Three School Library-Based Summer Learning Programs

Check out these different models for school librarian-led summer learning initiatives, with or without grants and public library partners.

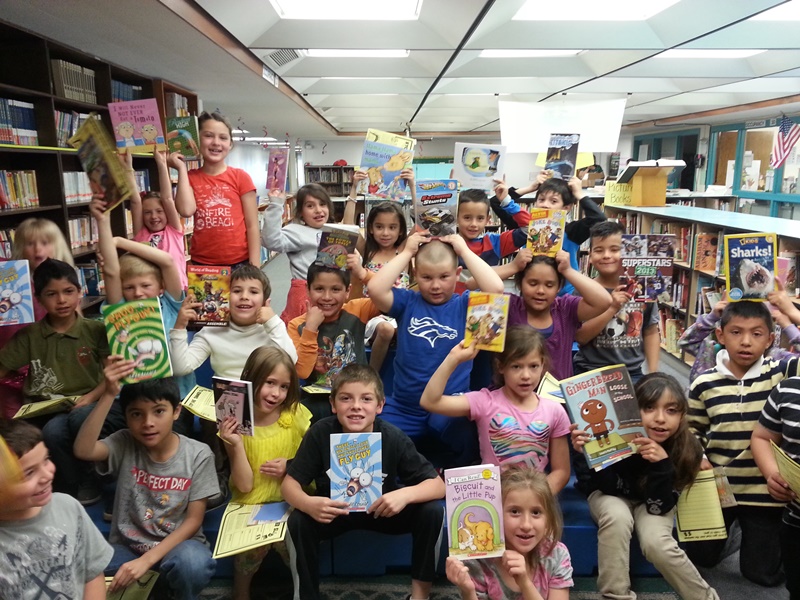

Summer learning—and fun—at a school library in Boise, ID.

Summer learning programs come in all shapes and sizes, depending on budget, location, demographics, and more. What works for one program might not be effective even in a nearby school. Here are three examples that illustrate different approaches.Leveraging Location in Virginia

Katie Cerqua

There are 55 schools and nine public libraries in Virginia Beach, VA. So when Katie Cerqua, a 2016 Library Journal Mover & Shaker who is the youth and family services manager for the Virginia Beach Public Library (VBPL), was deciding on the best place for summer learning programs, it was a no-brainer. The schools. That’s because more schools are within walking distance of students’ homes than libraries, Cerqua says. The locations make a big difference for students whose parents can’t provide transportation. Cerqua and VBPL staffers, working with teachers and school librarians, have run programs out of Title 1 schools in Virginia Beach for the past three summers. The initiative started when Cerqua met the coordinator for Title 1 facilities as part of a team called Growth Smart Virginia Beach, which included city agency employees, educators, and representatives of nonprofits working with children from birth to age eight. The principals of the 13 participating Title 1 schools determine which kids will be targeted to participate in the summer program, either due to their reading scores or other factors indicating that have a higher risk of extensive summer learning loss. Cerqua expects between 900 and 1,000 children this summer, almost 50 percent more than last year. The programs her staff runs generally run 45 minutes to one hour, and if they are crowded, students come in shifts. “We go out to school buildings once a week,” Cerqua says, while school staff work three days. Each day, they read books aloud on a designated topic and do a related hands-on activity. This summer, Cerqua’s adding a journaling component, along with activities ranging from creating art on solar powered paper and writing a related poem to building a robot. Whatever the day’s theme and activity, the most important aspect is that the students have fun: “The schools are adamant that it is not summer school.” Cerqua says that these strategies have shown a 61–73 percent success rate meaning that the participants either maintained or improved their reading skills from one year to the next. “[VBPL] is strategically making the choice to focus a lot of our resources on this program,” she adds. However, that commitment means fewer staff-run programs at the library during the summer. To compensate, VBPL used grants from the local Friends of the Library organization to bring guests with child appeal to the library. Last year, those included furry friends from a petting zoo and clowns.IMLS-funded “book fair” programs in Idaho

Selecting summer reading at a Boise school library.

This will be the third summer that elementary schools serving low-income students in Boise, ID, will stay open. This year, each of the four participating schools will receive a stipend of $1,500 from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), administered by the Idaho Commission for Libraries (ICfL), to keep their libraries open two days a week for two and a half months. Some stay open in the evening to accommodate busy schedules. “We offer grant programs and training that focuses on summer reading and early literacy programs,” says Stephanie Bailey-White, project coordinator for the Read to Me early literacy initiative at the ICfL, which receives IMLS funding to reach underserved children. “We’ve focused a lot on summer slide in the last five to 10 years.” She adds, “It started with programs to focus on collaborations between schools and libraries—getting principals and teachers involved, and tracking participation more closely.” The schools are participating in a “book fair model” program, in which kids in kindergarten through second grade each choose 10 books from a selection provided by ICfL to take home. School librarians are on hand to help them find ones they like. The children are encouraged to return the books when they’re done and pick replacements, but they aren’t penalized if they don’t bring them back. Bailey-White also strives to reach parents. The ICfL has a presence at school parent-teacher conferences in the spring and distributes brochures about summer reading programs in English and Spanish. It also created public service announcements for radio programs, boosting attendance from the first summer to the second. Continued growth is expected this summer. “The [schools] we’re working with now are pretty effective. They’re reaching about 20–40 percent, with really good principal participation,” says Bailey-White. Some 20 percent of kids from very low-income schools participate, she adds, and work is underway to reach the other 80 percent, with strategies such as automated reminder calls to parents and mailing books to homes during July to show that the school libraries are open. The organization also sponsors costumed character visits and activities. “We’re trying everything we can to reach children and parents to get those numbers up,” she says, While the data has not been fully interpreted, she believes that her book fair approach is making a difference in how much kids read at home.An Oregon school strikes out on its own

Summer STEM activities at Four Corners Elementary School in Salem, OR.

In Salem, OR, Katrina Axtell, librarian at Four Corners Elementary School, has created a summer program without a public library’s support. Axtell keeps her Title 1 school library open two days a week for four hours a day to pursue STEM activities, while also focusing on maintaining literacy. “We take the opportunity to add in the sciences,” she says. Axtell created the program with the support of the school’s administration and staff. “We’re not considered in our public library’s domain,” since the school is just beyond the boundary of the area served by the library, she explains, and the primarily low-income families in the school district must pay $60 for a public library card. Axtell’s budget of approximately $6,000 for 10 weeks of programming covers staffing, supplies, and, last year, a presenter from the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry. While Axtell is confident that the program mitigates summer slide, she admits that it might attract children who would lose less knowledge over the break anyway. “The students who come are considered our on-track students,” she says. “We target when we’re recruiting and send out letters to kids in the intensive zone, [but] the kids who are there are the students whose families read at home. It’s hard to collect data proving that these students would have lost knowledge and skills [otherwise].” About 150 kids participated in 2014, Axtell says, and approximately 80 last year—a decline that could result from practical impediments rather than waning interest, she believes. “Transportation is a real missing link for students who need it the most,” she notes, adding that when school is out, school bus service ends. Working without a public library partnership, Axtell remains committed to whoever shows

While Axtell is confident that the program mitigates summer slide, she admits that it might attract children who would lose less knowledge over the break anyway. “The students who come are considered our on-track students,” she says. “We target when we’re recruiting and send out letters to kids in the intensive zone, [but] the kids who are there are the students whose families read at home. It’s hard to collect data proving that these students would have lost knowledge and skills [otherwise].” About 150 kids participated in 2014, Axtell says, and approximately 80 last year—a decline that could result from practical impediments rather than waning interest, she believes. “Transportation is a real missing link for students who need it the most,” she notes, adding that when school is out, school bus service ends. Working without a public library partnership, Axtell remains committed to whoever shows  up. “Even just coming for an hour a week has a significant impact on summer learning loss, so I don’t want to turn them away or make them feel like they have to be there the whole four hours.” “Because the children are electing to come, having activities that spark curiosity and a love of learning gets you a level of fascination that you might not get during the school year,” Axtell says. “We have to give them a reason to keep coming back, so it inspires [the staff] to be more creative.”

up. “Even just coming for an hour a week has a significant impact on summer learning loss, so I don’t want to turn them away or make them feel like they have to be there the whole four hours.” “Because the children are electing to come, having activities that spark curiosity and a love of learning gets you a level of fascination that you might not get during the school year,” Axtell says. “We have to give them a reason to keep coming back, so it inspires [the staff] to be more creative.” Carly Okyle is a Carly Okyle is a writer at Entrepreneur.com. Her work has appeared in School Library Journal, Time.com, and YourTango.com, among other publications.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Scot Felderman

Kudos to the individuals and organizations for their work. However, what is most striking is the limited scale, scope and funding for this work. In my school district 60% of 3rd to 8th grade students read at the "well below proficient" level. We need greater rigor, intensity and resources if we are going to make a real difference for kids at greatest risk.Posted : May 11, 2016 10:35