Youth, Interrupted: Author Deborah Ellis and Youth First President & CEO Liz Ryan in Conversation

My Story Starts Here author and activist Deborah Ellis talks with Youth First President & CEO Liz Ryan about how our society treats youth crime and the faults of the criminal justice system.

In both the U.S. and Canada, systemic problems like poverty, racism, substance abuse, and inadequate child welfare systems contribute to youth crime and incarceration.

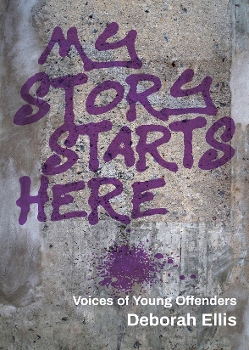

Two individuals who are working to reframe how our society treats youth crime are Deborah Ellis and Liz Ryan. Ellis is a Canadian activist and award-winning author of many books for young people, including her newly published collection My Story Starts Here: Voices of Young Offenders (Groundwood, Oct. 2019; Gr 7 Up). Ryan is the President & CEO of Youth First Initiative, a U.S.-based nonprofit which seeks to dismantle the youth prison system and offer youth-led alternative initiatives. The two discuss why our criminal justice systems in both the U.S. and Canada are so broken, how young people end up entangled in those systems, and what we can do to empower youth to find a sustainable path towards a more just future.

Mallory Weber: How does the school-to-prison pipeline system contribute to youth incarceration, namely racial disparities? How can the school-to-prison pipeline system be dismantled?

Deborah Ellis: In Canada, racism plays a big role in that most of the disproportionately large part of the incarcerated population is First Nations. When people get released from prison and they're on conditions, they get seen more quickly as people who might commit crimes, therefore they get picked up again and again. I think that's one of the things that lead to disproportionate numbers of people of color being in the prison systems in Canada.

Liz Ryan: Yeah, it's very similar in the U.S. unfortunately, where the vast majority of youth who are locked up are young people of color and it's not because they commit more crime, it's because the system treats young people of color much more harshly and much more punitively even when they commit the same crimes and offenses that white youth commit. Our system is just much more harsh and much more punitive on youth of color. And that really stems, I think, from a long legacy of slavery…in America.

DE: [There are] similar kinds of histories in Canada with regard to the First Nations people. In Canada, when kids get released there's usually a lot of conditions. Is it the same thing in the States? Bail conditions, that kind of thing?

LR: It varies from state to state because we don't have one national system; it's different systems in each state. But for the most part, every state has some type of juvenile court that handles these kinds of cases and then depending on which ages, and in the state that is providing juvenile services or youth services, they handle the cases in a variety of ways. But one of the things we know here is that kids are kept on probation for long periods of time, way too long, with too many conditions, and conditions that frankly set them up to fail…So when we look at the data in the U.S., and I imagine it's similar in Canada based on what you said, potentially a quarter of kids who are locked up are locked up for probation violations. [There are] probation violations like not showing up on time, not meeting one or more of the requirements of their probation terms; so it doesn't mean that they've committed another offense.

DE: When people live in poverty they have a very tiny margin of error. If they can't make the bus fare that sets off a whole chain of events where that could land them back in prison. A lot of kids I talked to had difficulty with meeting the conditions and they kept getting in more and more trouble because of that.

LR: In your book, I think the stories are really rich and varied. There were some central themes in there—that kids end up in the justice system through a variety of ways, right? Through the child welfare system, through the mental health system, through the education system, [and] some being homeless. The justice system is kind of the last open door, and unfortunately ensnares too many children who should have been served in the community and in other programs. When I was reading the stories, I was like wow, these are so similar to what I hear from young people in the U.S.

DE: I guess it kind of cuts through cultures, doesn't it? And nations. In Canada, a lot of the kids were talking about [how] they'd be in foster care and go from home to home to home. And then something that they would do in foster care, that if they did it in their own family, would be chalked up to just kind of a bad day. But in foster care, they can be charged with a crime, for like, kicking the door or something like that. And then that just sets off where they go from there. Do you find similar things in the states?

LR: Yeah, very similar. There are incentives really for the child welfare system to wash their hands of kids in foster care. I think one of the themes in your book really is the separation of children from their families. I know the U.S. is talking about that right now in terms of the immigration system and what's happening around immigration, children being separated from families, but this has been happening for hundreds of years in the justice system. And in the child welfare system as well.

DE: The kids who are going through that trauma now, they're going to carry that trauma with them for—could be for the rest of their lives if they don't get help in dealing with it. One of the kids in the book talks about how soldiers come back from Afghanistan, or the Middle East or someplace, and they have PTSD from the terrible things that they went through. And she thinks that children should be able to claim that they also had PTSD from the things that they've been through in the foster care system or the justice system, or just with parents who are unable to care for them. I thought that was pretty wise.

LR: I don't know if this is true in Canada but I know in the U.S. that a lot of the research shows that most teenagers engage in some type of delinquent behavior during their teenage years. And most kids age out of it, so that engaging in delinquent behavior is normal adolescent behavior, [and] it's not necessarily the fault of the parent...When you look at all the programs that are most effective, at least the ones that have been studied here, it shows that they're all ones that draw on the family strengths and assets. They're all family-focused, family-based programs. So we know kids thrive best in families, but what our system is doing is actually separating children from families and breaking those contacts, putting kids in faraway places.

DE: In terms of this interview, that would be a really good answer to that question of how can the pipeline dismantled. It would be to provide more support for struggling families to keep those folks together so that they can support each other and get past this difficult time. Would that make sense to you?

LR: I do think that would make sense to me. What I hear from family members is that when they needed help they weren't able to access resources and support. Their kid had to get into the justice system before they could get services and support. We should make this available to families long before there are signs of a young person needing support. But on the other hand, I also think that some of the stories were just so powerful. Kids engaging in survival crime, selling drugs to bring in money for the family that's living in poverty, or kids who are bored; there's not enough activities or opportunities for them.

DE: It's certainly cheaper, isn't it, to do that upfront than to have to spend all the money to incarcerate somebody…In Canada, we don't seem to have a lot of organizations to work with families of incarcerated youth. I mean, there's the social support, social services, and that kind of thing. But a lot of the families that I talked to…they feel very isolated actually when their child gets involved in criminal activity. They feel like they can't reach out to anybody because of that. So they feel very alone. Is that something that you've heard?

LR: Yeah…this system, the justice system in the States provides almost nothing for families. In fact, the message that they send to families is: "We don't want you, we don't need you.” They, children, are removed from the home, their parents can have very little contact with them. It's very prescribed—the amount of contact. Limited phone calls, limited visits, things like that. One of the things that have really emerged in the last 15, 20 years are family-led organizations that work with families and support families, groups like Justice for Families which is a national nonprofit organization that works with families all over the country whose kids are justice-involved. We partner with Justice for Families because of their grounding in what families want and need to help their young people.

DE: I think that's a wonderful thing. It makes people recognize that they have some power in the situation and that they don't just have to take the status quo, that they can work together to make things better.

MW: I think you both touched on this but what role does mental health, especially mental health awareness, play in the trajectory of kids who end up incarcerated or navigating within the criminal justice system?

LR: I think this may be different in the U.S. than it is in Canada because we don't have universal healthcare. We have a very broken, fractured healthcare system. Kids who need mental health services don't get those in the community and unfortunately, they often get shoved into the justice system. So there are kids who are trying to access mental health services getting detained in juvenile detention centers even if they haven't been charged with anything. They can be there for months at a time. And then they're institutionalized rather than being served in the community, which we know is so much better. And…because our health system doesn't function properly, then we're not serving the kids…we're just serving them in another system, in a system that is punitive by nature. And when kids end up in that system, it doesn't necessarily mean they're going to get mental health services or appropriate support…I don't know if it's the same for you at all?

DE: In Canada, we do have a different kind of healthcare system than you have. But we still have kids who have limited ways of expressing the pain that they have, and if they don't feel comfortable talking to an authority figure and they have no other outlet for it, it's going to emerge in some kind of way that is contrary, against the law. And rather than trying to see the whole picture of the kid, the focus becomes on that particular action. Then, of course, that leads them into the system. If we had a more overall picture of what someone is going through, we might be able to help them out and keep a lot of other things from going on. I think they're absolutely linked, no matter what kind of healthcare system you have. Do you guys do restorative justice down there?

LR: Very, very limited amounts of it. It's only now that it's starting to get more traction. And it actually started more in the schools because we also had a situation [in the] last 25 years or so where law enforcement has been placed in schools. We have young people organizing and pushing back on that and saying no. If there's a situation in school that requires attention, perhaps that would be better handled through a restorative justice model in school, rather than suspending kids. We're starting to see that take hold in schools and I'm hopeful that the justice system will do that more. But unfortunately, it's just a handful of examples. And we can learn a lot from you all and others who are engaged in more of it [restorative justice] than we are.

DE: It's starting to get some more traction in Canada and there are local community counsels that meet and deal with the young person who's been in trouble with the law. [They] come up jointly together with a solution of what this person can do to kind of restore things. One of the things I like about it is that when we do something wrong and if we think that we've gotten away with it…we still carry it with us in our psyche. Once we admit that we've done something wrong and fix it, it just goes away and we don't have that burden anymore. For young people to be able to do that, and admit that they screwed up, fix the problem, and then just go on with their lives, I think that could be a really lighten-their-load kind of a thing, you know?

LR: Yeah. And also…it's not like the current system actually heals anyone or restores anything, right? It's a system that doesn't work for anyone, whether you've been a victim of a crime or a survivor of a crime or you've been engaged in delinquent or criminal behavior. We know that we have to be doing something different. This woman named Danielle Sered has written a book called Until We Reckon which really talks about the need for healing and…if victims want the young person who's engaged in behavior that's been harmful to be held accountable, then there's a way to hold someone accountable and to heal the community but also the person who was engaged in the behavior. We're hopeful that there will be much more of this kind of pioneering work around the country. I think you all in Canada have led the way on this, as well as others in the rest of the world.

DE: My understanding of it is that it's an outgrowth of traditional First Nations practices. One of the recurring themes I found when I was doing this book is the very low expectations that kids have for themselves and their lives. And for the adults around them. They just didn't think that anything good was ever going to happen to them. I thought that was very tragic because since they can't expect anything, then they can't feel like they can hope for it or work toward it. I'm wondering what your thoughts are on that Liz, how do we make it so they have things that they can reach for and belief that they can get there?

LR: I think we have to provide kids with the basic supports that they need to grow and thrive. You see...like in the stories you have, where kids are on child welfare and they end up in the justice system, or the young person's homeless. When a young person is homeless or a young person is ending up in a child welfare system, they've been failed by the adults around them. If we want kids to have higher expectations, we actually have to meet those expectations ourselves as adults. We have to stop looking at kids as the problem and what we have to do to fix the kids, and we have to look at the system that we're upholding. So even if that means the program has to be completely redesigned, and it's not as convenient for the adults but that it's actually something [that] supports young people effectively. That's kind of what I feel we need to do, and even having things like a basic children's bill of rights.

DE: Why do you think that is? Why do you think your country hasn't done that?

LR: I think there's a lack of political will. I think there's a lot of lip service paid to children but because children don't vote they don't have any power. So you have a situation where our political system is heavily influenced by people with money, people with power, and children don't have either. So it's something that's gonna take some real muscle. But also it's going to take politicians not worrying about what's going to happen in the next election and doing the right thing by kids.

MW: What can individuals outside the framework of the system do to help bring more healing to victims and perpetrators of youth crime?

DE: I think one of the things we can do is…open our minds and recognize that any family can be touched by this, any one of us can be touched by this, and that it's not just somebody else's problem, it's something that the whole community could be involved in. And by wanting our tax dollars to go toward things like community centers and community programs and proper funding for child welfare programs.

LR: In the U.S. we have organizations that are focused on trying to transform the justice system, where we're trying to get the resources out of incarceration, putting more resources into programs that help young people grow and thrive. There are campaigns that people can join in the U.S., or start their own campaign. On our website, nokidsinprison.org, you can find a whole variety of tools and resources to be able to join a campaign in your area, and if there isn't one, to start your own campaign...I would encourage people to reach out to others in their community because there are young people who have been impacted by this system who have tremendous expertise and who, in many cases, are willing to share that expertise. Like in the stories that you read in this book, I think you'll see these young people, they know this system. And they know what the problems are and they know what the solutions are, and…those are things that we can be supporting.

DE: Yeah, and everything that we do to build our communities, whether it's community dinners or food banks or clothing drives or anything like that...and having that helping hand or the clean pair of socks, you know, it can make a huge difference in a kid’s life. A lot of the kids talked about how it just took one individual saying nice things to them every now and again to make them rethink how they felt about themselves. Even if we don't know whether or not that person we're talking to that day has had a rough time…we never know what the outcome of that is going to be. It doesn't necessarily have to take a lot.

LR: Those are really great points, meeting those basic needs and doing what you can to support young people is really a great place to start.

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

|

|

Deborah Ellis |

Deborah Ellis has more than thirty books to her credit. She has won the Governor General’s Literary Award, the Ruth Schwartz Award, the Middle East Book Award, Sweden’s Peter Pan Prize, the Jane Addams Children’s Book Award, and the Vicky Metcalf Award for a Body of Work. She has received the Ontario Library Association’s President’s Award for Exceptional Achievement, and she has been named to the Order of Canada. My Story Starts Here: Voices of Young Offenders was published on Oct. 1, 2019, by Groundwood Books.

|

| Liz Ryan |

Liz Ryan, a campaign strategist, youth justice policy expert, civil and human rights advocate and fundraiser on issues impacting children, youth and their families, is President & CEO of Youth First Initiative. She is responsible for the organization's overall strategy, management, and resource development. Previously, she founded the Campaign for Youth Justice (CFYJ), a nationally recognized non-profit and since CFYJ was launched, more than half the states have reduced the prosecution of youth in adult court. Liz has worked at several national non-profits, including the Center on Budget & Policy Priorities, the Youth Law Center, and the Children’s Defense Fund, as well as holding senior legislative and policy positions on Capitol Hill. Liz holds a Master's Degree from George Washington University and received her B.A. from Dickinson College.

Mallory Weber is a school librarian at Convent of the Sacred Heart in New York City and is a nonfiction reviewer for School Library Journal. She is a Smith College graduate and is currently attending a Master's program at CUNY Queens College. To read her review of My Story Starts Here, click here.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!