Librarians Offer Personal Attention and Community to Students Facing Challenges

These librarians provide books and a sense of belonging to marginalized students and those academically behind, living in poverty, or facing other difficulties.

|

Janet Damon’s Black to Nature program combines books with the outdoors.Photo courtesy of Janet Damon |

At Mount Vernon Middle School in Raleigh, NC, librarian Julie Stivers often encounters students with negative feelings about reading.

“Students come to us with reading trauma because of never seeing themselves represented in books or being shamed for the type of reading that they like to do, whether that’s graphic novels and manga or reading ‘Wimpy Kid’ over and over again,” says Stivers.

For the past six years, she’s worked at an alternative school, technically an academic recovery school, a place for students who have struggled to keep up with their work on other campuses.

Stivers says that for “some students, being in a 30-student-per-classroom environment just does not work for them.” She adds, “We have a 10-to-1 student-teacher ratio, so students just get a lot more one-on-one attention.”

It can be difficult for librarians working in schools where students face special challenges. Students who are behind academically, who are living in poverty, who have unstable family lives, or who are marginalized because of their race, ethnicity, or identity may need the school library more than anyone. However, the libraries that serve these students may not have the funding for the necessary resources. That’s where individual librarians can make a difference and help bridge the gap with personal attention and a focus on community.

“I think students come here, and they’re able to rewrite their own stories,” says Stivers. “It’s not like we’re saving them.”

She says a lot of her students have never had a positive experience in a library before coming to her school. Some have memories of picking up a book only to be told they would never be able to read it or being directed to books in Spanish based on their appearance when they don’t speak or read the language.

Often her students simply say they don’t read. She’s heard this so many times and seen so much defensiveness about reading that she doesn’t flinch in these situations.

“As soon as they see that I’m not going to force them to read, that goes away really quickly,” says Stivers. “Then I just try to get them to talk about anything.”

It starts with making the school library a welcoming space, which is a big part of her efforts to heal students’ reading trauma.

“I build community by building a space where students see themselves and where their whole selves are welcome, and then I nurture their interests relentlessly,” says Stivers, who has students fill out a survey she calls “interests and fandoms” to tell her more about what they enjoy.

Stivers makes a point to search for books based on her students’ responses. She oversees two clubs that celebrate anime.

Kevin Valdez-Ocampos attended Mount Vernon Middle as a seventh grader. He graduated from high school this year and still keeps in touch with Stivers.

“I remember how she was the first person that actually listened to me while I talked about anime,” says Valdez-Ocampos. “That was a big, big, big deal to me at the time. She was like a second mother to me.”

When all of Stivers’s students were remote, she drove around delivering books to her kids who wouldn’t otherwise have them. She also held one-on-one online conferences with each child to learn more about them and the types of books they might like, a feat made simpler because her school has only about 100 students.

Stivers calls these conversations magical and says they can lead to making a connection that helps a reluctant reader find just the right book. She recalls handing a student Tupac Shakur’s The Rose That Grew from Concrete. The volume of poetry by the slain rapper and actor is one of the most popular books in her library.

“When I handed it to the student, she smiled so big,” says Stivers. “She covered her face because she was nervous about smiling, and so I asked her, ‘Did you ever think you were gonna smile that big in a library?’”

Stivers says the student laughed and said no. “That probably took two months for [her] to smile so big, but it felt like such a victory.”

|

Janet Damon’s program nurtures a relationship with nature and books in Denver.Photo courtesy of Janet Damon |

Nature’s healing power

For Janet Damon, a win for her students in Denver Public Schools means they feel like they belong. Segregation remains a big problem in the district. An analysis by the Denver Post found that during the 2018–19 school year, more than half of the city’s schools were just as segregated as they were in the late 1960s.

Last summer, after the murder of George Floyd and the national reckoning with systemic racism that followed, Damon, the district’s library services specialist, created the Black to Nature Book Club.

Although the club is part of a special outreach to Black families, it’s open to all. Damon says the group has attracted Latinx and Indigenous families along with blended families raising Black or biracial children.

The group hosts socially distanced outdoor activities such as hikes, kayaking, canoeing, zip-lining, fishing, and archery.

“We kind of tied it back to the research that has been done to show that when we’re in green spaces, when we’re in nature, it reduces our cortisol,” says Damon. “It helps to reduce our blood pressure.”

Being outside, she says, is “in and of itself a healing experience.”

Damon says those outdoor experiences were especially welcome last year when the country erupted in protests over the killings of Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and others.

“With all of the stress and all of the things that were happening, especially last summer, we just felt like it was critically important that families had a space where they could go to see one another, to be safe outside, and to reconnect with nature as both a cultural practice that’s grounded in the relationships with nature that ancestrally people have, but also to see the relationship to land that has been a grounding for our community for a long time,” says Damon.

During these outings, there is also a read-aloud, and students get to pick a book to take home. Most of the books are about nature. Some of the events include presentations by experts on topics such as Colorado native species and beekeeping.

Ronda Haynes-Belen and her two kids started participating in the club last summer.

“It was nice to get out of the house and go someplace,” says Haynes-Belen, who adds that meeting other Black people who were excited about nature was a bonus.

“I don’t meet many people that are also interested in those same things,” says Haynes-Belen. “As a single parent, it’s nice to be able to bring your children along for those kinds of experiences. There’s some other programs, but they’re adult only.”

Osharron Awatt has been bringing her kids to the outings from the very beginning. She says her favorite part is “all of the wonderful brown children that my children get to be around.”

Denver is just under 70 percent white, and some Black children attend schools with few kids who look like them.

Awatt says engaging in kayaking and archery breaks stereotypes about “what most people think that we should limit ourselves to.” She adds, “We enjoy the outdoors just as much as anyone else.”

Helping children feel good about their culture and building relationships are a big part of Elizabeth Beamer’s work at Cherokee (NC) Middle School.

The majority of her students are members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Their school is located in the Qualla Boundary, land purchased by the tribe from the U.S. government in the late 19th century that is now held in a federal protective trust.

Like so many communities around the country in recent years, the area surrounding the school has experienced the devastating effects of drug addiction. The children of those struggling with drug problems suffer a lot. In some cases, they’re growing up without parents.

“They may have passed away,” says Beamer. “They may be incarcerated. Some of our kids are being raised by grandparents, and sometimes that can make it challenging for the students, because they have a lot of emotional trauma. Then, on top of that, to come to school and participate can be kind of hard sometimes.”

And no matter their home life, the students still carry with them the pain of past injustices committed against Indigenous people.

Beamer says she’s educated herself about the trauma Native Americans experienced through the forced removal from their land and abusive treatment at boarding schools that punished children for speaking their tribal languages and maintaining other aspects of their culture.

“It’s important to be aware of it because even though it’s not happening now, they still carry that with them,” says Beamer. “That history is very much a part of who they are as a people. We want them to feel safe at school. Nobody wants those experiences that happened to happen to our kids. The school system has worked very hard to make sure that teachers coming in know the history and how we can relate better to the students.”

Beamer also makes sure that the library reflects the students’ heritage. There is a large section of books by and about the Cherokee people and other Indigenous groups.

Beamer says she works hard to learn the names of all 300 of the students at her school. A large part of her job is building connections with them and making sure they feel welcome.

“I try to make the media center a place where they can just come and read and relax and just have a little bit of space or a breather,” says Beamer. “Some kids just come in here and talk to me, and I don’t really say anything. I just listen to what they have to say. They need that, and they don’t always get that.”

Beamer has been the media specialist at Cherokee Middle since 2008.

“The kids really like that I’ve been here for a long time,” says Beamer. “Knowing that I’m going to be here and I’ve been here for a while seems to reassure them, probably because they don’t have that stability all the time in their lives.”

|

Ingrid Hanson strives to create a space where students feel safe and welcome, and find titles they like.Photo courtesy of Ingrid Hanson |

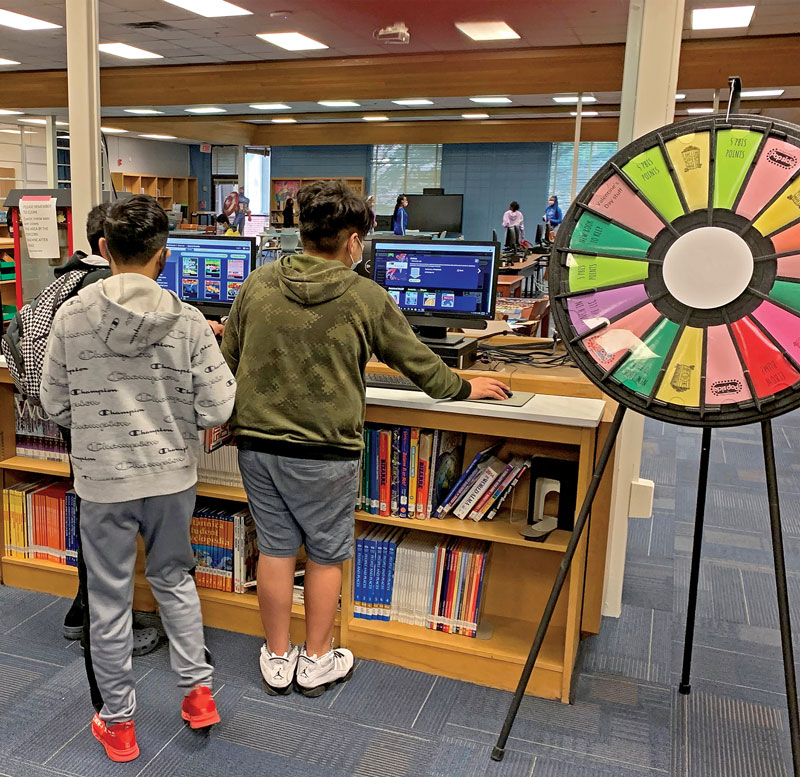

Creating stability for transient students

Students at Lindley Sixth Grade Academy in Mableton, GA, are also looking for stability.

“We have a transient population,” says Ingrid Hanson, the school’s library media specialist.

She says it’s not uncommon for kids to start the year at Lindley, move away and attend another school, and then return to Lindley to finish the year. Most of the children are living in poverty, with 85 percent receiving free or reduced-price lunch. More than 70 percent are Black or Latinx, and many are learning English.

This year Hanson’s students met virtually for an enrichment book club. Kids close to moving from basic to proficient in their reading scores were chosen to participate, and it became a real hit.

“I was out on spring break in the grocery store, and my phone went off,” says Hanson. “It said somebody had started my [Microsoft] Team’s meeting, and there were 10 kids in the waiting room.”

Hanson had to tell the students there were no book club meetings during spring break. She says they missed having fun with their friends during remote learning.

“They were showing up virtually for classes, and then they were leaving,” says Hanson. “There wasn’t necessarily that time to just hang out and talk. I think they were just really looking for that personal contact, not only with me, but with other kids.”

To make sure her students keep reading this summer, Hanson will be doing read-alouds online. She hopes hearing the first chapter of various books will pique rising sixth graders’ interest in finishing them. After each read-aloud, she will be going to the large feeder schools and handing out copies of the book she just read from to any student who wants one. She also told her students who would be leaving the school that there would be books for them as well.

“I make sure that the books I’m offering are all of the titles that I can’t keep on the shelves and that are checked out frequently,” says Hanson. She also works closely with classroom teachers to figure out which books would appeal to her students and to encourage them to read.

She says it boils down to kids being receptive to people who show they care.

“As so many other people have said, kids don’t learn from people they don’t like, and kids aren’t going to check out books from people they don’t like,” says Hanson. “One of the reasons my programs have been so successful is because we’re inviting. They walk in, and that is a safe place where they are loved and welcomed and seen and heard.”

Marva Hinton is a freelance journalist, a contributing editor at Edutopia, and host of the ReadMore podcast.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!