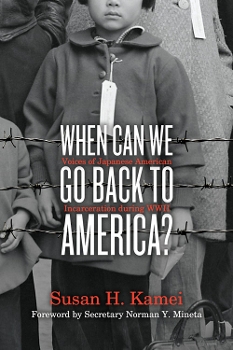

Interview: Susan H. Kamei on "When Can We Go Back to America?"

Author Susan H. Kamei discusses her YA narrative nonfiction work When Can We Go Back to America?: Voices of Japanese American Incarceration during WWII, and why it's so vital to acknowledge and understand this episode in U.S. history.

|

Photo by Rebecca Little |

Author Susan H. Kamei discusses her YA narrative nonfiction work When Can We Go Back to America?: Voices of Japanese American Incarceration during WWII (S. & S.), and why it's so vital to acknowledge and understand this episode in U.S. history.

You open the book with a quote by Emi Akiyama, who was incarcerated at eight years old:

“I’m always fearful that something like this might happen again. Not to me maybe, but just in the world. I see the neo-Nazis. That scares me to death. And these ultraconservatives...I think they could do something like this again. Not necessarily to me but to whoever will be vulnerable. I think I’m more fearful of racism since that whole experience.”

On top of detailing Executive Order 9066 and its aftermath, you also raise awareness of modern day atrocities and remind us where we come from so history won’t repeat itself. Can you talk more about the inclusion of Akiyama’s comments and why it was important to include in a narrative history resource?

From years of volunteer work, sharing the story of this dark episode in our nation’s history and its enduring tragic aftermath, I’ve learned that most people, especially those outside of the west coast, have no awareness that the incarceration took place. Those who might have heard some passing reference to it are generally unaware of the details and the scope of the travesty of justice, especially that two-thirds of those incarcerated were actually American citizens. So I think it’s important that as a society, we know about this history and acknowledge it.

In addition, it’s important that the incarceration be viewed not just as a footnote of World War II history, but as something relevant today. The factors that led to this constitutional breakdown are going on now. These factors include judicial and legislative deference to unchecked executive power asserted in issues of national security and targeting racial and other groups as the “enemy”—witness the sharp rise in violence against Asian Americans as the coronavirus has been referred to as “Kung flu” or the “Chinese virus.” I hope that the Akiyama quote at the top of the book helps set the stage for readers that as they learn about what happened 80 years ago, they also think about the ramifications for this history today and how they could process current events against this framework.

As shared in the Introduction, this book is personal to you since your parents and grandparents were incarcerated. You mention the silence that permeates the Japanese American community. Can you elaborate on where you think this silence stems from?

The incarcerated first-generation Issei and their second-generation American-born Nisei children were traumatized by their lives being destroyed by the forced removal and long-term detention, and by being viewed and treated as criminals when they had done nothing wrong. Upon their release from the camps, they faced overwhelming hatred and prejudice as they tried to return to their west coast homes and set about trying to rebuild their lives. A concept that is very fundamental to the Japanese culture is “shigata ga nai.” This phrase is loosely translated as “it can’t be helped,” meaning one must accept that which cannot be changed. There also is the concept of “gaman,” that one does not complain and endures hardship with strength—there is a cultural priority to “hang tough.” Because the false government narrative justified their incarceration as first a “military necessity” and later as “protective custody” for their own good, they realistically could not talk about their experiences without making it harder to be accepted back into White society. Instead, they concentrated on trying to move on to put the painful past behind them.

By the time my generation, the third-generation Sanseis, came along, we by and large could not communicate with our Issei grandparents, who generally spoke little or no English, and our Nisei parents also did not want to burden us with their trials. For all of these reasons and more, the Issei and Nisei suppressed their emotions and stories. My generation had no real ability to know, let alone understand, what our parents and grandparents had experienced. In one of the first virtual events I did, one viewer put into the chat that as a Sansei, she now has ways to talk about the incarceration with her grandchildren in a way she didn’t have before. In addition to educating the general public about the incarceration, I hope the book also gives those of us who are families of incarcerees a way to access our own family histories.

Much of what President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the U.S. government did to Japanese Americans during and post-WWII is pushed under the rug and glossed over in history classes. Why do you think people are ready and need to hear these stories now?

I think it’s more “better late than never” and “if not now, then when?” The question of reparations for descendants of enslaved people; the reexamination of racist names of sports, military bases, and civic institutions; and the acknowledgements of indigenous land are some other current examples of issues that are creating awareness of gaps in our historical understanding. I don’t know that people are so much as “ready” to hear these stories, but rather I hope they can hear them and see for themselves the patterns of exclusion, denial, and erasure, and would then be open to relating to history and the teaching of history in more inclusive ways.

I think it’s more “better late than never” and “if not now, then when?” The question of reparations for descendants of enslaved people; the reexamination of racist names of sports, military bases, and civic institutions; and the acknowledgements of indigenous land are some other current examples of issues that are creating awareness of gaps in our historical understanding. I don’t know that people are so much as “ready” to hear these stories, but rather I hope they can hear them and see for themselves the patterns of exclusion, denial, and erasure, and would then be open to relating to history and the teaching of history in more inclusive ways.

You refer to what happened to Japanese Americans as “Incarceration” as opposed to the often-used “Internment.” Why is this, and other uses of language, so important when writing and talking about this?

The government, and in particular the War Department and U.S. Army, purposefully used euphemistic terms as part of its justification for the military actions that carried out Executive Order 9066. The term “internment” specifically refers to the federal government’s ability to detain aliens who are suspected of espionage or sabotage against U.S. interests. The term “internment” could not and should not have been referred to the Nisei American citizens; by definition, the government could not “intern” a citizen. The government referred to the Nisei Americans as “non-aliens” to include them in the exclusion orders that removed them from the west coast, rather than acknowledge that these actions were being taken against U.S. citizens in violation of their constitutional rights. Therefore, organizations such as the Japanese American National Museum and Densho, and numerous scholars today consider the use of the term “internment” to be inaccurate and in support of the false government justification, preferring the word “incarceration,” which also more accurately conveys the connotation of imprisonment.

By way of example of other euphemistic terms, the word “evacuation” applies to removing individuals out of harm’s way, and not removing individuals who are considered to be the harm. The Army even referred to the first two detention facilities as “reception centers,” as if they were pleasant or hospitable places.

So much literature exists using the term “internment” and the incarcerees themselves used the government terms that I recognize it is not realistic to get completely away from the euphemistic vocabulary. Nevertheless, I think we should recognize the differences and be purposeful about using accurate terminology when possible.

Students study historical photos to analyze as primary sources. You mention that many of the photos depicted well-dressed smiling faces to allow the government to say that Japanese Americans were happy to be incarcerated. As a book rife with primary and secondary sources, can you share your research process and how cultural competency is so important when looking at and thinking about the present?

Regarding the analysis of photography, I include in my course at USC a session on understanding the images from the perspectives of those who took the photographs and the purposes for which the photos were taken. We can also question the absence or dearth of certain kinds of photos. For example, numerous first-hand accounts describe armed soldiers pointing guns or bayonets at them as they were taken from their homes, loaded onto buses and trains for transport to the detention facilities, or living within the barbed-wire confines. There are also reports of some soldiers abusing their power and treating the incarcerees harshly. However, the photos with soldiers instead show them with their guns at their sides and being solicitous, such as helping mothers by carrying their babies and escorting the elderly. I think this points to the importance of students and researchers continuously integrating information and “connecting the dots.”

Whenever possible, I cited primary sources, providing URLs for material that is digitally available, and when appropriate to the narrative, I included text of the primary sources in the body of the book. I also reviewed the material contained in previously published books on subtopics to determine the relevant secondary sources. In checking the citations in leading secondary sources, I discovered in a few cases that sources had been incorrectly cited (e.g., to wrong sources or that the source did not support the textual reference). In these cases, I identified the correct source and/or a primary source as the citation. For some events, multiple secondary sources presented conflicting or contradictory versions; in these situations, I conducted further research to reconcile the accounts or to determine which account was the most accurate. It was helpful—and meaningful—that I personally knew some of those included as contributor voices and many of the key figures, such as Mike Masaoka, Min Yasui, and the Nisei legislative leaders, which gave me confidence in selecting the passages that quote them. And some portions are my own “lived history,” such as growing up being told “shigata ga nai” and being personally involved in the redress campaign. I hope that as a result of my personal connection to this material that readers will come away with their own sense of connection to what they have read.

The quotes interspersed throughout the book at their appropriate historical moments and the further detailed and researched biographies at the end of the book give voice and pathos to what often feels like dry history. How did you find these testimonies and how did you decide where and when to use them within the text?

I was familiar with the testimonies that were submitted and presented at the hearings of the congressional commission, the collections of videoed oral histories by Densho, the Japanese American National Museum, the various Nisei veterans organizations, and the relatively few first-person books by Nisei incarcerees. I also examined sources such as transcripts of congressional hearings, digitized interagency correspondence and the Congressional Record, and articles in newspapers and other media.

The quotes were placed to propel and illustrate the historical narrative, so there was a certain chronology to them. The goal was to make the incarceration experience real and undeniable—that this really happened, that it happened to real people, and that we should and could care about the real impact that this had on them, and upon our society.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!