2018 School Spending Survey Report

How I Corrupted America's Youth

Getting angry letters is no laughing matter—and the same goes for censorship

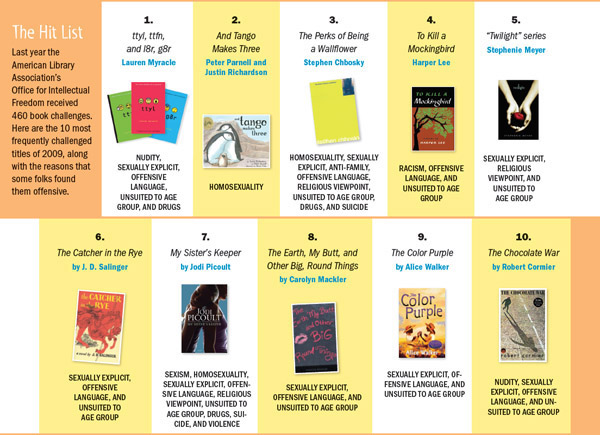

Recently, I received a message from a father in South Carolina... "Hello Dan: I double dog dare you to read this entire email and not dismiss it as some fringe, conservative wacko diatribe. My son is seven years old and brought your book (Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet) up to me and said, "Dad, this book has bad words in it." When I read it I was shocked at the level of depravity that spewed out of almost every thought of the characters in this book. You have propagated a literary abomination. Do you believe that all kids think at this depraved level? My seven-year-old was repulsed at how these characters were thinking and talking. With this kind of superficial, rude content it's no wonder that young people are loading up with guns and going into schools and shooting everyone. The first line in your book is "My name is A. J. and I hate school." There is no justification for feeding impressionable minds this kind of coarse, hateful thinking. At one point a girl comes up to A .J. and introduces herself and A. J's response is to call her an annoying girl and to say that he hates her. These are things that we should be teaching our children NOT to do, say, or think. You cannot believe that you can expose young minds to this level of depraved discourse and not have some of it be adopted by the reader. If you don't think these types of thoughts are depraved then you really are out of touch. I shared this with several teachers and parents and 100 percent were shocked. The popularity of your books is only an indication that parents are unaware of the content of your material. I have not met anyone that disagrees with me so far. The principal of my son's school agreed with me, and we are working to have your books banned from the school. I will also be contacting the school board at other schools and bringing this material to their attention. Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet is poison for young minds, and I will do everything in my power to get these books off the shelf. Your book changed my life because now I am going to pay to send my kid to private school to protect him from a society whose morals have been eroded to a level that this kind of acrimonious dribble would even be considered much less popular." Wow! I've received some angry letters, but this one beats 'em all. Here I am, thinking "My Weird School" is a goofy series that turns on reluctant readers, when in fact I'm poisoning young minds with my depraved, acrimonious dribble. Acrimonious dribble? My first reaction, I must confess, was to laugh. I mean, get a sense-of-humor transplant, buddy! These are humor books. Of all the problems facing the world today, this guy's biggest concern is "My Weird School"? Some of my fellow children's book authors thought the letter was hilarious. "Of course we all knew how depraved you were," Jon Scieszka told me. "We just didn't know you were this depraved." Gordon Korman responded, "I guess it starts with second graders who say they hate school, and before you know it, we're all speaking Russian." Being a typically insecure writer, my second reaction was to ask myself, did that parent have a legitimate gripe? Even if 99 percent of the letters I get are positive, is it possible that I'm actually hurting children with my books? I know (from other emails) that some parents tell their children "hate" is a bad word, almost as if it's an obscenity. Certainly, to have a character say, "I hate Jews" or "I hate Eskimos" would be wrong. But is it inappropriate for a character to hate asparagus? To hate Mondays? To hate cold weather? It's true that my main character, A. J., says he hates school and hates a girl in his class named Andrea. He's a mischievous little smart aleck, and that's the way kids like that talk. But readers of "My Weird School" know that A. J. is constantly being teased by his friends because he's secretly in love with Andrea. Little boys often show they like something by saying that they hate it. After thinking it over, I decided not to worry about kids reading the word "hate" in one of my books and going off to fill the world with hatred. I find it interesting that characters in my books have been physically attacked, kidnapped, locked in a closet, had baseball bats thrown at them, and have even been shot at, but not one parent has ever complained about violence. It's always about words. "Hate" and "butt" seem to be particularly offensive. Jane Yolen, whose novel Briar Rose (Tor, 1992) was burned on the steps of the Kansas City Board of Education because it features a gay character, told me, "If that parent thinks saying 'I hate school' is depraved, he is living on another planet." The author's responsibility Nearly all the complaints I receive inform me that it's my responsibility as an author to promote positive messages and moral lessons in my books. Honestly, that never even crossed my mind. I always thought it was the parent's responsibility to raise their children. My books are purely for entertainment. I don't put "lessons" in them, at least not intentionally. Frankly, I'm suspicious of authors or authority figures that want to teach my kids morality. Morality according to whom? My goal is to get kids excited about reading. In Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet (HarperCollins, 2008), I try to hook them with the first sentence ("My name is A. J. and I hate school."). A child who doesn't like school or reading will see that first sentence and, I hope, think "This book speaks to me. Maybe it will be different." If I've done my job, that child will open the book and become so captivated that two hours later he'll look up and not even realize he was reading. It's human nature to find conflict more interesting than harmony. If authors just wrote perfect little angel characters who never did or said anything negative, books would be boring and kids wouldn't want to read them. To hold a child's attention and create compelling stories, we write books in which characters of opposing personalities come into conflict. Sometimes they hate each other. Just like in the real world. Having characters that get angry with one another doesn't promote hatred. It reflects reality. Peg Kehret told me, "By including unethical characters, I feel I'm showing readers the bad consequences of such behavior." Peg also told me a woman tried to get her book Abduction! (Dutton, 2004) banned from every school in the district because it was too scary for her daughter. Bruce Coville, who has suffered more than his share of angry book banners, hits the nail on the head: "Somehow the idea seems to have gotten loose in the country that in addition to the rights of speech, religion, and the press we now have a new constitutional right: the right to never be offended by anything." How we respond OK, now that I've convinced myself that I'm not completely depraved, what next? Should authors respond when people send us angry letters? Not everyone agrees. Peg Kehret told me she would not have responded at all, and Lois Lowry says she responds to such letters politely, but "lengthy discourse on my part will not change their feelings." Personally, I can't help myself. When someone attacks me, I have to defend myself. I wrote back to the guy and said the beauty of America is the freedom to make our own decisions. We don't have just one person or one committee telling us how to think, what to believe, or what our kids should be allowed to read. Freedom of speech, I insisted, means freedom from censorship. It's fine for a parent to decide his child shouldn't read a particular book. But if that parent gets the book banned from a school, they are deciding what other parents' children may or may not read. That doesn't sound fair to me. It doesn't sound American either. I wouldn't want some other parent telling me what my daughter can read. As Bruce Coville puts it, "Withholding information is the essence of tyranny. Control of the flow of information is the tool of the dictatorship." In America, I continued, we get exposed to many different viewpoints. We may not like them all, but that's the price we pay to live in a democracy. The American way is to make up our own mind about what books our children should be able to read, and allow other parents to make up their own minds as well. Told him a thing or two, huh? It seemed like an airtight argument, one that would appeal to this gentleman's patriotism. I didn't expect to hear back from him. But I did, two days later. "You can't yell 'fire' in a crowded theater and you can't sell kiddy porn," he informed me. "That behavior is illegal. In some cases censorship is good." And here, I must admit, he's right. There are certain words and subjects that do not belong in a children's book. If a book is published with that material in it, somebody's got to decide how to handle it. And that somebody, I realize, is you. When a parent challenges a book in your library, the easy thing to do would be to take that book off the shelf. Avoid problems. But then the censors and book banners win. We end up with writers who are afraid to write, publishers who are afraid to publish, and children who are not challenged to use their minds. "All too often the prevailing desire in administrators is, 'Let there be no fuss,'" says Coville. "But fuss is part of the process, and to deny us our fusses is to deny us our freedom. The real heroes are the librarians and teachers who at no small risk to themselves refuse to lie down and play dead for censors." The challenge we face is this: people who want to ban books are so sure they're right, they can't imagine anybody could possibly think differently. They believe their judgment should be the standard for everyone. Not only must their child not see a book, but no child should be allowed to see it. (Man, I wish I had that kind of self-assurance. I'm never that sure I'm right.) "They are mini-dictators," says Coville, "and need to be resisted at every turn." Most reasonable librarians, I trust, will come down on the side of free speech over censorship and book banning. Most SLJ readers would not let a few angry, outspoken parents decide what all students should be allowed to read. I think I can speak for all authors when I say a big thank-you for the time and effort you put into carefully evaluating each challenged book and dealing with these unpleasant situations. Unfortunately, because of the Internet, the book-banning crowd now has a forum. They can (and do) go on the Web sites of Amazon, Borders, and Barnes & Noble, pull a few words out of context from a book, and tell the world that a silly book like Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet is responsible for school shootings. There's nothing I can do about it. Maybe I should just stop worrying and enjoy the free publicity authors get when one of our books is controversial. As Steve Swinburne, author of Wiff and Dirty George (Boyds Mills, 2010), told me, "Now you've got what every writer wants—a banned book! You lucky dog." Maybe Steve's right. Hey look, I just parlayed this thing into a big article for School Library Journal! Now if one of you nice librarians would just send a copy of this magazine to Oprah...

Recently, I received a message from a father in South Carolina... "Hello Dan: I double dog dare you to read this entire email and not dismiss it as some fringe, conservative wacko diatribe. My son is seven years old and brought your book (Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet) up to me and said, "Dad, this book has bad words in it." When I read it I was shocked at the level of depravity that spewed out of almost every thought of the characters in this book. You have propagated a literary abomination. Do you believe that all kids think at this depraved level? My seven-year-old was repulsed at how these characters were thinking and talking. With this kind of superficial, rude content it's no wonder that young people are loading up with guns and going into schools and shooting everyone. The first line in your book is "My name is A. J. and I hate school." There is no justification for feeding impressionable minds this kind of coarse, hateful thinking. At one point a girl comes up to A .J. and introduces herself and A. J's response is to call her an annoying girl and to say that he hates her. These are things that we should be teaching our children NOT to do, say, or think. You cannot believe that you can expose young minds to this level of depraved discourse and not have some of it be adopted by the reader. If you don't think these types of thoughts are depraved then you really are out of touch. I shared this with several teachers and parents and 100 percent were shocked. The popularity of your books is only an indication that parents are unaware of the content of your material. I have not met anyone that disagrees with me so far. The principal of my son's school agreed with me, and we are working to have your books banned from the school. I will also be contacting the school board at other schools and bringing this material to their attention. Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet is poison for young minds, and I will do everything in my power to get these books off the shelf. Your book changed my life because now I am going to pay to send my kid to private school to protect him from a society whose morals have been eroded to a level that this kind of acrimonious dribble would even be considered much less popular." Wow! I've received some angry letters, but this one beats 'em all. Here I am, thinking "My Weird School" is a goofy series that turns on reluctant readers, when in fact I'm poisoning young minds with my depraved, acrimonious dribble. Acrimonious dribble? My first reaction, I must confess, was to laugh. I mean, get a sense-of-humor transplant, buddy! These are humor books. Of all the problems facing the world today, this guy's biggest concern is "My Weird School"? Some of my fellow children's book authors thought the letter was hilarious. "Of course we all knew how depraved you were," Jon Scieszka told me. "We just didn't know you were this depraved." Gordon Korman responded, "I guess it starts with second graders who say they hate school, and before you know it, we're all speaking Russian." Being a typically insecure writer, my second reaction was to ask myself, did that parent have a legitimate gripe? Even if 99 percent of the letters I get are positive, is it possible that I'm actually hurting children with my books? I know (from other emails) that some parents tell their children "hate" is a bad word, almost as if it's an obscenity. Certainly, to have a character say, "I hate Jews" or "I hate Eskimos" would be wrong. But is it inappropriate for a character to hate asparagus? To hate Mondays? To hate cold weather? It's true that my main character, A. J., says he hates school and hates a girl in his class named Andrea. He's a mischievous little smart aleck, and that's the way kids like that talk. But readers of "My Weird School" know that A. J. is constantly being teased by his friends because he's secretly in love with Andrea. Little boys often show they like something by saying that they hate it. After thinking it over, I decided not to worry about kids reading the word "hate" in one of my books and going off to fill the world with hatred. I find it interesting that characters in my books have been physically attacked, kidnapped, locked in a closet, had baseball bats thrown at them, and have even been shot at, but not one parent has ever complained about violence. It's always about words. "Hate" and "butt" seem to be particularly offensive. Jane Yolen, whose novel Briar Rose (Tor, 1992) was burned on the steps of the Kansas City Board of Education because it features a gay character, told me, "If that parent thinks saying 'I hate school' is depraved, he is living on another planet." The author's responsibility Nearly all the complaints I receive inform me that it's my responsibility as an author to promote positive messages and moral lessons in my books. Honestly, that never even crossed my mind. I always thought it was the parent's responsibility to raise their children. My books are purely for entertainment. I don't put "lessons" in them, at least not intentionally. Frankly, I'm suspicious of authors or authority figures that want to teach my kids morality. Morality according to whom? My goal is to get kids excited about reading. In Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet (HarperCollins, 2008), I try to hook them with the first sentence ("My name is A. J. and I hate school."). A child who doesn't like school or reading will see that first sentence and, I hope, think "This book speaks to me. Maybe it will be different." If I've done my job, that child will open the book and become so captivated that two hours later he'll look up and not even realize he was reading. It's human nature to find conflict more interesting than harmony. If authors just wrote perfect little angel characters who never did or said anything negative, books would be boring and kids wouldn't want to read them. To hold a child's attention and create compelling stories, we write books in which characters of opposing personalities come into conflict. Sometimes they hate each other. Just like in the real world. Having characters that get angry with one another doesn't promote hatred. It reflects reality. Peg Kehret told me, "By including unethical characters, I feel I'm showing readers the bad consequences of such behavior." Peg also told me a woman tried to get her book Abduction! (Dutton, 2004) banned from every school in the district because it was too scary for her daughter. Bruce Coville, who has suffered more than his share of angry book banners, hits the nail on the head: "Somehow the idea seems to have gotten loose in the country that in addition to the rights of speech, religion, and the press we now have a new constitutional right: the right to never be offended by anything." How we respond OK, now that I've convinced myself that I'm not completely depraved, what next? Should authors respond when people send us angry letters? Not everyone agrees. Peg Kehret told me she would not have responded at all, and Lois Lowry says she responds to such letters politely, but "lengthy discourse on my part will not change their feelings." Personally, I can't help myself. When someone attacks me, I have to defend myself. I wrote back to the guy and said the beauty of America is the freedom to make our own decisions. We don't have just one person or one committee telling us how to think, what to believe, or what our kids should be allowed to read. Freedom of speech, I insisted, means freedom from censorship. It's fine for a parent to decide his child shouldn't read a particular book. But if that parent gets the book banned from a school, they are deciding what other parents' children may or may not read. That doesn't sound fair to me. It doesn't sound American either. I wouldn't want some other parent telling me what my daughter can read. As Bruce Coville puts it, "Withholding information is the essence of tyranny. Control of the flow of information is the tool of the dictatorship." In America, I continued, we get exposed to many different viewpoints. We may not like them all, but that's the price we pay to live in a democracy. The American way is to make up our own mind about what books our children should be able to read, and allow other parents to make up their own minds as well. Told him a thing or two, huh? It seemed like an airtight argument, one that would appeal to this gentleman's patriotism. I didn't expect to hear back from him. But I did, two days later. "You can't yell 'fire' in a crowded theater and you can't sell kiddy porn," he informed me. "That behavior is illegal. In some cases censorship is good." And here, I must admit, he's right. There are certain words and subjects that do not belong in a children's book. If a book is published with that material in it, somebody's got to decide how to handle it. And that somebody, I realize, is you. When a parent challenges a book in your library, the easy thing to do would be to take that book off the shelf. Avoid problems. But then the censors and book banners win. We end up with writers who are afraid to write, publishers who are afraid to publish, and children who are not challenged to use their minds. "All too often the prevailing desire in administrators is, 'Let there be no fuss,'" says Coville. "But fuss is part of the process, and to deny us our fusses is to deny us our freedom. The real heroes are the librarians and teachers who at no small risk to themselves refuse to lie down and play dead for censors." The challenge we face is this: people who want to ban books are so sure they're right, they can't imagine anybody could possibly think differently. They believe their judgment should be the standard for everyone. Not only must their child not see a book, but no child should be allowed to see it. (Man, I wish I had that kind of self-assurance. I'm never that sure I'm right.) "They are mini-dictators," says Coville, "and need to be resisted at every turn." Most reasonable librarians, I trust, will come down on the side of free speech over censorship and book banning. Most SLJ readers would not let a few angry, outspoken parents decide what all students should be allowed to read. I think I can speak for all authors when I say a big thank-you for the time and effort you put into carefully evaluating each challenged book and dealing with these unpleasant situations. Unfortunately, because of the Internet, the book-banning crowd now has a forum. They can (and do) go on the Web sites of Amazon, Borders, and Barnes & Noble, pull a few words out of context from a book, and tell the world that a silly book like Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet is responsible for school shootings. There's nothing I can do about it. Maybe I should just stop worrying and enjoy the free publicity authors get when one of our books is controversial. As Steve Swinburne, author of Wiff and Dirty George (Boyds Mills, 2010), told me, "Now you've got what every writer wants—a banned book! You lucky dog." Maybe Steve's right. Hey look, I just parlayed this thing into a big article for School Library Journal! Now if one of you nice librarians would just send a copy of this magazine to Oprah... Dan Gutman (dangut@comcast.net) is the author of the "My Weird School" series and many other books for young readers.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!