Jarod Roselló on the Magic Behind his 'Red Panda and Moon Bear' Sequel

The graphic novelist strives to emulate kids’ storytelling styles in his books, about Cuban American siblings who use a little magic to fight monsters.

When he’s not creating comics, Jarod Roselló is an assistant professor of creative writing at South Florida State University, and he also runs storytelling and comics-making workshops for children.

When he’s not creating comics, Jarod Roselló is an assistant professor of creative writing at South Florida State University, and he also runs storytelling and comics-making workshops for children.

“One of the things I noticed when I was making comics with kids was that they could just throw in an element that had absolutely no grounding within the reality of the world they had set up,” he says. “It wasn’t a problem for them, it was just an opportunity to imagine what could come next.”

Adults, on the other hand, tend to stick to cause-and-effect logic when constructing stories.

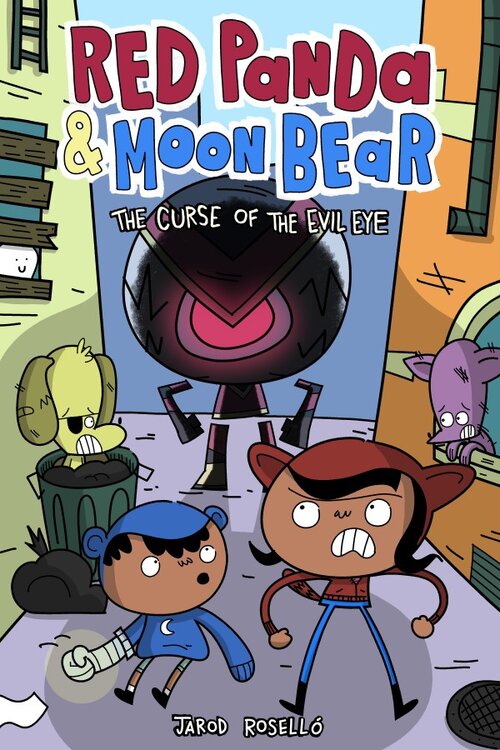

In his graphic novel Red Panda and Moon Bear (Top Shelf, 2019), Roselló strove to emulate the children’ storytelling style. His forthcoming book, Red Panda and Moon Bear (Book Two): The Curse of the Evil Eye, to be published by Top Shelf in January 2022, continues with this storytelling method.

“The whole premise of the book is a world in which things that don’t belong continue to appear, and so I just fold them into each other,” says Roselló.

The title characters in Red Panda and Moon Bear are Cuban American siblings who pull on their hoodies when night falls and head out to protect their neighborhood from whatever invaders come their way: Evil space alien dogs, nightmare monsters, even a mutant ice cream cone that comes to life.

“I wanted Red Panda and Moon Bear to be able to will this world into existence and into a kind of magic by saying it or thinking it or imagining it,” he says.

The sequel will continue the adventures of the title characters and explore their world, “sort of a hybrid of Miami and Tampa,” which Roselló says is a magical place with a deep history.

The kid-influenced storytelling style works particularly well with comics, which are already a fragmented medium, delivering stories in discrete panels, he says.

“It really seems that comics is built for those kinds of divergent movements in storytelling and narrative,” he says, “and that was the thing I learned most from kids, which is that they’re not afraid to have their stories go in all kinds of interesting directions. I think Dav Pilkey does this really well in his ‘Dog Man’ books, and I think that’s part of the reason why kids like the ‘Dog Man’ books: They map onto children’s narrative structure so well.”

Roselló did impose some narrative constraints for himself. “Early on, part of one of the rules I set for myself if was that if Red Panda or Moon Bear say or believe something about the world, it has to come true. So in chapter one, Red Panda thinks that the dogs might be shape-shifting monsters from another galaxy, and it turns out in Chapter 10 she was right,” says Roselló.

In another chapter, as the pair hunt for a nightmare monster, they discuss what it might look like. The monster they find is exactly like the one they pictured.

Despite Roselló’s playful approach, the world of Red Panda and Moon Bear is anything but random. The Miami/Tampa–like setting has older roots lying below the surface.

“It is a cultural borderlands town,” he says, “so it’s predominantly Latino, but the city’s culture has been stacked historically. So as you dig into the history of the town, you uncover what has been buried beneath it, which is its older Spanish and Cuban roots.”

There’s also a secret organization, the Institute for Anomalous Behavior, which lies under the town. In Book Two, Red Panda and Moon Bear dive in and start investigating it.

The decision to give both his main characters and their town a Cuban background was deliberate and partly political, Roselló says. Growing up in Miami, he drew winter scenes with snowy trees, although that was far from his own reality.

“Stories get colonized,” he says. “I think there are images that come to colonize what things look like, who gets to appear in stories, that sort of thing.”

Roselló wanted his story to reflect the kids and families he grew up with, but he didn’t want that to be the subject of the story. So Red Panda and Moon Bear call their parents Papi and Mami, the characters speak Spanish occasionally, and Roselló drops in other bits of Cuban culture without interrupting the narrative to explain or translate.

“I think that two Cuban American second-generation siblings should be allowed to just go out and fight monsters and not always have to reflect on the trials and tribulations of their family as immigrants coming to this country,” Roselló says. “There are so many stories that are doing that work. I think we’re at a place where it doesn’t always have to be the subject of it anymore, and I’m really grateful for that.”

While Red Panda and Moon Bear are not opposed to punching the occasional monster, annihilation is not their goal. “Destroying your enemy with power is the easy way out,” says Roselló.

Instead, the siblings learn to understand the monsters and make space for them. “Red Panda and Moon Bear don’t want a world free of monsters,” he says. “They want monsters in the world. That’s exciting. It’s fun. Sure, they could have vanquished the nightmare monster and been done with it, but what a better world to live in where there is a nightmare monster than where there isn’t a nightmare monster. I think part of the struggle is making space for everybody, finding ways in which we don’t need to evict these characters, but we can coexist.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!