do something different. The idea of having students create a mural was appealing, because they would learn about different types of harassment and then figure out how to depict them in art. There was only one problem: Love didn’t know very much about drawing.

For this 10-week project, Love partnered with a muralist who taught the middle school students about shape, form, and shade. Reaching out to an expert is exactly what librarians are good at doing, she says.

The freedom from having to run every part of the program helped Love consider the bigger goals that she had in mind when she started. “I didn’t micromanage everything, which I tend to do,” she says. Love now uses the four-panel mural to help teach anti-bullying lessons.

Broaden your students’ perspectives

Michelle Carton, district elementary librarian in Anchorage, AK, didn’t let geographical location stop her from forming far-flung partnerships. Using social media and paying strict attention to time zones, Carton, also SLJ’s 2018 Champion of Civic Engagement, has launched a variety of projects with other schools, including those in Central and South America. Giving young students firsthand access to peers around the world helps build understanding of different cultures, she says. Through these partnerships, students understand a variety of issues, from how Halloween is celebrated in Mexico to the ways that families cope with trauma in the case of natural disasters, such as the California wildfires.

The trauma information was relevant when a 7.0 earthquake hit Alaska on November 30, 2018, she says. Their understanding of the impact of trauma helped them process their own.

The librarian also aims to give students key information on a hot topic, such as the Alaskan debate between pro-salmon forces and those who want to open the state’s Pebble Mine to exploration for copper and gold. Having students understand issues and make up their own mind while still in elementary school is excellent preparation for the higher thinking skills they will need in middle school, Carton says.

|

Tatanisha Love (left) and fellow Baltimore County media specialists Kenneth Bouchat and Donna Anderson; an anti-bullying mural by Love’s students. |

Starting from scratch

For many librarians, projects come together through familiarity, both knowing how teachers like to work and what material they need to cover.

Coleman has learned that going to a teacher and saying you have an idea for a project can end up sounding like one more thing they have to do. “They have to be part of the process,” she says. “If the outcome doesn’t help them advance, it’s a hard sell.”

“In a lot of cases, [librarians] wait to be asked, rather than ask for a place at the table,” Weeks adds. “It’s important to be aggressively helpful.”

“We’re past the point where we wait for people to come to us,” says Nashville’s Ham.

When Shawn Joseph took the helm as Nashville’s school superintendent in the fall of 2016, he brought with him a strong imperative to boost reading instruction and scores. Ham saw an opportunity. She leaned on her existing relationships with teachers to create new projects to help them meet their reading goals. “I’m willing to make whatever they are teaching a priority,” she says.

|

One of Johnson’s students works on a project on border conflicts, a collaboration with a social studies teacher. |

Learning from “Brotherhood"

For Stephanie C. Stargardt in Chester, VA, the “perfect storm” of collaboration began a different way. When a new teacher started at Carver Middle School and was tasked with teaching both social studies and English, the librarian had an idea. The novel Brotherhood by A.B. Westrick had just been published. The historical novel deals with the relationship between a white teenager and a black teenager right after the end of the Civil War. Because the story is set only about 20 minutes from Carver, Stargardt knew the familiar landmarks would heighten student interest.

The librarian was fortunate to have the author help out in numerous ways, including recording herself reading sections about physical locations in Virginia so that when students visited, they could hear the author’s narration through a QR code.

One of the most moving stops was an African burial ground, Stargardt says. Although described as a swampy area in the book, it is now a manicured open space sitting right next to I-95. As the 13-year-olds read the area’s markers and plaques, “you could have heard a pin drop,” she says. “They were completely engrossed.”

Stargardt and the teacher used the book’s theme to delve into how some groups of people get involved in activities such as the Hitler Youth or the KKK without fully understanding what these groups are about. The school’s resource officer came in to talk to students about gangs in the area. The six-week project not only tied students into their area’s past, but also helped them understand the history of racism that, a year later, resurfaced in the white supremacy march in nearby Charlottesville.

“I don’t feel like the kids thought they were doing work,” Stargardt says. “They were explorers, they were really studying something.”

While the project helped guide the new teacher through the curriculum, the librarian says, with the school constantly mindful of accreditation, it has become harder to set aside so much time for a single project, especially with teachers in only one subject. “Teachers hold onto their time very tightly,” she adds.

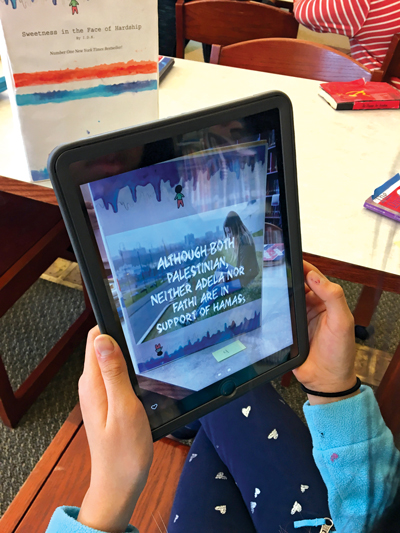

Back in Johnson’s Ridgefield library on a recent afternoon, students were hard at work on their latest project, learning about border conflicts around the globe. In this collaboration with social studies teacher Jessica Burns, students research various regions such as India/Pakistan and Israel/Palestine through Newsela stories. Then they write the final chapter of an imagined book that resolves the conflicts. Finally, they create covers that would “sell” their fictional book and create a 30-second promotional video.

At the library, choruses of “How do you do this?” filled the air as students helped one another and Johnson and Burns offered light advice. Kids worked in groups, bopping their heads while evaluating royalty-free music for their soundtracks and playing their video for their friends. Shouts of “Check this out!” were cut short as creators inevitably spotted flaws they needed to fix.

The project’s wow factor is HP Reveal, an augmented reality platform. “The kids see it and their eyes light up,” Johnson says. “But they say, ‘I can do that.’ The students see how we like geeking out with technology and they get all fired up about what they are doing.”

When the principal stopped in, reaffirming approval of the exercise, the students barely noticed. Johnson and Burns hovered around the edges, watching the kids absorbed in their work.

Wayne D’Orio is a freelance journalist who writes frequently about education, equity, and rural issues.

Wayne D’Orio is a freelance journalist who writes frequently about education, equity, and rural issues.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!