Graphic Novels Offer Windows, Mirrors on Mental Health

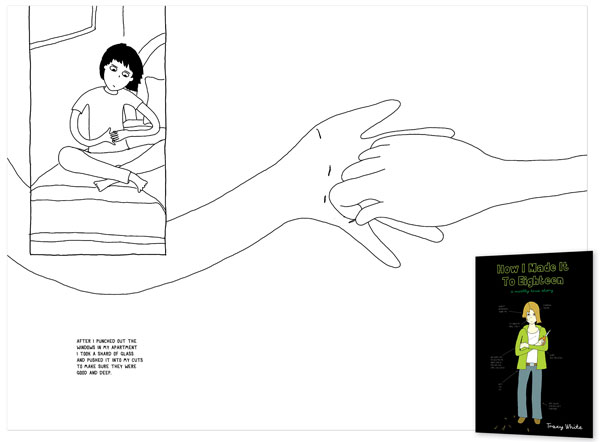

How I Made It to Eighteen by Tracy White.

Graphic novels are a powerful tool for portraying mental illness for two reasons: they are graphic, and they are novels. As a visual medium, the genre can convey the emotional perspective of mental illness and the distortions of reality that sometimes occur, more effectively than words alone. Also, there’s the intrinsic appeal of the format. “Graphic novels tell a story,” says Matthew Noe, library fellow at the Lamar Soutter Library at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester, MA, and a graphic medicine specialist at the National Network of Libraries of Medicine, New England Region. “If you can build information into a narrative with characters that people care about, they are more likely to connect with it.”

Graphic novels are a powerful tool for portraying mental illness for two reasons: they are graphic, and they are novels. As a visual medium, the genre can convey the emotional perspective of mental illness and the distortions of reality that sometimes occur, more effectively than words alone. Also, there’s the intrinsic appeal of the format. “Graphic novels tell a story,” says Matthew Noe, library fellow at the Lamar Soutter Library at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester, MA, and a graphic medicine specialist at the National Network of Libraries of Medicine, New England Region. “If you can build information into a narrative with characters that people care about, they are more likely to connect with it.”

That’s already happening with prose novels such as John Green’s Turtles All the Way Down, in which the main character has obsessive-compulsive disorder. “I feel like just within the past few years, there are a lot more YA novels coming out where mental health issues are addressed a little more explicitly or just considered part of the natural landscape of one of the characters or affecting characters and how they interact with the world,” says Gregory Taylor, a teacher librarian at Hillside Junior High School in Boise, ID.

At present, the number of graphic novels that deal with mental health is relatively small—and available titles appropriate for teens are fewer still—but that is likely to change as the medium grows and a new cohort of creators, who grew up at a time of unprecedented openness about mental illness, comes into maturity. Already this small body of work includes some powerful books that could only work in this format.

While students don’t ask him for books specifically about mental health, Taylor says, many request novels in which the characters are in trouble or struggling. “Especially with adolescents, it may not be on their radar that that’s what they are interested in,” he says. “Even if they are, they don’t know how to ask for it in those terms. They just know they like those kinds of stories or they like characters who are grappling with those sorts of things.”

Jennifer Jenks, MD, a psychiatrist in Ann Arbor, MI, who treats children, adolescents, and adults, sees the storytelling aspect of graphic novels as key. “It is a way of making people who struggle with mental health issues more accessible and more real,” she says. “Conveying this in the packaging of a graphic novel could be a very effective way of reaching kids. I know that teenagers often find it difficult to voice their own feelings. When I do therapy and say things like, ‘Some kids tell me that they feel jealous that their father is dating someone new,’ they may be able to access thoughts and feelings true to them that they either weren’t aware of or were having trouble sharing. In that vein, I could see a graphic novel being a helpful inroad to helping a teen tap into thoughts or feelings that felt too risky to experience on their own.”

Here’s a look at some graphic novels that tackle aspects of mental illness.

Lighter Than My Shadow

by Katie Green

Eating disorders

Katie Green’s Lighter Than My Shadow (Lion Forge, 2017) is a powerful memoir of anorexia, disordered eating, and sexual abuse. Green’s story takes herself from a child who was a picky eater through repeated bouts with anorexia and rigid eating habits, which are exacerbated by bullying at school and her own low self-esteem. Some of her therapists and doctors are clueless, while others are fooled by her calculated answers. Indeed, Green dupes many of the people around her, but not her readers—she draws her disorder as a black, scribbly cloud that sometimes hangs over her head and consumes her completely. Even when she appears to be doing well, the darkness is often hovering nearby. Finally Green goes to an “alternative therapist” who encourages her to rebel against her parents, and she begins to feel better, until she realizes that he has been sexually abusing her under the guise of therapy. Tortured by guilt, flashbacks, and feelings of worthlessness, Green attempts suicide, but when she finally pursues the art career she has always wanted and finds a therapist who understands her feelings, she begins to recover.

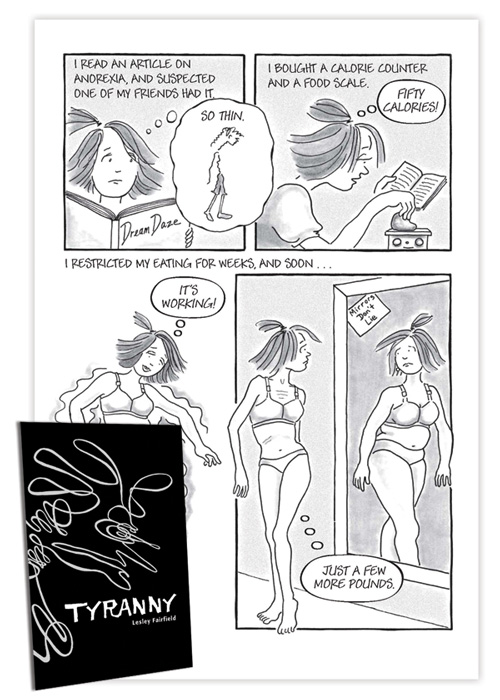

Anna, the central character in Tyranny by Lesley Fairfield, contends with anorexia.

It should be noted that Green’s depictions of sexual abuse are fairly explicit; nonetheless, she wrote Lighter Than My Shadow in part for teens. “I would love 17-year-olds to read it,” she said in my interview with her in May 2017. “I don’t blame myself for the abuse that happened to me, but I know that if I had a better understanding of what abuse is or looks like, it might have been stopped earlier. If teenagers are reading this kind of story, then hopefully they will understand it better.”

Tyranny (Tundra, 2009), by Lesley Fairfield, is another look at the same topic. This fictional story of a young woman with anorexia and bulimia uses a skeletal squiggle to represent the negative thoughts—the “tyranny”—that compel her to try to be thin. Anna, the heroine, struggles with her disorder and relapses before going into a residential treatment facility and finally gets well. Along the way, Fairfield depicts Anna’s distorted self-image, comparing her real body to what she sees in the mirror, and brings in other characters to show different aspects of the disorder. Although the subject is very serious—one character dies of the disease—Fairfield’s light, cartoony style keeps the book from ever feeling too heavy. (Note: Some nonsexual nudity.)

Both of these stories use the graphic medium to reveal the distortions in body image that come with eating disorders—in the case of Tyranny, Fairfield visualizes both the reality of Anna’s body and the inaccurate view she sees in the mirror. In Lighter Than My Shadow, Green imagines her belly bulging every time she eats. Meanwhile, she also envisions herself getting lighter and disappearing into a wisp of smoke as she loses weight.

Depression and anxiety

Tracy White’s subtitle for How I Made It to Eighteen (Roaring Brook, 2010) is “A Mostly True Story,” because she fictionalized some details of her life in her account of the time she spent in a psychiatric hospital recovering from depression. What is true is that White, like her character Stacy Black, suffered from depression, abused drugs, and entered a psychiatric hospital after punching out a window. Although she genuinely wants to get well, Stacy is hostile to her therapist and withholds the fact that she is bulimic. It is only after she admits this that her recovery can begin.

White uses several formats to tell her story: Each chapter of the book begins with accounts by four of Stacy’s friends about how they see a particular aspect of her disorder or her personality, followed by notes from the medical staff and a sequence about her life in the hospital.

Allie Brosh’s two online comics, Adventures in Depression and Depression Part Two, chronicle her experience with unvarnished honesty and offbeat humor. Although the second comic ends on a hopeful note, Brosh’s comic applies greater focus to the experience of depression than recovery. These two comics, along with other funny and insightful comics about identity, frustration with a world that doesn’t bend to her will, and the stupidity of her two dogs, are compiled in the book Hyperbole and a Half (Touchstone, 2013), which is also the title of her blog.

Terian Koscik talks to readers in a friendly, unthreatening voice in When Anxiety Attacks (Singing Dragon, 2015), a 32-page comic about seeing a therapist to deal with her anxiety and panic attacks. Koscik narrates her story matter-of-factly and recounts how her therapist put her at ease and helped her to rethink some of the patterns that were causing her anxiety to build. This comic is a good introduction to therapy and presents some simple techniques readers can use to manage anxiety.

Elaine M. Will uses surreal imagery in her novel, Look Straight Ahead.

Breaking with reality

In Look Straight Ahead (Alternative Comics, 2013), Elaine M. Will draws the world of her 17-year-old protagonist, Jeremy, in black and white—except when he is hallucinating. Even when things are relatively normal, Will makes powerful use of the graphic novel medium, with Jeremy’s world disintegrating into abstract planes and puzzle pieces as he tries to cope with bullies at school, his authoritarian father, and his own constant inner monologue of self-loathing. Things come to a head—and the story breaks into full color—when he has visions, believing he is at one with the universe and that God has a special plan for him. This quickly lands him in the hospital, where medication makes the hallucinations disappear but also drain his spirit, leaving him feeling sluggish and numb. He tosses the meds, but winds up with a terrifying companion, a black dog-like creature who taunts him, urging him toward despair and finally suicide. In the end, Jeremy literally conquers his demon, and, with help from his family and an understanding therapist, embarks on the road to recovery. In the last few pages, readers see him enjoying life as a well-adjusted adult. For Jeremy, it is art as much as any other treatment that helps him recover from his illness.

Making good choices

In terms of choosing graphic novels about mental health for a teen collection, Jenks says, “The best advice I could offer would be to consider the overall tone of the graphic novel—not necessarily to censor based on content, but to consider what the experience of adolescent readers would be. It would be helpful if graphic novels had a message of recovery (but not in a preachy, ‘After School Special’—and I say this totally dating myself!—way) as opposed to glamorizing concerning behaviors, like self-harm, suicide, and eating disorders.”

While students may self-diagnose after reading a book, Jenks says, “I wouldn’t be overly concerned that graphic novels would make kids diagnose themselves. In fact, I would think that seeing mental illness (anorexia, depression, psychosis) through the eyes of a fictitious character would give a kid a better sense of ‘that sounds like me’ than a list of symptoms that they might find on Wikipedia.”

At the same time, she says, it can be very empowering for patients to see someone like themselves in the pages of a book. “While there is the risk of kids seeing characters with mental illness and taking it on,” she says, “there could be real benefits to people who have true mental illness who see the same characters and feel some hope, or at least some shared experience.”

When choosing books about mental health, graphic novels or otherwise, for a teen audience, Anita Cellucci, a library teacher at Westborough (MA) High School and a 2016 finalist for School Librarian of the Year, says, “It’s important to me that the books list their sources. Also important is that the book has solid reviews and shows mental health as it would another illness (such as cancer) and doesn’t make the person at fault, a victim, or without a support system. I think this is essential in YA fiction—that the character who is experiencing mental health challenges has clinicians and other supports as part of their treatment.”

For Taylor, relatability is important: “Stories that kids can identify with, even if they are not identifying with the specifics of what the story is about” is what he looks for. Referring to the notion that books can be mirrors, reflecting readers’ own experiences, or windows that help them understand the experiences of others, he says, “Especially with young teenagers, I feel like they need to find a mirror in a story first, and then that opens them up to the windows more.” In the graphic novel realm, he cites El Deafo, Cece Bell’s memoir of growing up as a deaf child, as an example of a book that helps readers gain new insights into another’s experiences. “We need more of those about the autism experience or anxiety issues,” he says. “Somebody needs to do that book.”

Recommended Reading

How I Made It to Eighteen: A Mostly True Story, by Tracy White. Roaring Brook. 2010. Gr 9 Up—This semi-autobiographical graphic novel set in a psychiatric hospital features Stacy Black, a rebellious patient who conceals the fact that she is bulimic until the very end. The story is told in a series of vignettes, and Stacy and her real problems slowly come into focus. Lighter Than My Shadow, by Katie Green. Lion Forge. 2017. Gr 10 Up—A perfectionist as a child, Green began controlling her eating and ended up losing control. Therapy left her with as many questions as answers, and then she was sexually abused by a therapist. This book is long and at times difficult, but it’s also a realistic view of the ups and downs of recovery. Look Straight Ahead, by Elaine M. Will. Cuckoo’s Nest Pr. 2013. Gr 10 Up—Will’s art veers between realistic and surrealistic in this story of a teenager who faces bullies at school and his own self-loathing inner monologue at home—and has a psychotic breakdown as a result. Piper the Porcupine: A Tale of Autism, by Ilsa Kasmar. Knotted Road Pr. 2016. Gr 3 Up—Piper, a porcupine, doesn’t like to be touched and occasionally freaks out, but she loves drawing in her notebook. When her classmates see her artistic talent, the attention unnerves Piper, but her teacher responds in a kind and thoughtful way. Sobriety: A Graphic Novel, by Daniel Maurer. Illus. by Spencer Amundson. Hazelden Publishing. 2014. Gr 9 Up—Maurer, who was in recovery for opioid addiction, uses storytelling to demystify the 12-step process of recovery. The story features Mauer as narrator and the words of participants in a 12-step program, each of whom has a different story to tell. Sweaty Palms: The Anthology About Anxiety, ed. by Liz Enright and Sage Coffey. Self-published. 2016. gumroad.com/sweatypalms Gr 10 Up—A collection of 50 short autobiographical comics detailing the creators’ experiences with—and recovery from—panic attacks, generalized anxiety, phone phobia, social phobias, agoraphobia, and other conditions up and down the anxiety spectrum. Tyranny, by Lesley Fairfield. Tundra. 2009. Gr 9 Up—This story of anorexia personalizes the disease as a black scribble that taunts the lead character, Anna, telling her she is fat. Fairfield depicts what Anna really looks like and the distorted image she sees in the mirror. This story considers the societal pressures that can exacerbate the disease. The Wendy Project, by Melissa Jane Osborne, illus. by Veronica Fish. Super Genius. 2017. Gr 7 Up—When the car Wendy is driving plunges off a bridge and her brother disappears, everyone assumes he has drowned—but Wendy is sure she saw him fly away. She tells her story in a journal given to her by her therapist as she struggles to work through the effects of her trauma. When Anxiety Attacks, by Terian Koscik. Singing Dragon. 2015. Gr 7 Up—With a loose, casual drawing style and cheeky humor, Koscik explains what it’s like to be anxious and undergo therapy. Through conversations with her therapist, the author offers some basic techniques for addressing anxiety.

How I Made It to Eighteen: A Mostly True Story, by Tracy White. Roaring Brook. 2010. Gr 9 Up—This semi-autobiographical graphic novel set in a psychiatric hospital features Stacy Black, a rebellious patient who conceals the fact that she is bulimic until the very end. The story is told in a series of vignettes, and Stacy and her real problems slowly come into focus. Lighter Than My Shadow, by Katie Green. Lion Forge. 2017. Gr 10 Up—A perfectionist as a child, Green began controlling her eating and ended up losing control. Therapy left her with as many questions as answers, and then she was sexually abused by a therapist. This book is long and at times difficult, but it’s also a realistic view of the ups and downs of recovery. Look Straight Ahead, by Elaine M. Will. Cuckoo’s Nest Pr. 2013. Gr 10 Up—Will’s art veers between realistic and surrealistic in this story of a teenager who faces bullies at school and his own self-loathing inner monologue at home—and has a psychotic breakdown as a result. Piper the Porcupine: A Tale of Autism, by Ilsa Kasmar. Knotted Road Pr. 2016. Gr 3 Up—Piper, a porcupine, doesn’t like to be touched and occasionally freaks out, but she loves drawing in her notebook. When her classmates see her artistic talent, the attention unnerves Piper, but her teacher responds in a kind and thoughtful way. Sobriety: A Graphic Novel, by Daniel Maurer. Illus. by Spencer Amundson. Hazelden Publishing. 2014. Gr 9 Up—Maurer, who was in recovery for opioid addiction, uses storytelling to demystify the 12-step process of recovery. The story features Mauer as narrator and the words of participants in a 12-step program, each of whom has a different story to tell. Sweaty Palms: The Anthology About Anxiety, ed. by Liz Enright and Sage Coffey. Self-published. 2016. gumroad.com/sweatypalms Gr 10 Up—A collection of 50 short autobiographical comics detailing the creators’ experiences with—and recovery from—panic attacks, generalized anxiety, phone phobia, social phobias, agoraphobia, and other conditions up and down the anxiety spectrum. Tyranny, by Lesley Fairfield. Tundra. 2009. Gr 9 Up—This story of anorexia personalizes the disease as a black scribble that taunts the lead character, Anna, telling her she is fat. Fairfield depicts what Anna really looks like and the distorted image she sees in the mirror. This story considers the societal pressures that can exacerbate the disease. The Wendy Project, by Melissa Jane Osborne, illus. by Veronica Fish. Super Genius. 2017. Gr 7 Up—When the car Wendy is driving plunges off a bridge and her brother disappears, everyone assumes he has drowned—but Wendy is sure she saw him fly away. She tells her story in a journal given to her by her therapist as she struggles to work through the effects of her trauma. When Anxiety Attacks, by Terian Koscik. Singing Dragon. 2015. Gr 7 Up—With a loose, casual drawing style and cheeky humor, Koscik explains what it’s like to be anxious and undergo therapy. Through conversations with her therapist, the author offers some basic techniques for addressing anxiety. On the Web

Adventures in Depression, by Allie Brosh Depression Part Two, by Allie Brosh

In these lengthy comics/prose blog posts, Brosh recounts her own depression and the beginnings of her recovery.Kevin Budnik kevinbudnik.com Budnik describes his struggle with anxiety and an eating disorder in diary comics posted on his website.

Mindful Drinking, by Cathy Leamy Written for adults (who can legally drink), this comic delivers a serious message with a big dose of humor—which could get teens thinking about their own habits.

MPD for You and Me, by LB Lee

Questions, by LB Lee Several of Lee’s personalities (alters) discuss multiple personality disorder—and explain why it’s a misnomer. Lee offers a whole page of free comics and articles about multiplicity (http://ow.ly/uI9j30hSYpZ).Today..., by MysticEden A diary comic chronicling the daily life of someone with multiple personalities.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Martha Cornog

Here are some more graphic novels about mental illness, primarily for adults but many can go younger. These titles were compiled in late 2015: https://reviews.libraryjournal.com/2015/12/books/graphic-novels/deconnick-co-gaiman-mizuki-morrison-smithwinet-and-others-graphic-novels-reviews-january-1-2016/Posted : Mar 08, 2018 04:38